The surprising link between common virus and Alzheimer’s disease

New research links cytomegalovirus to Alzheimer’s, identifying a unique subtype and opening possibilities for targeted antiviral treatments.

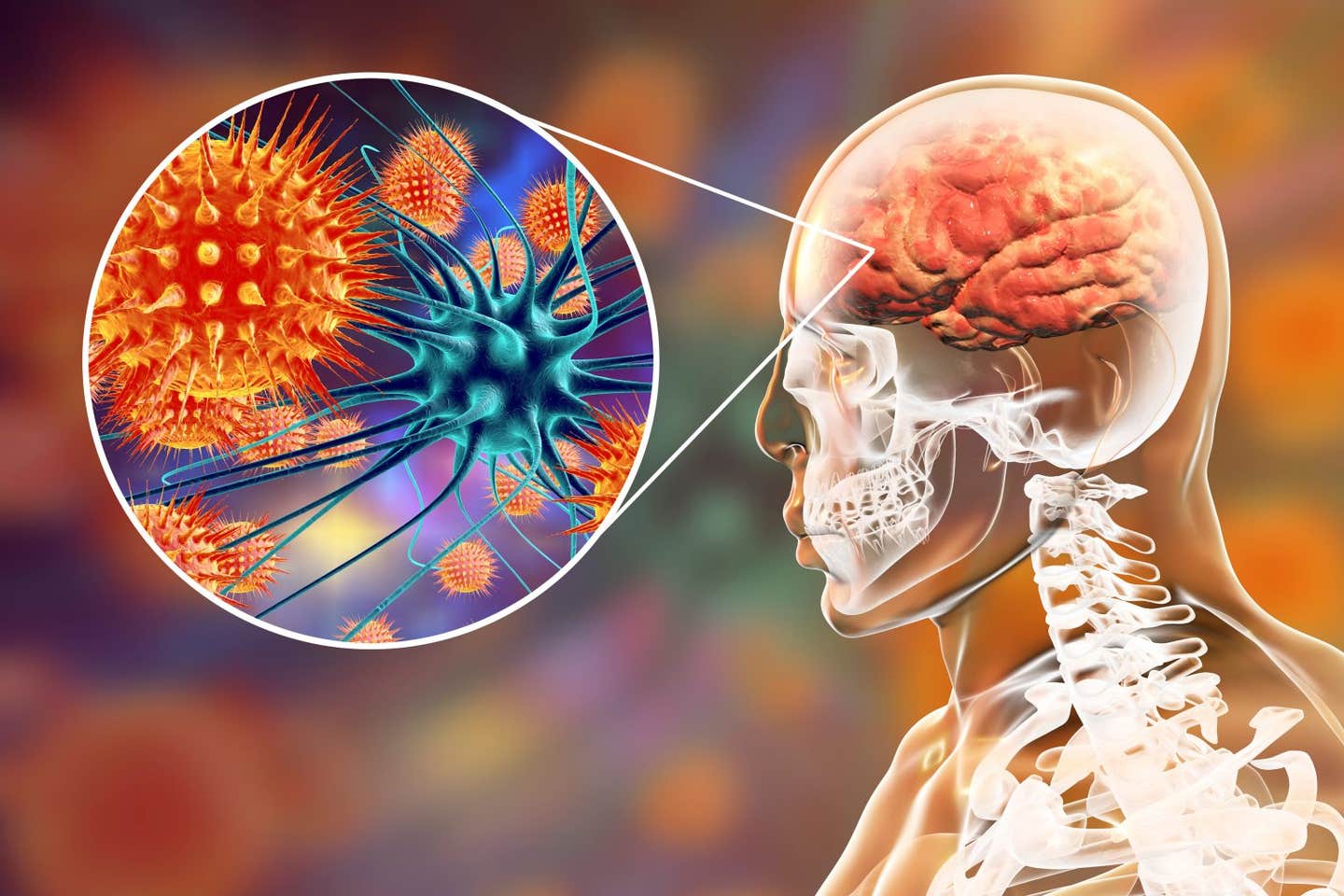

Scientists uncover a link between a common virus and Alzheimer’s, revealing a new disease subtype. (CREDIT: Westend61/Getty Images.)

Groundbreaking research has uncovered a potential link between a common virus and Alzheimer’s disease, offering fresh perspectives on how infections might contribute to neurodegenerative disorders.

Scientists at Arizona State University (ASU) and the Banner Alzheimer’s Institute, along with collaborators, have connected a chronic gut infection caused by cytomegalovirus (HCMV) to the development of Alzheimer’s in a subset of individuals. This discovery could redefine how certain cases of the disease are understood, diagnosed, and treated.

Cytomegalovirus: A Common but Mysterious Virus

Cytomegalovirus, or HCMV, is one of nine herpes viruses that most humans encounter in their lifetimes. Typically contracted through bodily fluids, this virus often remains dormant but can become active under certain conditions. While not sexually transmitted, it is widespread, with over 80% of people showing evidence of exposure by age 80.

Most infections are asymptomatic or result in mild, flu-like symptoms. However, in some cases, HCMV may persist in the gut and travel to the brain via the vagus nerve—a critical communication pathway between the gut and the brain.

Once in the brain, the virus can disrupt immune responses, potentially contributing to the hallmark changes of Alzheimer’s disease, including amyloid plaques and tau tangles.

“We think we found a biologically unique subtype of Alzheimer’s that may affect 25% to 45% of people with this disease,” explained Dr. Ben Readhead, co-first author of the study and research associate professor at ASU’s Biodesign Institute. He emphasized that this subtype features distinct biological markers, including viral presence, immune cell activation, and specific antibody responses.

Microglia and Immune Activation

Central to this discovery are microglia, the brain’s immune cells. These cells play a dual role: while they protect the brain from infections, chronic activation can lead to inflammation and neuronal damage, hallmarks of Alzheimer’s disease.

Related Stories

Recent studies using advanced single nucleus RNA sequencing (snRNAseq) revealed a subtype of microglia, marked by the CD83 gene, that is particularly abundant in Alzheimer’s patients.

This CD83(+) microglial population was identified in 47% of Alzheimer’s patients studied and in 25% of healthy controls. Its presence correlated with higher densities of amyloid plaques and tau tangles but was independent of common genetic risk factors like the APOE4 gene. These findings suggest that CD83(+) microglia might define a distinct immunological pathway contributing to the disease.

Mass spectrometry analysis of gut tissue from Alzheimer’s patients further highlighted an elevated immune response, including increased levels of immunoglobulin G4 (IgG4) antibodies. This pointed to a potential interaction between the gut microbiome and these unique microglia, reinforcing the idea that systemic infections could influence brain health.

The Role of Gut-Brain Connections

The study delved deeper into how HCMV could impact brain health. Analysis of spinal fluid and tissue samples from Alzheimer’s patients revealed antibodies specifically targeting HCMV.

The virus was detected not only in intestinal tissues but also within the vagus nerve, suggesting a direct route to the brain. Researchers demonstrated that exposing human brain cell models to HCMV led to increased production of amyloid and phosphorylated tau proteins—both associated with Alzheimer’s—and caused neuronal degeneration.

“It was critically important for us to have access to different tissues from the same individuals. That allowed us to piece the research together,” said Dr. Readhead, emphasizing the unique contributions of Arizona’s Brain and Body Donation Program in providing comprehensive tissue samples.

While the idea that infections could contribute to Alzheimer’s dates back over a century, this study provides some of the most compelling evidence yet. By identifying HCMV as a possible driver in a subset of cases, the researchers suggest that Alzheimer’s might not be a singular disease but rather a collection of conditions with diverse underlying causes.

“We’re excited about the chance to have researchers test our findings in ways that make a difference in the study, subtyping, treatment, and prevention of Alzheimer’s disease,” said Dr. Eric Reiman, senior author and Executive Director of Banner Alzheimer’s Institute.

Implications for Diagnosis and Treatment

The team is now working on a blood test to identify individuals with active HCMV infections in their gut. When combined with emerging Alzheimer’s blood tests, this diagnostic tool could help determine which patients might benefit from antiviral treatments.

If the hypothesis holds, existing antiviral drugs could potentially slow or prevent the progression of Alzheimer’s in those with chronic HCMV infections. This approach could provide a targeted therapy for a disease that currently lacks a cure and relies heavily on symptomatic treatment.

Despite these promising findings, further research is essential to confirm the role of HCMV in Alzheimer’s. Independent studies must replicate these results and explore how the virus interacts with genetic and environmental factors. Nonetheless, the integration of microbiology and neuroscience opens new avenues for understanding the systemic roots of neurodegeneration.

As Dr. Reiman noted, “We are extremely grateful to our research participants, colleagues, and supporters for the chance to advance this research in a way that none of us could have done on our own.” This collaborative effort underscores the importance of interdisciplinary approaches in tackling complex diseases like Alzheimer’s.

The potential link between HCMV and Alzheimer’s adds to a growing body of evidence suggesting that infections can influence brain health. While much remains to be discovered, this research offers hope for developing more precise diagnostic tools and targeted treatments for one of the most challenging diseases of our time.

Note: Materials provided above by The Brighter Side of News. Content may be edited for style and length.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News' newsletter.

Joseph Shavit

Head Science News Writer | Communicating Innovation & Discovery

Based in Los Angeles, Joseph Shavit is an accomplished science journalist, head science news writer and co-founder at The Brighter Side of News, where he translates cutting-edge discoveries into compelling stories for a broad audience. With a strong background spanning science, business, product management, media leadership, and entrepreneurship, Joseph brings a unique perspective to science communication. His expertise allows him to uncover the intersection of technological advancements and market potential, shedding light on how groundbreaking research evolves into transformative products and industries.