Scientists discovered a 240-million-year-old ‘Dragon’ in China

The fossil, belonging to the Dinocephalosaurus orientalis, dates back 240 million years to the Triassic period and was unearthed in China

Restoration of Dinocephalosaurus orientalis depicted among a shoal of the large, predatory actinopterygian fish, Saurichthys. (CREDIT: Marlene Donnelly)

In the Year of the Dragon, scientists have made an exciting discovery: a complete fossil of an aquatic reptile resembling a "Chinese dragon" due to its snake-like features and elongated neck.

The fossil, belonging to the Dinocephalosaurus orientalis, dates back 240 million years to the Triassic period and was unearthed in Guizhou Province, southern China.

Although the reptile was initially identified in 2003, this latest find, measuring about 16 feet in length, provides a more comprehensive view of the creature, enabling scientists to depict it in its entirety for the first time.

Dinocephalosaurus was a type of sea reptile that lived in China during a time called the Triassic period. It had a long neck and lived in water. Scientists have only found one kind of Dinocephalosaurus, called D. orientalis.

Related Stories

It was named by someone named Li in 2003. Unlike other sea reptiles with long necks, Dinocephalosaurus didn't stretch out its individual neck bones. Instead, it added more bones to its neck, making it long.

Scientists think it belonged to a group different from other similar reptiles, like Pectodens. They named this group Dinocephalosauridae in 2021.

Like other sea reptiles, Dinocephalosaurus probably used its long neck to catch food, like fish, with its sharp teeth. Some scientists think it might have sucked in its food, but not everyone agrees. Because of its limb structure, which was like paddles, it likely spent most of its time in the water and couldn't move well on land.

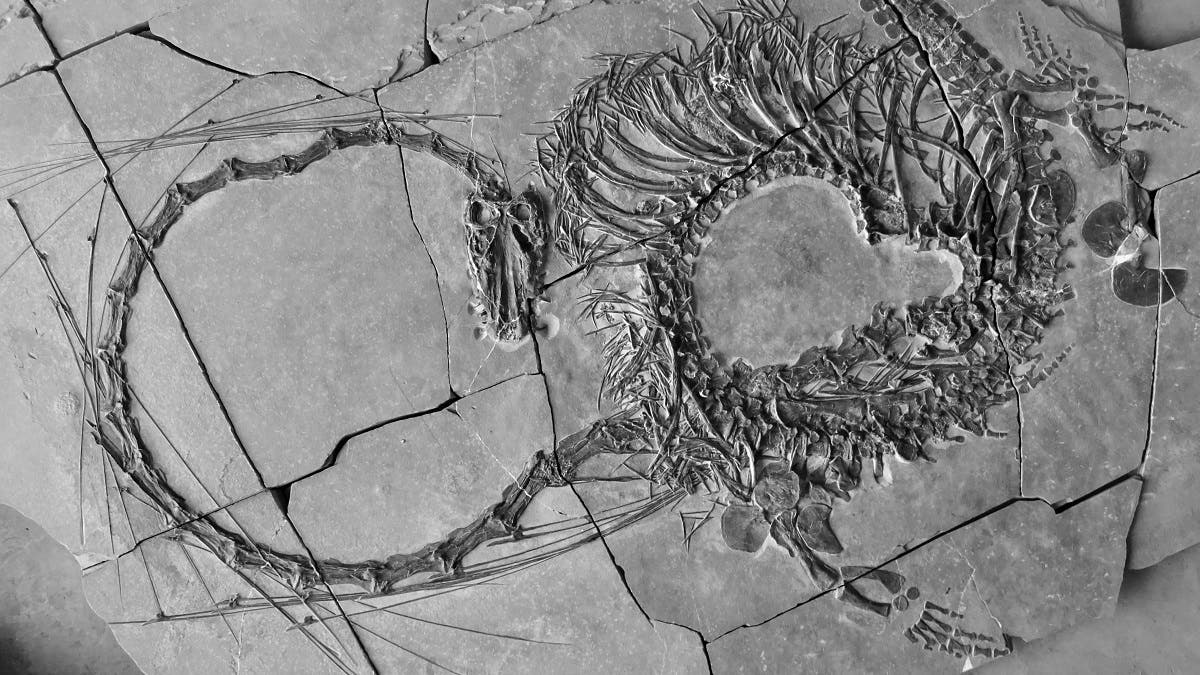

Dinocephalosaurus orientalis fossil. (CREDIT: National Museums Scotland)

Nick Fraser, head of the National Museum of Scotland's Department of Natural Sciences, expressed his fascination with the discovery, stating, “This discovery allows us to see this remarkable long-necked animal in full for the very first time. It is yet one more example of the weird and wonderful world of the Triassic that continues to baffle palaeontologists. We are certain that it will capture imaginations across the globe due to its striking appearance, reminiscent of the long and snake-like, mythical Chinese Dragon.”

Professor Li Chun from the Institute of Vertebrate Palaeontology and Palaeoanthropology highlighted the international collaboration involved in the discovery, “This has been an international effort. Working together with colleagues from the United States of America, the United Kingdom and Europe, we used newly discovered specimens housed at the Chinese Academy of Sciences to build on our existing knowledge of this animal. Among all of the extraordinary finds we have made in the Triassic of Guizhou Province, Dinocephalosaurus probably stands out as the most remarkable.”

Dinocephalosaurus orientalis fossil. (CREDIT: National Museums Scotland)

The research team examined the peculiar reptile at the Institute of Vertebrate Palaeontology and Palaeoanthropology in Beijing. They observed flippered limbs and remarkably preserved fish in its stomach, indicating that the reptile was well-adapted to oceanic environments.

"We used newly discovered specimens housed at the Chinese Academy of Sciences to build on our existing knowledge of this animal," explained Chun. "Among all of the extraordinary finds we have made in the Triassic of Guizhou Province,

Dinocephalosaurus probably stands out as the most remarkable."

Dinocephalosaurus orientalis, ZMNH M8727, interpretative drawings of selected cranial remains. (CREDIT: Cambridge University Press)

Stephan Spiekman, a postdoctoral researcher at the Stuttgart State Museum of Natural History, expressed hope that further research would shed light on the evolution of this group of animals, particularly regarding the function of its extraordinarily long neck.

The neck comprises 32 separate vertebrae, surpassing the length of the creature's body and tail combined. A study published by the Cambridge University Press suggests that the neck likely played a crucial role in feeding.

Note: Materials provided above by The Brighter Side of News. Content may be edited for style and length.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get the Brighter Side of News' newsletter.

Joshua Shavit

Science & Technology Writer | AI and Robotics Reporter

Joshua Shavit is a Los Angeles-based science and technology writer with a passion for exploring the breakthroughs shaping the future. As a contributor to The Brighter Side of News, he focuses on positive and transformative advancements in AI, technology, physics, engineering, robotics and space science. Joshua is currently working towards a Bachelor of Science in Business Administration at the University of California, Berkeley. He combines his academic background with a talent for storytelling, making complex scientific discoveries engaging and accessible. His work highlights the innovators behind the ideas, bringing readers closer to the people driving progress.