Scientists discover how your brain converts sounds into actions

Researchers have taken us a step closer to unravelling the mystery of how the brain translates perceptions into actions.

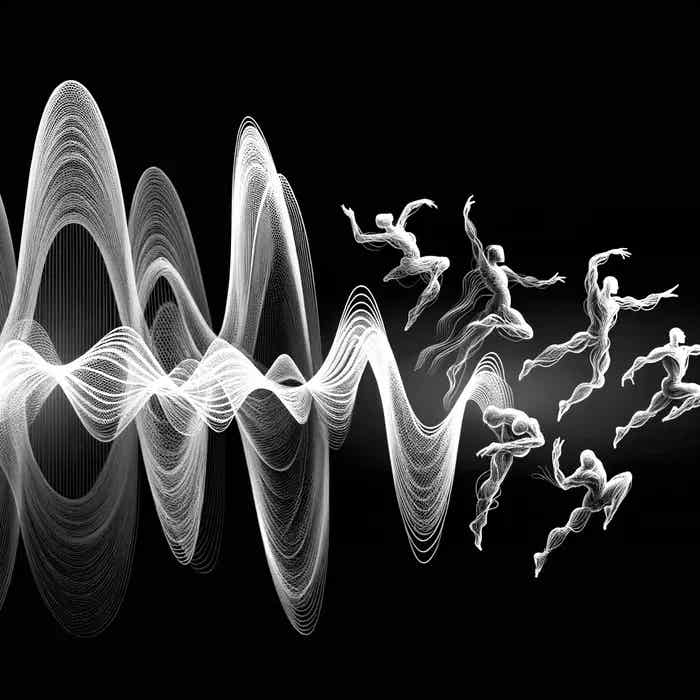

Abstract representation of the brain converting sound stimuli into movements (CREDIT: Hedi Young)

You hear a phone ring or a dog bark. Is it yours or someone else’s? Footsteps in the night — is it your child or an intruder? Friend or foe? Your decision shapes your next move. Researchers at the Champalimaud Foundation have delved into what might be occurring in our brains during such moments, bringing us closer to understanding how our brain translates perceptions into actions.

Each day, you make countless decisions based on sounds without a second thought. But what exactly happens in your brain during these instances? A new study from the Renart Lab, published in Current Biology, explores this. Their findings deepen our understanding of how sensory information and behavioral choices intertwine within the cortex — the brain’s outer layer responsible for conscious perception.

The cortex has regions handling different functions: sensory areas process environmental information, while motor areas manage actions. Surprisingly, signals related to future actions appear in sensory regions, too. What are movement-related signals doing in sensory processing areas? When and where do these signals emerge? Exploring these questions could clarify the origin and role of these perplexing signals, and how they drive decisions.

To answer these questions, researchers devised a task for mice. Postdoc Raphael Steinfeld, the study’s lead author, explains: “To understand what signals related to future actions might be doing in sensory areas, we considered the task carefully. Previous studies often used 'Go-NoGo' tasks, where animals report their choice by either acting or staying still, depending on the stimulus.

This setup, however, mixes up signals linked to specific movements with those related to general movement. To isolate signals for specific actions, we trained mice to decide between two actions. They had to determine if a sound was high or low compared to a set threshold and report their decision by licking one of two spouts, left or right.”

However, this wasn't enough. “Mice quickly learn this task, often responding as soon as they hear the sound,” Steinfeld continues. “To separate brain activity related to the sound from that related to the response, we introduced a critical half-second delay. During this interval, the mice had to withhold their decision.

This delay allowed us to temporally separate brain activity linked to the stimulus from that linked to the choice, and track how movement-related neural signals unfolded over time from the initial sensory input.”

Related Stories

“To dissect neural representations of stimulus and choice, it was also important to design an experiment challenging enough to allow the mice to make mistakes. A 100% success rate would blur the distinction between stimulus and choice, as each stimulus would always elicit the same response. By creating the potential for errors, we could distinguish between the neural encoding of the sound and the decisions made.”

For instance, in cases where the mice heard the same tone but made different decisions (correct or incorrect), researchers could examine whether a neuron’s activity varied between the two actions. If so, it would indicate that the neuron encoded information about the choice.

After six months of rigorous training, the researchers could finally begin recording neural activity in mice as they performed the task. They focused on the auditory cortex, the part of the cortex responsible for processing what you hear, which they had already shown was required for the task.

“The cortex of mice and humans is composed of six layers, each with specialized functions and distinct connections to other brain regions,” explains Alfonso Renart, principal investigator and the study’s senior author. “Given that certain layers typically receive sensory information from brain regions, while others send input to motor centers, we simultaneously recorded activity across the layers of the auditory cortex — for the first time in a task like ours, in which sensory and motor signals could be cleanly separated.”

“We found that sensory- and choice-related signals displayed distinct spatial and temporal patterns,” Renart continues. “Signals related to sound detection appeared quickly but faded fast, vanishing around 400 milliseconds after the sound was presented, and were distributed broadly across all cortical layers. In contrast, choice-related signals, which indicate the movement the mouse is about to make, emerged later, before the decision was executed, and were concentrated in the cortex’s deeper layers.”

Despite the temporal separation between stimulus and choice activity, further analysis revealed an intriguing connection: neurons that responded to a specific sound frequency also tended to be more active for the actions associated with those sounds.

As Steinfeld explains, “For instance, a neuron that reacts to high frequencies might activate more for a rightward lick in one mouse and a leftward lick in another, depending on how each was trained, since we switched the sound-action contingency. This variability across different animals shows that the activity isn’t hardwired but adapts through experience. These neurons learn to increase their activity for whatever action is appropriate based on their preferred sound frequency.”

So, what might the origin of these choice signals in the auditory cortex be? “Interestingly,” notes Renart, “the early sensory signals in the auditory cortex don’t seem to predict the mice’s eventual choice, and the choice signals emerge significantly later. This suggests that the sensory signals in the auditory cortex don’t directly cause the mice’s actions, and that the choice signals we observe are likely computed elsewhere in higher brain regions involved in planning or executing movements, which then send their feedback to the auditory cortex.”

But if these movement signals don’t dictate actions, what role could they play? Perhaps they serve mainly to integrate and relay information. For instance, these signals could adjust the brain’s perception to align with an unfolding decision, enhancing the stability of what you perceive. Alternatively, they could prime the brain for the expected sensory outcomes of actions, like the noise made by moving, ensuring your sensory experiences match your movements.

Yet, these hypotheses remain to be verified. “One might wonder, if the sensory signals of the auditory cortex don’t directly inform choices, and the choice signals we observe there aren’t actually produced by it, then what exactly is the purpose of the auditory cortex?” Renart muses. “We could speculate that the auditory cortex is more concerned with constructing a conscious experience of sound than with sensory-motor transformation, but that’s a story for another day.”

Still, a causal role cannot be ruled out, particularly since the deeper layers of the auditory cortex transmit information to the posterior striatum, part of the brain’s control center for habits and movements. Future studies will aim to pinpoint the precise origins of these movement signals and whether they are indeed causal to behavior. For now, you can add another piece to the puzzle of how brains convert perception to action, and understand the internal mechanisms at work when you next hear footsteps in the night.

Note: Materials provided above by The Brighter Side of News. Content may be edited for style and length.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News' newsletter.

Joshua Shavit

Science & Technology Writer | AI and Robotics Reporter

Joshua Shavit is a Los Angeles-based science and technology writer with a passion for exploring the breakthroughs shaping the future. As a contributor to The Brighter Side of News, he focuses on positive and transformative advancements in AI, technology, physics, engineering, robotics and space science. Joshua is currently working towards a Bachelor of Science in Business Administration at the University of California, Berkeley. He combines his academic background with a talent for storytelling, making complex scientific discoveries engaging and accessible. His work highlights the innovators behind the ideas, bringing readers closer to the people driving progress.