Swedish researchers developed a way to make vegan food more appetizing

Their recent innovation in the process has led to a substantial reduction in energy consumption—about 75 percent.

In the quest for more appealing plant-based foods, researchers at Lund University in Sweden are spearheading innovative strategies to enhance the texture and flavor of vegan products. At the heart of their research is the development of meat analogues—plant-based substitutes designed to mimic the texture and sensory experience of meat. This burgeoning field, although still in its nascent stages, is expected to grow exponentially.

Unlike cultivated meat, which is produced using animal stem cells, the Lund team focuses on plant proteins to recreate the fibrous structure of muscle. This shift is crucial for overcoming the often criticized rubbery texture of vegan foods available on the market. Most of these products primarily use imported soy protein, which fails to provide the satisfying chewiness meat eaters enjoy.

Karolina Östbring, a key researcher at Lund, illustrates the challenge with a simple analogy: “If you take mashed potato and fry it, your teeth go straight through—it's just soft and fluffy. When you chew meat, it's a totally different sensation.” She further explains that their objective is to introduce a similar chewiness into vegetable-based foods by simulating muscle fibers.

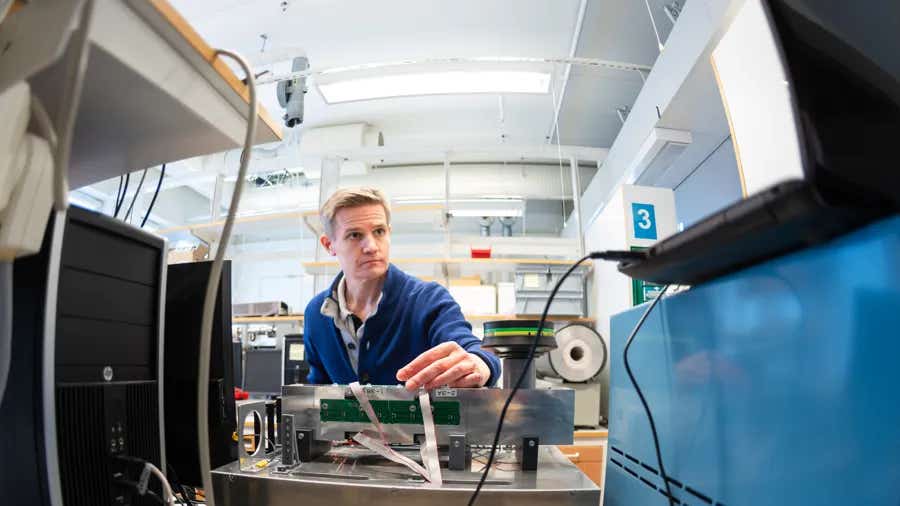

The complexity of producing high-quality meat analogues lies in the mastery of a sophisticated piece of equipment known as an extruder, which functions as a combined pressure cooker and meat grinder. “It's incredibly complicated,” says Östbring, describing the extruder as the most advanced equipment in their facility. “There is an immense number of parameters that can be set at various levels, making the process tricky but wonderful when it works.”

After five years of intensive work with the extruder, Östbring and her colleague Jeanette Purhagen have made significant strides. Their recent innovation in the process has led to a substantial reduction in energy consumption—about 75 percent—by introducing a protein solution directly into the extruder, thereby bypassing an energy-intensive drying stage.

Purhagen explains the implications of this advancement: “It was not possible to patent the discovery, as the patent system is based on adding a step rather than removing and simplifying. So, we have published the discovery instead.” This open publication allows other researchers and developers to adopt this more sustainable method.

Related Stories

The selection of raw materials is as critical as the settings of the extruder. The Lund team has experimented with a variety of plant-based proteins and fibers, such as rapeseed, hempseed, yellow peas, chickpeas, broad beans, oats, and gluten.

These ingredients often come from residual streams from agriculture and the food industry, enhancing the environmental benefits of their products.

“The research field has begun to realize that one raw material cannot do the whole job,” Östbring points out. “Rather, you need to combine two or more raw materials to attain a really good mouthfeel.” This approach helps avoid the rubbery texture that is typical of many single-ingredient plant-based foods.

One combination that has stood out in their experiments involves hempseed, particularly the residue left from hempseed oil production. Östbring is enthusiastic about hempseed’s potential: “Hempseed behaves in a really tremendous way. It contains a lot of high-quality protein, has fantastic texturing properties, and tastes good.”

When combined with gluten, hempseed develops a rounded taste and a chewy texture that was highly appreciated by their tasting panel, making it their favorite formulation.

Another promising combination was hempseed with residues from oat milk production, which also received high marks for taste and texture.

Despite their success in the lab, the Lund researchers are not moving towards commercialization themselves. However, there is significant interest from several companies in bringing these innovative vegan products to market, a process expected to take between two and five years.

Purhagen also emphasizes the broader impacts of their work, highlighting the benefits to the environment, climate, health, and animal welfare. She notes that the food industry generates various residual streams that can be repurposed to create appealing and sustainable food options.

The team at Lund University is not only advancing the science of meat analogues but also contributing to a more sustainable and ethical food system. Their work underscores the importance of texture and flavor in the acceptance of vegan foods and points towards a future where plant-based options are not just available but truly enjoyable.

For more science news stories check out our New Discoveries section at The Brighter Side of News.

Note: Materials provided above by The Brighter Side of News. Content may be edited for style and length.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get the Brighter Side of News' newsletter.