Supernova explosion blamed for two extinction events on Earth

OB stars fuel the universe with life and destruction. Scientists link past extinctions to supernovae while mapping these stellar giants.

Scientists link two mass extinctions to supernovae while mapping OB stars to study star formation, galaxy evolution, and cosmic destruction. (CREDIT: muratart / Shutterstock)

Some of the most massive and influential stars in the universe are OB stars. These blue giants, many times more massive than the Sun, are short-lived but powerful forces that shape their surroundings. They are crucial in understanding star formation, galactic structure, and even planetary evolution.

Their intense radiation ionizes surrounding gas, creating glowing HII regions and bubbles of charged particles. These processes influence the interstellar medium by injecting energy and momentum, slowing down star formation by pushing molecular gas out of star-forming regions.

OB stars are key markers of spiral arms in galaxies. Their brightness makes them excellent tools for tracing stellar populations, and their short lifespans keep them near their birthplaces. Researchers use them to study the structure of the Milky Way and estimate the rates of massive stellar events like supernovae.

For decades, astronomers have compiled OB star catalogs to improve our understanding of these cosmic giants. Early surveys, such as the Case-Hamburg surveys and the Alma Luminous Stars catalog, provided valuable data. However, these efforts favored the brightest stars and overlooked dimmer ones due to observational limitations.

The arrival of the Gaia space telescope revolutionized the study of OB stars by offering precise astrometric and photometric data, leading to more comprehensive star censuses. Recent studies, including Gaia's golden sample of OBA stars, have vastly improved our knowledge of their distribution.

OB Stars and Supernovae: The Creators and Destroyers

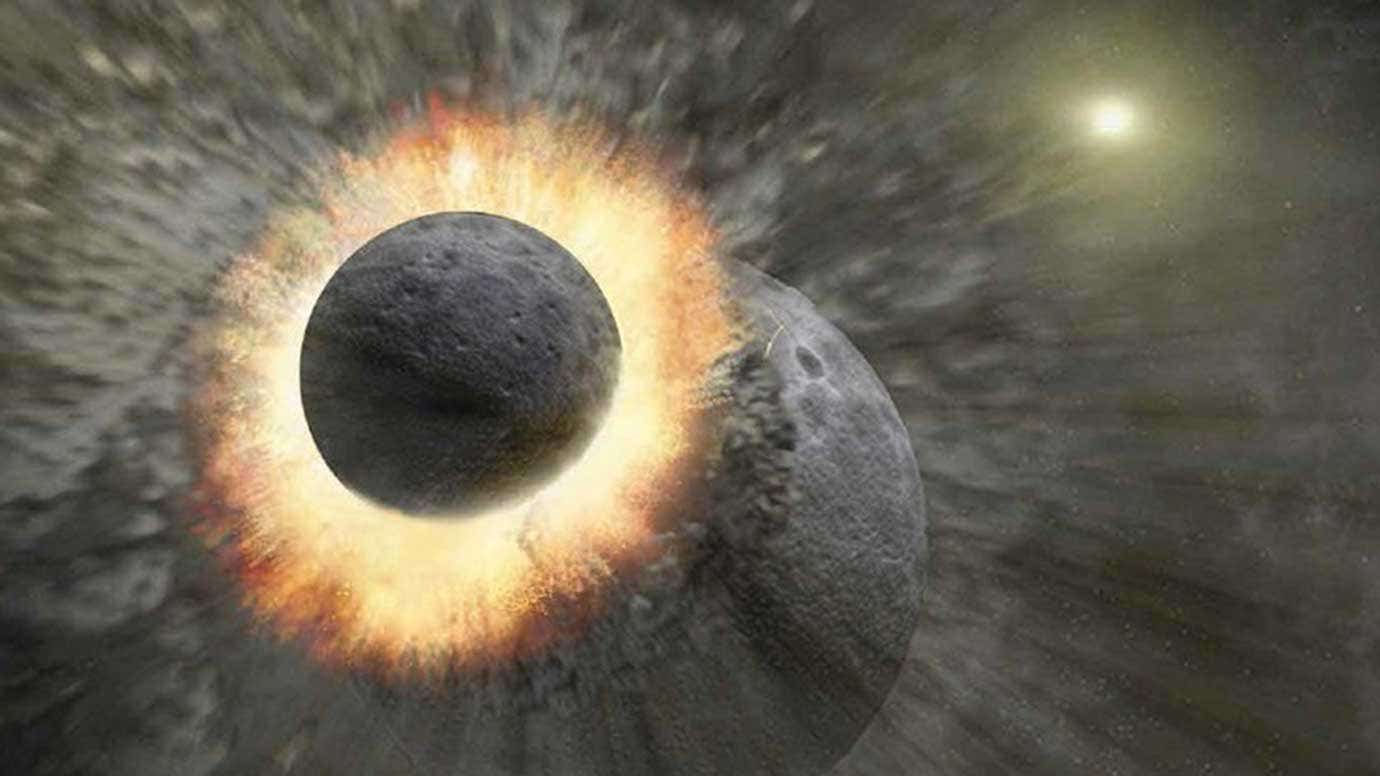

The final act of an OB star's life is one of the most violent events in the universe: a supernova explosion. Stars at least eight times the Sun’s mass undergo core collapse, resulting in a massive explosion that disperses heavy elements into space. These elements become the building blocks for new stars, planets, and even life. Without supernovae, essential elements like carbon, oxygen, and iron would not exist in their current abundance.

However, these explosions are not just creators—they are also destroyers. A growing body of research suggests that at least two mass extinctions on Earth may have been caused by nearby supernovae.

Related Stories

Scientists at Keele University believe that the Ordovician (445 million years ago) and late Devonian (372 million years ago) extinctions were triggered by the effects of supernovae. The Ordovician event wiped out 60% of marine invertebrates, while the Devonian extinction led to the disappearance of 70% of species, reshaping ancient ecosystems.

The primary threat from a supernova comes from high-energy radiation. When a nearby OB star explodes, it sends a burst of X-rays and gamma rays toward Earth, potentially stripping away the ozone layer. This exposure allows harmful ultraviolet radiation from the Sun to reach the surface, leading to genetic mutations and ecological collapse. Supernovae could also trigger acid rain, further altering Earth's climate and environment.

Tracing Past Extinctions to Stellar Explosions

Despite decades of research, scientists have struggled to identify definitive causes for many ancient extinction events. Geological evidence shows a correlation between mass extinctions and disruptions to the ozone layer. A supernova occurring within 65 light-years of Earth could have produced the radiation needed to deplete atmospheric ozone, allowing deadly UV rays to reach the surface.

By conducting a new census of OB stars within a kiloparsec (3,260 light-years) of the Sun, researchers have improved estimates of how often supernovae occur near Earth. The findings suggest that the supernova rate near the Sun aligns with the timing of these extinction events.

The study, published in Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, supports the idea that cosmic forces have shaped life on Earth in dramatic ways.

Lead researcher Dr. Alexis Quintana, now at the University of Alicante, explains, “Supernova explosions bring heavy chemical elements into the interstellar medium, which are then used to form new stars and planets. But if a planet, including Earth, is located too close to this kind of event, this can have devastating effects.”

Dr. Nick Wright from Keele University adds, “Supernova explosions are some of the most energetic explosions in the universe. If a massive star were to explode as a supernova close to Earth, the results would be devastating for life on Earth. This research suggests that this may have already happened.”

Are We at Risk of Another Supernova Event?

Astronomers estimate that galaxies like the Milky Way experience one to two supernovae per century. Fortunately, only two nearby stars—Antares and Betelgeuse—are candidates for supernova explosions in the foreseeable future. Both are over 500 light-years away, and simulations suggest that a supernova at that distance would not significantly affect Earth.

While no immediate threats exist, studying supernovae remains critical. Beyond their potential impact on life, they play a role in the formation of neutron stars and black holes, shaping galaxies over billions of years. Future gravitational wave detectors will help scientists study these events more precisely, offering insights into their frequency and effects on the cosmos.

Understanding OB stars and their life cycles helps astronomers refine models of star formation and extinction rates. These studies provide a clearer picture of the forces shaping the universe—and Earth’s own history.

Though no cosmic catastrophe looms in the near future, the past suggests that life on Earth has already endured the effects of stellar explosions, reminding us that our place in the universe is both precarious and extraordinary.

Note: Materials provided above by The Brighter Side of News. Content may be edited for style and length.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News' newsletter.

Joseph Shavit

Head Science News Writer | Communicating Innovation & Discovery

Based in Los Angeles, Joseph Shavit is an accomplished science journalist, head science news writer and co-founder at The Brighter Side of News, where he translates cutting-edge discoveries into compelling stories for a broad audience. With a strong background spanning science, business, product management, media leadership, and entrepreneurship, Joseph brings a unique perspective to science communication. His expertise allows him to uncover the intersection of technological advancements and market potential, shedding light on how groundbreaking research evolves into transformative products and industries.