Student accidentally finds ancient Mayan city hidden in Mexican jungle

A massive Maya city, Valeriana, uncovered in Mexico’s jungle reveals ancient urban density, advanced infrastructure, and climate impacts on Maya society.

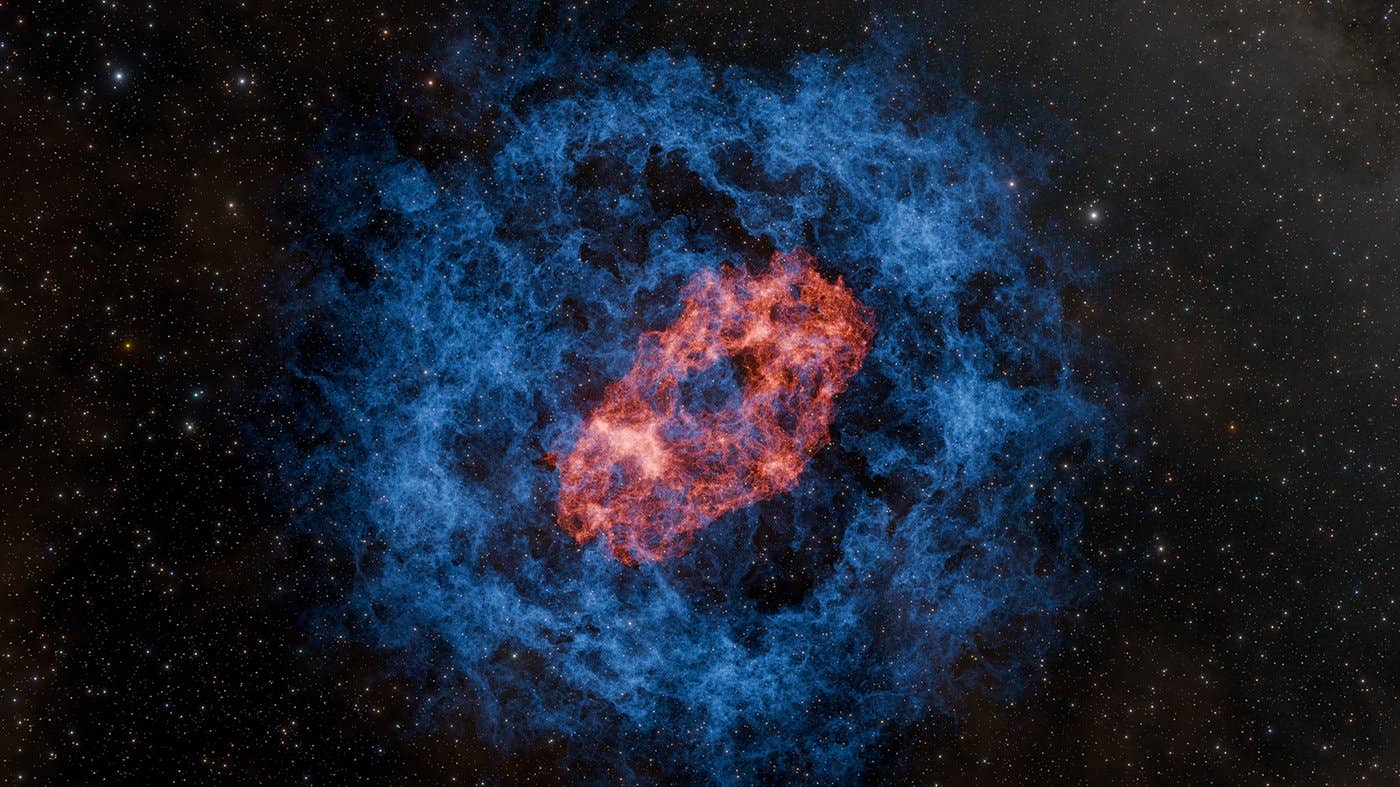

Researchers have discovered an ancient Maya city, Valeriana, hidden in Mexico’s dense jungle. (CREDIT: Marcello Canuto)

The lush jungles of Mexico have revealed a hidden marvel: an ancient Maya city sprawling under centuries of dense growth. Discovered in the southeastern state of Campeche and dubbed "Valeriana," the city presents a wealth of architectural and cultural insights into the Maya civilization that once flourished in Latin America.

Using advanced laser mapping technology known as Lidar, archaeologists have uncovered pyramids, sports fields, causeways, plazas, and amphitheaters within this extensive urban landscape, believed to rival even the famed Calakmul site in both size and complexity.

The serendipitous discovery emerged when Luke Auld-Thomas, a PhD student from Tulane University, stumbled upon a data set while casually browsing the internet. “I was on something like page 16 of a Google search,” Auld-Thomas recalled, describing how he uncovered a laser survey originally intended for environmental monitoring by a Mexican organization.

Conducted in 2013 as part of the Alianza project to reduce emissions from deforestation and degradation, this Lidar survey captured around 122 square kilometers of land, revealing structures that conventional exploration methods had missed. Lidar, which stands for Light Detection and Ranging, uses laser pulses from aircraft to detect hidden objects below the tree canopy.

When Auld-Thomas processed the data with archaeological methods, the existence of a vast, well-organized city emerged—a discovery hinting that Valeriana may have housed 30,000 to 50,000 residents at its peak between 750 and 850 AD, far exceeding the region’s current population.

Named after a nearby lagoon, Valeriana covers approximately 16.6 square kilometers and contains two central zones, each about two kilometers apart, connected by densely packed houses and causeways. The city includes two large plazas with temple pyramids, where Maya citizens likely gathered for worship and community events, and structures dedicated to ancient ball games—a hallmark of Maya social and ritual life.

In addition to its impressive architectural features, Valeriana boasts a reservoir, an engineering feat demonstrating the Maya’s understanding of water management, critical to sustaining a sizable population in a challenging environment.

Related Stories

Valeriana’s location, just a 15-minute hike from a major road near Xpujil, suggests that the city may have been “hidden in plain sight” for centuries. Although there are no known images of the site due to the dense jungle cover, local residents have long suspected that ancient structures lay beneath the mounds of earth.

Auld-Thomas and his team documented a total of 6,764 buildings across three surveyed sites, underscoring the scale and density of Maya settlement in the region. According to archaeologist Marcello Canuto, a co-author on the study, this discovery challenges Western narratives that equate tropical regions with inhospitable, “wild” lands incapable of supporting complex societies.

“This part of the world was home to rich and complex cultures,” Canuto noted, shifting the perception of the Tropics as a mere refuge for declining civilizations.

The Maya civilization, known for its remarkable achievements in art, architecture, astronomy, and mathematics, flourished between 250 and 900 AD, extending its influence across present-day southern Mexico, Guatemala, Belize, El Salvador, and Honduras.

Valeriana, with its dense settlement patterns, joins an array of ancient Maya cities that have only recently been brought to light through modern technological advances. According to Professor Elizabeth Graham from University College London, who was not involved in the study, these discoveries validate the idea that the Maya lived in sophisticated urban centers rather than isolated villages.

“The landscape is definitely settled...and not, as it appears to the naked eye, uninhabited or ‘wild,’” Graham commented.

One of the more striking aspects of this discovery is that Lidar technology has enabled archaeologists to map vast areas once deemed inaccessible or impractical for traditional survey methods. “Lidar has revolutionized how we survey regions blanketed by dense vegetation,” Canuto explained.

In his early career, archaeologists relied on manual surveys, inching through forests with limited equipment. In just over a decade, however, Lidar has allowed researchers to map nearly ten times the area that was previously possible in a century, revealing a vast network of Maya cities across the Mesoamerican landscape.

Although these findings are groundbreaking, they also present a challenge: the sheer number of newly uncovered sites far outstrips the resources available for excavation. “One downside of discovering so many Maya cities in the era of Lidar is that there are more than we can ever hope to study,” Auld-Thomas said. While he hopes to visit Valeriana due to its close proximity to major roads, there is no guarantee that he or his colleagues will have the opportunity to conduct an extensive excavation at the site.

Researchers believe that the city’s eventual abandonment may have been triggered by a combination of environmental and social factors. By 800 AD, much of the Maya world was undergoing profound changes. Auld-Thomas suggests that a densely packed population and strained resources likely left the city vulnerable to climate shifts.

“It’s suggesting that the landscape was just completely full of people at the onset of drought conditions and it didn’t have a lot of flexibility left,” he explained. This lack of adaptability may have led to the unraveling of Maya society as people migrated to more sustainable regions. Additionally, warfare and the eventual Spanish conquest in the 16th century further contributed to the decline of Maya city-states.

Valeriana’s discovery emphasizes the ongoing evolution of our understanding of ancient Maya civilization and the importance of advanced technologies in rewriting history.

With Lidar revealing extensive archaeological sites hidden beneath dense tropical forests, researchers now have a clearer picture of how the Maya adapted to and shaped their environment, building urban centers that could sustain large populations even in challenging landscapes.

Yet, despite these technological advancements, mysteries remain. As the archaeologists involved in the Valeriana discovery have shown, each new site not only answers questions but also raises new ones, pushing the boundaries of what we know about one of history’s most influential civilizations.

Note: Materials provided above by The Brighter Side of News. Content may be edited for style and length.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News' newsletter.