Surprising research on how the brain processes and remembers everyday events

Mental sketches of people can be transposed from one location to another, much like an animator can copy and paste a character into scenes

[Apr. 3, 2023: JJ Shavit, The Brighter Side of News]

Researchers have published a study on how the brain processes and remembers everyday events. (CREDIT: Creative Commons)

Washington University in St. Louis Assistant Professor of Psychological and Brain Sciences, Zachariah Reagh, and University of California, Davis co-author Charan Ranganath, have published a study on how the brain processes and remembers everyday events. Using functional MRI scanners, the researchers monitored the brains of subjects watching short videos of realistic scenes, such as men and women working on laptops in a cafe or shopping in a grocery store.

The research subjects immediately described the scenes with as much detail as they could muster, and the researchers found that different parts of the brain worked together to understand and remember the situation.

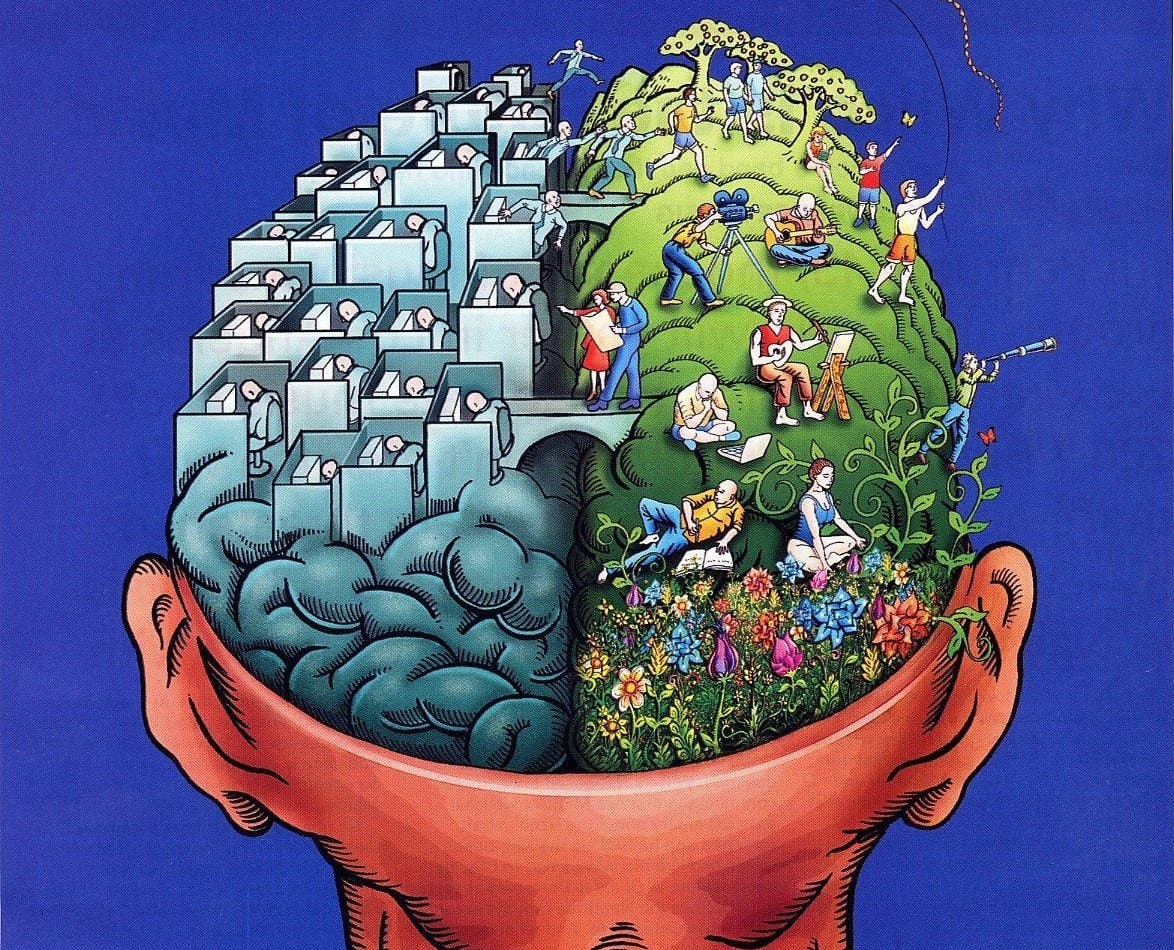

Networks in the front part of the temporal lobe, a region of the brain long known to play an important role in memory, focused on the subject regardless of their surroundings. The posterior medial network, which involves the parietal lobe toward the back of the brain, paid more attention to the environment. Those networks then sent information to the hippocampus, which combined the signals to create a cohesive scene.

Previously, researchers had used very simple objects and scenarios to study the different building blocks of memories, such as a picture of an apple on a beach. However, Reagh said that life is not so simple, and he wondered if anyone had done these types of studies with dynamic real-world situations, and the answer was no.

Related Stories

The new study suggests that the brain makes mental sketches of people that can be transposed from one location to another, much like an animator can copy and paste a character into different scenes.

Reagh and Ranganath found that some subjects could recall the scenes in the café and grocery store more completely and accurately than others. Those with the clearest memories used the same neural patterns when recalling scenes that they used while watching the clips. “The more you can bring those patterns back online while describing an event, the better your overall memory,” Reagh said.

However, Reagh pointed out that even memories that seem crisp and vivid may not actually reflect reality. “I tell my students that your memory is not a video camera. It doesn’t give you a perfect representation of what happened. Your brain is telling you a story.”

Reagh is one of the Washington University faculty members involved in the research cluster “The Storytelling Lab: Bridging Science, Technology, and Creativity,” part of the Incubator for Transdisciplinary Futures. Led by Jeff Zacks, chair of the Department of Psychological & Brain Sciences, with Ian Bogost and Colin Burnett, the Storytelling Lab explores the psychology and neurology of narratives.

The study’s findings reveal a new understanding of how the brain creates and remembers everyday events. The research is significant because it reveals how different parts of the brain interact to understand and store memories.

Additionally, the research provides insight into how people remember things, which may be useful in developing new therapies for memory loss. The study also has implications for how memories may be manipulated, which could have implications for criminal investigations and other legal matters.

The Study’s Methodology

The study was conducted by Reagh and Ranganath, who used functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) to scan the brains of 23 adults while they watched short videos of realistic scenes, such as men and women working on laptops in a cafe or shopping in a grocery store. After each video, the participants immediately described the scene in as much detail as possible.

Experimental design and trial structure. Eight videos were designed to systematically combine the information in events about local entities (i.e., central person) and contexts (i.e., specific location), with an additional layer of context type (i.e., café vs. grocery store). (CREDIT: Nature Communications)

The researchers found that different parts of the brain work together to understand and remember the situation. Networks in the front part of the temporal lobe, a region of the brain long known to play an important role in memory, focused on the subject regardless of their surroundings.

The posterior medial network, which involves the parietal lobe toward the back of the brain, paid more attention to the environment. Those networks then sent information to the hippocampus, a region of the brain known to play a crucial role in consolidating memories. The hippocampus combines the signals from these networks to create a cohesive scene.

The study also shed light on how the brain creates mental sketches of people that can be transposed from one location to another, much like an animator can copy and paste a character into different scenes. "It may not seem intuitive that your brain can create a sketch of a family member that it moves from place to place, but it's very efficient," Reagh said.

Model matrices based on hypothesized representational profiles. Event-by-event correlation matrices resulting from pattern similarity analyses were compared to hypothesized model matrices depicting Character, Context, Schema, and Episode-Specific representations via point-biserial correlations. (CREDIT: Nature Communications)

The findings have important implications for understanding how memories are formed and retrieved in everyday life. "We all have these experiences of remembering scenes and events from our daily lives, and it's fascinating to see how the brain is able to process and store these memories," said Ranganath, co-author of the study.

Moreover, the study suggests that the more vividly a person can recall a memory, the more likely they are to use the same neural patterns that were activated when the memory was first formed. "The more you can bring those patterns back online while describing an event, the better your overall memory," Reagh explained.

However, the study also revealed that even memories that seem crisp and vivid may not actually reflect reality. "I tell my students that your memory is not a video camera. It doesn't give you a perfect representation of what happened. Your brain is telling you a story," Reagh cautioned.

Across-event pattern similarity at encoding. PM Network pattern similarity results most strongly fit the Context model matrix. (CREDIT: Nature Communications)

The research was conducted by Reagh and Ranganath, who used functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) to monitor the brains of study participants while they watched short videos of everyday scenes, such as people working on laptops in a cafe or shopping in a grocery store. The subjects were then asked to describe the scenes with as much detail as they could remember.

The study builds on previous research that has used simpler objects and scenarios to study the building blocks of memory. Reagh said he was curious to explore whether these findings could be extended to more complex, real-world situations. "I wondered if anyone had done these types of studies with dynamic real-world situations and, shockingly, the answer was no," he said.

Reagh is one of the faculty members at Washington University involved in the research cluster "The Storytelling Lab: Bridging Science, Technology, and Creativity," which is part of the Incubator for Transdisciplinary Futures. Led by Jeff Zacks, chair of the Department of Psychological & Brain Sciences, with Ian Bogost and Colin Burnett, the Storytelling Lab explores the psychology and neurology of narratives.

In the future, Reagh plans to study the brain activity and memory of people watching more complicated stories. "The Storytelling Lab fits perfectly with the scientific questions that I find most exciting," he said. "I want to understand how the brain creates and remembers narratives."

Note: Materials provided above by The Brighter Side of News. Content may be edited for style and length.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get the Brighter Side of News' newsletter.

Joseph Shavit

Head Science News Writer | Communicating Innovation & Discovery

Based in Los Angeles, Joseph Shavit is an accomplished science journalist, head science news writer and co-founder at The Brighter Side of News, where he translates cutting-edge discoveries into compelling stories for a broad audience. With a strong background spanning science, business, product management, media leadership, and entrepreneurship, Joseph brings a unique perspective to science communication. His expertise allows him to uncover the intersection of technological advancements and market potential, shedding light on how groundbreaking research evolves into transformative products and industries.