Universal blood type organs created in groundbreaking procedure

Researchers have proven that it’s possible to convert the blood type of an organ, creating a universal organ that would avoid rejection.

[Feb 28, 2022: Chris Melore]

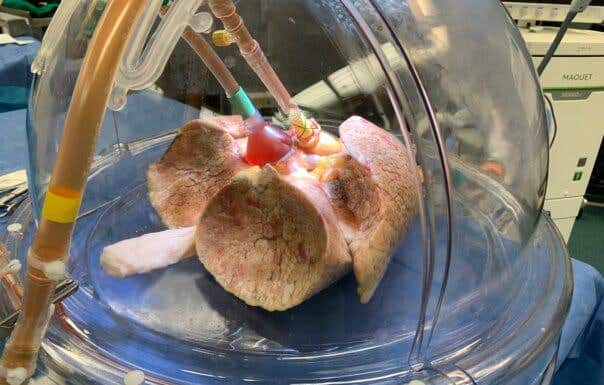

Universal blood type organs (CREDIT: University Health Network)

TORONTO, Ontario — A revolutionary procedure could make donor organs available for more patients — regardless of their blood type. Researchers from the University Health Network in Toronto have proven that it’s possible to convert the blood type of an organ, creating a universal organ that would avoid rejection during transplants.

The procedure, conducted at the Latner Thoracic Surgery Research Laboratories and UHN’s Ajmera Transplant Centre, changed the lungs from a donor with type A blood into an organ with type O blood. Scientists consider type O the universal donor type. The breakthrough may significantly cut down on the disparity in organ transplant availability and shorten transplant waiting lists worldwide.

“With the current matching system, wait times can be considerably longer for patients who need a transplant depending on their blood type,” explains senior author Dr. Marcelo Cypel, Surgical Director of the Ajmera Transplant Centre, in a media release.

“Having universal organs means we could eliminate the blood-matching barrier and prioritize patients by medical urgency, saving more lives and wasting less organs,” adds Dr. Cypel, who is also a thoracic surgeon at UHN’s Sprott Department of Surgery.

Related Stories:

Why is blood type so important?

A person’s blood type is dependent upon the antigens sitting on the surface of their red blood cells. People with type A blood have A antigens on their cells, while type B has B antigens and type AB has both. People with type O blood, however, have no antigens on the surface of their cells.

The reason this is important is because these antigens trigger an immune response if they’re foreign to a person’s body. This is also why patients needing a blood transfusion can only receive blood from donors with the same blood type — or from universal type O donors.

This problem also complicates organ donations. Researchers explain that antigens A and B are present on the surfaces of organs as well. Even people with type O blood have problems receiving transplants from type A or B donors. Since type O patients have anti-A and anti-B antibodies in their blood, receiving an organ from a type A donor will likely result in rejection.

For these reasons, doctors have to match up organs according to blood type as well as many other factors — leading to a wait for the perfect organ which can last several years. On average, type O patients actually have the longest wait for lung transplants — sometimes twice as long as type A patients. Kidney transplant patients can also end up waiting up to five years for a compatible donor.

“This translates into mortality. Patients who are type O and need a lung transplant have a 20 percent higher risk of dying while waiting for a matched organ to become available,” says explains study first author Dr. Aizhou Wang. “If you convert all organs to universal type O, you can eliminate that barrier completely.”

How did scientists make a universal organ?

In the proof-of-concept study, Dr. Cypel’s team used the Ex Vivo Lung Perfusion (EVLP) System to pump nourishing fluids through human donor lungs from a type A patient. This process allowed the researchers to warm the lungs up to body temperature so the team could convert the organs for transplantation.

Before the procedure, the donor’s lungs were not considered suitable for an organ transplant. During the experiment, study authors treated one lung with a group of enzymes to flush out the A antigens, while leaving the other lung untreated.

From there, they tested the conversion by adding type O blood with large concentrations of anti-A antibodies to the EVLP circuit. This simulated the conditions of an ABO-incompatible transplant. Results show that the treated lung was well tolerated, meaning the lung would likely be safe from rejection if the team placed it in a human patient. Meanwhile, the untreated lung showed signs of rejection, meaning such a transplant in a human would likely fail.

Gut enzymes are key to universal organs

Dr. Stephen Withers, a biochemist at the University of British Columbia, found a group of gut enzymes in 2018 which became the first step in creating these universal organs. Researchers used the EVLP circuit to deliver these enzymes to the lungs during the new experiment.

“Enzymes are Mother Nature’s catalysts and they carry out particular reactions. This group of enzymes that we found in the human gut can cut sugars from the A and B antigens on red blood cells, converting them into universal type O cells,” Dr. Withers explains. “In this experiment, this opened a gateway to create universal blood-type organs.”

“This is a great partnership with UHN and I was amazed to learn about the ex vivo perfusion system and its impact for transplants. It is exciting to see our findings being translated to clinical research,” Dr. Withers adds.

The study authors are working on a proposal to begin a clinical trial on this new technique. They hope that trial could begin within the next 12 to 18 months.

The study is published in the journal Science Translational Medicine.

Note: Materials provided above by Chris Melore. Content may be edited for style and length.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get the Brighter Side of News' newsletter.

Tags: #New_Innovations, #Blood_Type, #Medical_News, #Organs, #Science, #Transplant, #Rejection, #Research, #The_Brighter_Side_of_News