Researchers discover new link between gut bacteria and Alzheimer’s disease

A new study links gut bacteria Klebsiella pneumoniae to Alzheimer’s risk, suggesting a role of hospital infections in neurodegeneration.

Alzheimer’s disease (AD), the most prevalent form of dementia, manifests through complex brain changes. (CREDIT: CC BY-SA 3.0)

Dementia, a cognitive disorder affecting memory, reasoning, and social abilities, is currently experienced by an estimated 50 million people worldwide. Alarming projections suggest this figure may triple by 2050.

Alzheimer’s disease (AD), the most prevalent form of dementia, manifests through complex brain changes, including neurodegeneration, loss of neural connections, and the buildup of amyloid-β plaques and neurofibrillary tangles. However, chronic neuroinflammation has emerged as a critical factor in the development and acceleration of Alzheimer’s symptoms.

While genetic, environmental, and lifestyle factors contribute to AD risk, recent studies point to infections as a key driver, potentially amplifying AD incidence by triggering systemic inflammation.

Findings from large cohort studies underscore that patients hospitalized with infections may face up to a 1.7-fold higher risk of developing dementia. Health care-associated infections (HAIs), acquired during hospital stays, compound this issue and are ranked among the ten leading causes of death in the U.S., affecting up to 9.3% of patients hospitalized.

The challenge of controlling HAIs is further complicated by the rise of antibiotic-resistant bacteria, particularly concerning among elderly patients with weakened immune systems and disrupted gut microbiomes due to prolonged antibiotic treatments. Antibiotics, while essential for combating infections, also degrade beneficial gut bacteria, disrupting the body’s initial defenses and elevating the risk of severe gut infections.

Related Stories

An estimated 60% to 80% of health care patients receive at least one antibiotic, leading to long-term impacts on gut microbial health, including the rise of antibiotic-resistant organisms that can remain in the gut, traverse the gut lining, and potentially contribute to HAIs in other parts of the body.

One bacterium, Klebsiella pneumoniae, stands out for its role in HAIs. Known to affect the respiratory, intestinal, and urinary tracts, this bacterium often begins its infection process in the gastrointestinal (GI) tract before spreading. Widespread antibiotic usage has led K. pneumoniae to develop considerable resistance, allowing it to proliferate in the GI tract and subsequently invade other body systems.

Once K. pneumoniae breaks through the intestinal mucosal barrier, it can enter the bloodstream, migrate to different organs, and in some cases, lead to life-threatening conditions like bacterial meningitis—a severe infection of the membranes surrounding the brain and spinal cord.

The neuroinflammation caused by bacterial meningitis can permanently damage neuronal circuits, with survivors often facing long-term cognitive effects, including memory impairment and dementia.

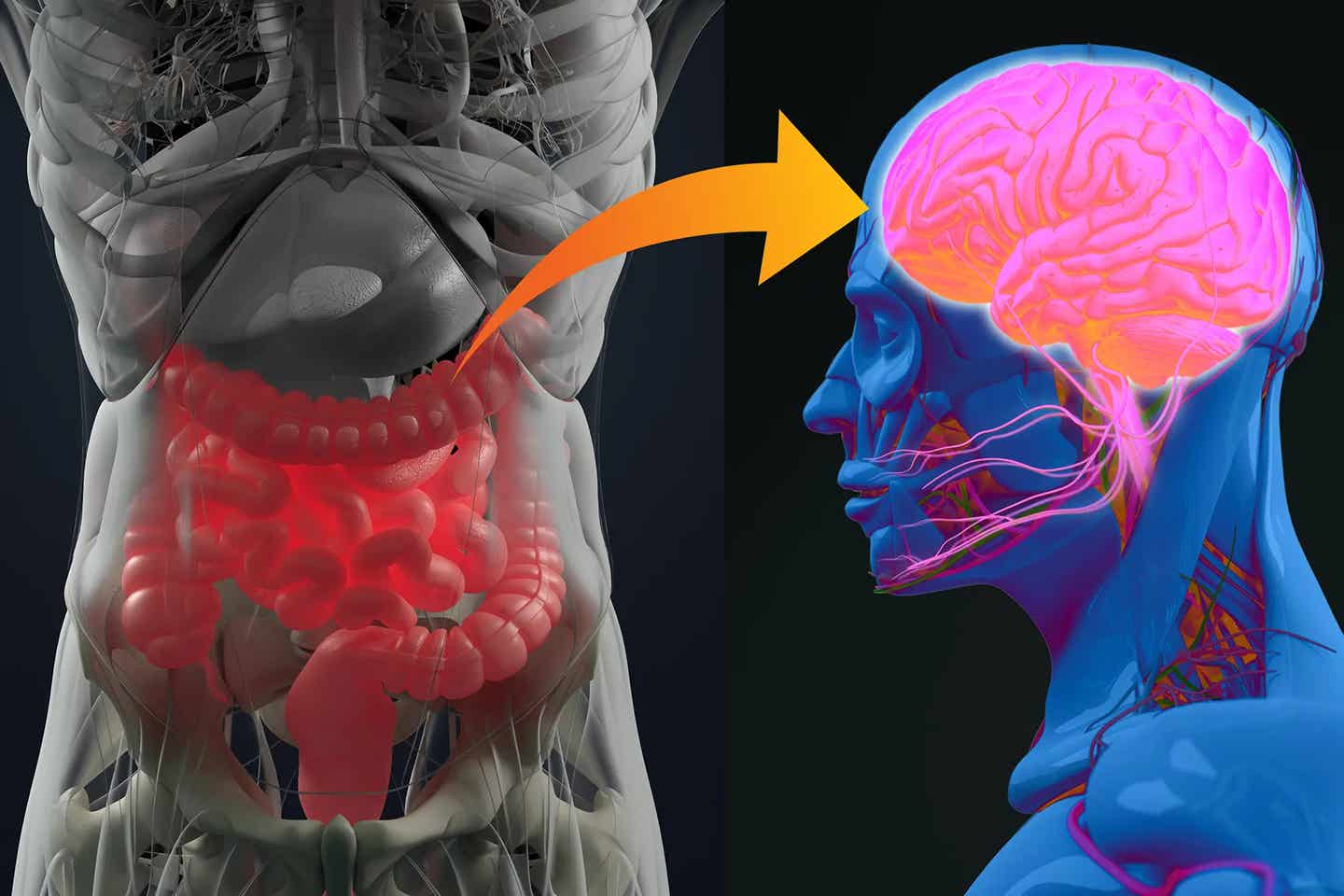

In light of these concerns, researchers are investigating how K. pneumoniae infections might specifically affect brain health. A pivotal study from Florida State University’s Gut Biome Lab suggests that this bacterium may travel from the gut to the brain, exacerbating neuroinflammation and accelerating the progression of neurodegenerative conditions such as Alzheimer’s disease. The researchers observed that once K. pneumoniae enters the bloodstream, it can reach the brain, where it may initiate inflammatory responses that resemble Alzheimer’s pathology.

“Hospitalizations and ICU stays, combined with antibiotic exposure, may lead to a further decline in microbiome diversity that leaves older adults at high risk not only for digestive issues but also for extra-intestinal pathologies such as neurodegenerative disorders through a dysregulation of the gut-brain axis,” said Ravinder Nagpal, an assistant professor in the FSU College of Education, Health, and Human Sciences and director of the Gut Biome Lab.

This research marks the first study to establish a direct connection between K. pneumoniae infections and Alzheimer’s-related brain changes. It also highlights the pressing need to explore how infections might act as a catalyst for Alzheimer’s, potentially opening pathways for preventive and therapeutic interventions for those particularly vulnerable, such as the elderly or sepsis survivors.

In their study, Nagpal and his team used a preclinical mouse model to examine how antibiotics impact the gut microbiome and facilitate K. pneumoniae growth. They found that antibiotics deplete beneficial gut bacteria, creating an environment that favors the proliferation of K. pneumoniae.

Under these conditions, the bacterium not only thrives in the gut but can also move into the bloodstream by breaching the gut lining and eventually reach the brain. This gut-brain translocation initiates neuroinflammation and neurocognitive decline, which mirrors aspects of Alzheimer’s disease.

“Hospital-acquired and septic infections are one of the risk factors that may increase the predispositions to future neuroinflammatory and neurocognitive impairments, especially in older adults,” Nagpal added, underscoring the long-term consequences of these infections.

The research emphasizes the urgent need to explore innovative therapeutic strategies that extend beyond traditional AD treatments, such as amyloid and tau-targeted therapies. While these therapies have been the main focus of AD research, addressing the role of infectious agents could open doors to novel prevention and treatment methods aimed at protecting cognitive health. In particular, managing hospital-acquired infections and preserving microbiome health among aging patients could serve as a pivotal step in reducing neurodegenerative risks.

As dementia rates continue to climb, addressing the role of HAIs and their link to Alzheimer’s disease becomes increasingly critical. The FSU study underlines that preserving gut health through careful antibiotic use and improving hospital infection control could have far-reaching implications, potentially reducing the burden of neurodegenerative diseases in older adults.

For those at heightened risk of AD, maintaining a diverse gut microbiome may prove essential in safeguarding cognitive health, highlighting the importance of targeted strategies in health care to mitigate the rising tide of Alzheimer’s disease.

Note: Materials provided above by The Brighter Side of News. Content may be edited for style and length.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News' newsletter.

Joshua Shavit

Science & Technology Writer | AI and Robotics Reporter

Joshua Shavit is a Los Angeles-based science and technology writer with a passion for exploring the breakthroughs shaping the future. As a contributor to The Brighter Side of News, he focuses on positive and transformative advancements in AI, technology, physics, engineering, robotics and space science. Joshua is currently working towards a Bachelor of Science in Business Administration at the University of California, Berkeley. He combines his academic background with a talent for storytelling, making complex scientific discoveries engaging and accessible. His work highlights the innovators behind the ideas, bringing readers closer to the people driving progress.