Why the U.S. hasn’t returned to the Moon and what’s next

Explore why the U.S. hasn’t returned to the moon and discover new lunar missions like Artemis aiming to land humans on the moon again.

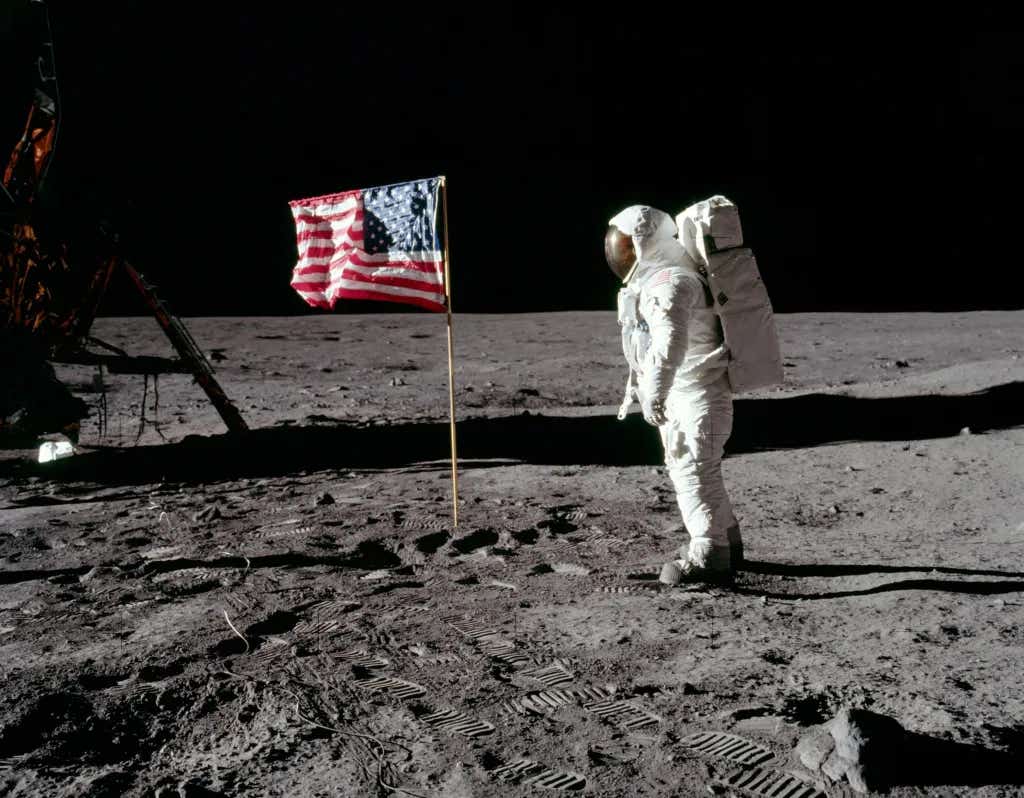

In July 1969, the United States achieved a monumental feat in human history when Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin became the first humans to set foot on the lunar surface during NASA’s Apollo 11 mission. (CREDIT: NASA)

In July 1969, the United States achieved a monumental feat in human history when Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin became the first humans to set foot on the lunar surface during NASA's Apollo 11 mission. The Apollo program, driven by intense Cold War competition with the Soviet Union, epitomized technological ingenuity, political will, and substantial financial investment.

Over the course of six successful missions between 1969 and 1972, NASA landed 12 astronauts on the moon, conducting extensive scientific experiments and collecting valuable lunar samples. Yet, despite this remarkable success, no human has returned to the moon since 1972. Understanding why requires examining a confluence of technological, political, financial, and international factors.

The Apollo program’s roots lie in President John F. Kennedy’s bold 1961 proclamation to land a man on the moon and return him safely to Earth before the decade’s end. The urgency stemmed from the Soviet Union’s early dominance in space exploration, including Yuri Gagarin’s historic orbit of Earth in 1961.

Apollo became a matter of national pride and geopolitical strategy, with Congress approving massive funding to ensure its success. The program cost an estimated $25.4 billion—over $150 billion in today’s dollars—and involved over 400,000 workers across various industries.

By the time Apollo 17 concluded in December 1972, public interest and political support for lunar missions had waned. The Vietnam War, economic challenges, and changing national priorities redirected federal resources. NASA shifted its focus to other programs, such as the Space Shuttle, which promised reusable spacecraft and lower costs. The moon became a secondary objective as attention turned to Earth orbit and interplanetary exploration.

Technological stagnation also contributed to the lack of lunar return missions. The Saturn V rocket, the workhorse of the Apollo program, was retired after Apollo 17, leaving NASA without a launch vehicle capable of carrying astronauts to the moon. While the Space Shuttle was a technological marvel, it was designed for low Earth orbit operations, not deep space missions. Developing a new lunar-capable system would require years of investment and innovation.

Political will has also fluctuated over the decades. While presidents from George H.W. Bush to Donald Trump have proposed ambitious lunar programs, these initiatives often lacked sustained bipartisan support and funding from Congress.

For instance, the Constellation program, initiated under President George W. Bush, aimed to return astronauts to the moon by 2020 but was canceled in 2010 due to budget overruns and delays. President Trump’s Artemis program has shown promise, but it too faces challenges in securing consistent funding and maintaining momentum across changing administrations.

Related Stories

Financial constraints remain a significant hurdle. Lunar missions are extraordinarily expensive, requiring billions of dollars for spacecraft development, infrastructure, and operational costs. Competing priorities within NASA—such as the International Space Station (ISS), Mars exploration, and scientific research—further strain the budget.

Additionally, shifts in public opinion and political focus on immediate concerns, like climate change and domestic issues, have made it difficult to justify the expense of lunar exploration.

International competition has also evolved. While the U.S.-Soviet space race defined the Apollo era, the modern landscape includes new players such as China, India, and private companies. China’s Chang’e program has achieved significant milestones, including landing rovers on the moon’s far side and returning lunar samples to Earth.

India’s Chandrayaan missions have expanded our understanding of lunar geology, while private companies like SpaceX and Blue Origin have introduced new technologies and capabilities that could accelerate future missions.

Despite these challenges, there has been renewed interest in lunar exploration over the past decade. The Artemis program, initiated by NASA in 2017, aims to return humans to the moon by 2025.

Artemis I, an uncrewed test flight of the Space Launch System (SLS) rocket and Orion spacecraft, was successfully conducted in 2022. Artemis II, slated for 2024, will carry astronauts around the moon, setting the stage for Artemis III, which plans to land the first woman and the next man on the lunar surface.

Private industry has also played a pivotal role in advancing lunar exploration. SpaceX, led by Elon Musk, has developed the Starship spacecraft, which NASA selected as the lunar lander for Artemis III. Blue Origin, founded by Jeff Bezos, has also proposed lunar landers and collaborated with NASA on various projects. These partnerships have the potential to reduce costs and accelerate timelines, making lunar missions more feasible.

In addition to Artemis, other NASA projects are laying the groundwork for sustainable lunar exploration. The Lunar Gateway, a small space station planned for orbit around the moon, will serve as a staging point for missions to the lunar surface and beyond.

This collaborative effort involves international partners, including the European Space Agency (ESA), Japan, and Canada. The Gateway will support longer-duration missions by providing living quarters, laboratories, and docking capabilities for spacecraft.

NASA’s Commercial Lunar Payload Services (CLPS) initiative is another crucial component of the return to the moon. Through CLPS, NASA is partnering with private companies to deliver science and technology payloads to the lunar surface.

These robotic missions will help pave the way for human exploration by testing new technologies, mapping resources, and conducting scientific research. Companies like Astrobotic and Intuitive Machines are leading the charge, with planned lunar landings in the coming years.

International efforts are also advancing lunar exploration. China’s Chang’e program continues to make strides, with plans to establish a lunar research station in the 2030s. The European Space Agency’s Moon Village concept envisions a cooperative international settlement on the moon, fostering scientific collaboration and resource sharing. These initiatives highlight the growing importance of the moon as a focal point for global space exploration.

The discovery of water ice in the moon’s polar regions has been a game-changer for exploration. Scientists like Anthony Colaprete, who led the LCROSS mission, have emphasized the potential of these resources for supporting sustainable human presence. Water can be split into hydrogen and oxygen for rocket fuel or used to sustain life, reducing reliance on Earth-based supplies and enabling deeper space missions.

NASA is also exploring innovative technologies to enhance lunar exploration. For instance, the Lunar Surface Innovation Initiative focuses on developing systems for energy storage, autonomous construction, and extreme environment survival. These advancements will be critical for establishing a permanent human presence on the moon.

The renewed focus on the moon is not just about exploration but also about preparing for more ambitious missions to Mars and beyond. NASA views the moon as a testbed for developing technologies and systems needed for long-duration space travel. Establishing a sustainable lunar presence could pave the way for humanity’s expansion into the solar system.

In summary, the United States has not returned to the moon since Apollo due to a complex interplay of technological, political, financial, and international factors. However, recent advancements and discoveries have reignited interest and opened new opportunities.

With the Artemis program and contributions from private industry, humanity is on the brink of a new era of lunar exploration. If current plans hold, astronauts could once again set foot on the moon within the next few years, heralding a new chapter in our journey to the stars.

Note: Materials provided above by The Brighter Side of News. Content may be edited for style and length.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News' newsletter.

Joseph Shavit

Head Science News Writer | Communicating Innovation & Discovery

Based in Los Angeles, Joseph Shavit is an accomplished science journalist, head science news writer and co-founder at The Brighter Side of News, where he translates cutting-edge discoveries into compelling stories for a broad audience. With a strong background spanning science, business, product management, media leadership, and entrepreneurship, Joseph brings a unique perspective to science communication. His expertise allows him to uncover the intersection of technological advancements and market potential, shedding light on how groundbreaking research evolves into transformative products and industries.