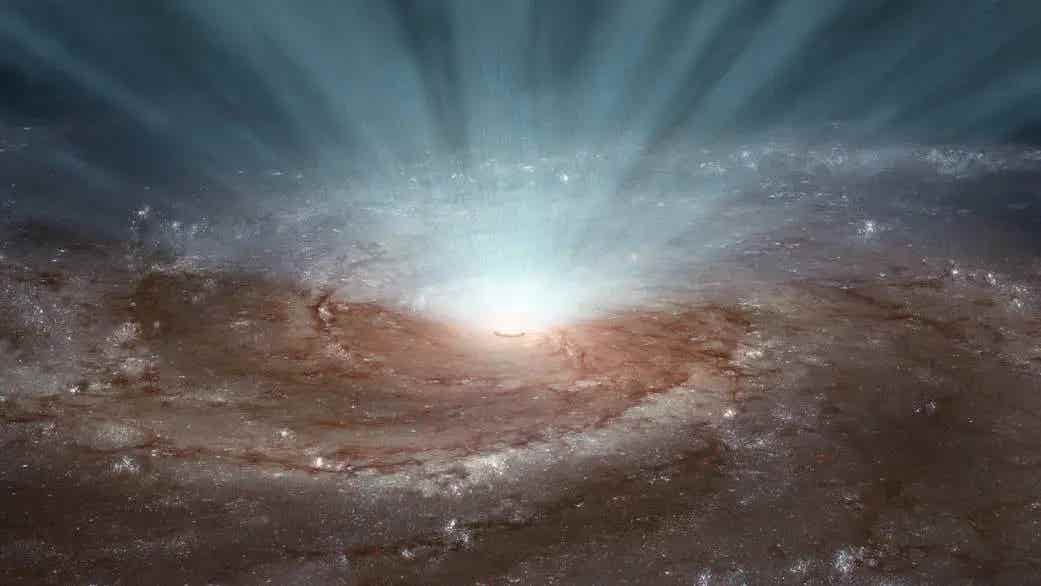

Supermassive black hole winds can reshape galaxies

Clouds of gas are speeding up to more than 10,000 miles per second, driven by blasts of radiation from a supermassive black hole

Clouds of gas in a distant galaxy are speeding up to more than 10,000 miles per second, driven by blasts of radiation from a supermassive black hole at the galaxy's center. This discovery sheds light on how active black holes can continuously shape their galaxies, either promoting or halting the formation of new stars.

A team of researchers led by University of Wisconsin–Madison astronomy professor Catherine Grier and recent graduate Robert Wheatley made this revelation. They used years of data from a quasar, a bright and turbulent kind of black hole, located billions of light-years away in the constellation Boötes. They presented their findings at the 244th meeting of the American Astronomical Society in Madison.

Scientists believe that black holes are found at the center of most galaxies. Quasars are supermassive black holes surrounded by disks of matter being pulled in by the black hole's immense gravitational force.

“The material in that disk is always falling into the black hole, and the friction of that pulling heats up the disk, making it very hot and bright,” says Grier. “These quasars are really luminous, and because there’s a large range of temperatures from the interior to the far parts of the disk, their emission covers almost all of the electromagnetic spectrum.”

The intense light from quasars makes them visible even from as far as 13 billion light-years away. Their broad range of radiation makes them particularly useful for astronomers to study the early universe.

Researchers used over eight years of observations of a quasar called SBS 1408+544, collected by the Sloan Digital Sky Survey's Black Hole Mapper Reverberation Mapping Project. They tracked winds made of gaseous carbon by spotting light from the quasar that was being absorbed by the gas. Instead of being absorbed at the expected spot in the spectrum, the shadow shifted further with each new observation of SBS 1408+544.

Related Stories

“That shift tells us the gas is moving fast, and faster all the time,” says Wheatley. “The wind is accelerating because it’s being pushed by radiation blasted off the accretion disk.”

Scientists, including Grier, have suggested they’ve observed accelerating winds from black hole accretion disks before, but this wasn't backed by substantial data. The new results came from about 130 observations of SBS 1408+544 over nearly a decade, allowing the team to confirm the increase in velocity with high confidence.

The winds pushing gas out from the quasar are significant because they might influence the evolution of the surrounding galaxy.

“If they’re energetic enough, the winds may travel all the way out into the host galaxy, where they could have a significant impact,” Wheatley explains.

Depending on the circumstances, a quasar’s winds could either compress gas to speed up star formation or blow away the gas, preventing new stars from forming.

“Supermassive black holes are big, but they’re really tiny compared to their galaxies,” says Grier. “That doesn’t mean they can’t ‘talk’ to each other, and this is a way for one to talk to the other that we will have to account for when we model the effects of these kinds of black holes.”

Grier's work is supported by the National Science Foundation, highlighting the importance of funding for astronomical research. This discovery is a crucial piece in understanding the dynamic relationship between black holes and their host galaxies, providing insights that could refine our models of galaxy evolution.

The study of quasars and their winds continues to be a vital field in astronomy, offering a glimpse into the complex mechanisms at play in the universe. By observing these distant objects, scientists can piece together the history and behavior of galaxies, shedding light on the processes that shape the cosmos.

The study of SBS 1408+544, published in The Astrophysical Journal included collaborators at York University, Pennsylvania State University, University of Arizona and others.

Note: Materials provided above by The Brighter Side of News. Content may be edited for style and length.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get the Brighter Side of News' newsletter.

Joshua Shavit

Science & Technology Writer | AI and Robotics Reporter

Joshua Shavit is a Los Angeles-based science and technology writer with a passion for exploring the breakthroughs shaping the future. As a contributor to The Brighter Side of News, he focuses on positive and transformative advancements in AI, technology, physics, engineering, robotics and space science. Joshua is currently working towards a Bachelor of Science in Business Administration at the University of California, Berkeley. He combines his academic background with a talent for storytelling, making complex scientific discoveries engaging and accessible. His work highlights the innovators behind the ideas, bringing readers closer to the people driving progress.