Scientists find major link between gut health and arthritis

Scientists discover how gut bacteria trigger arthritis by breaking down tryptophan into inflammatory byproducts, paving the way for new treatments.

Because what you eat shapes your gut bacteria, changing your diet could help lower inflammation linked to arthritis. (CREDIT: CC BY-SA 4.0)

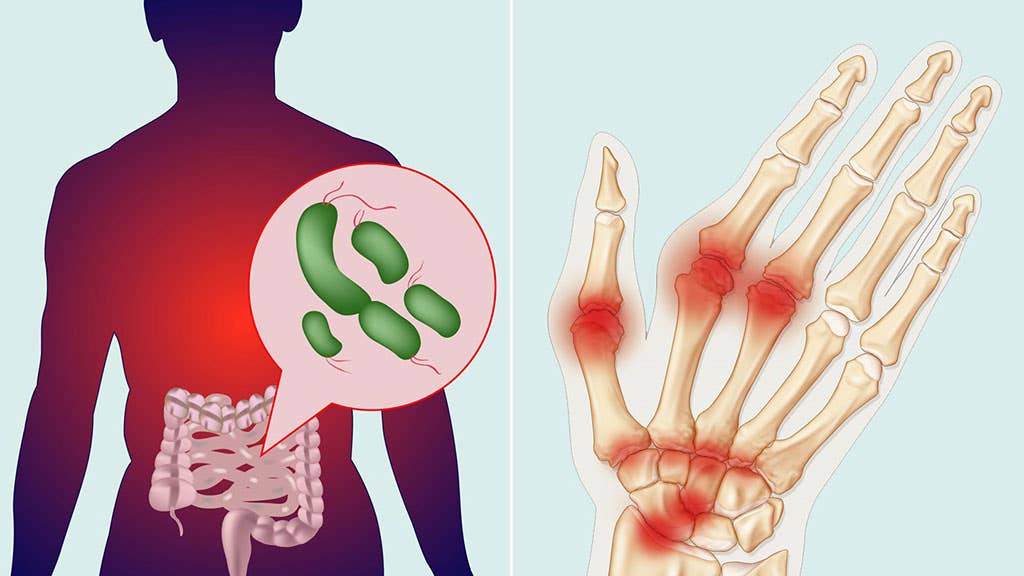

Rheumatoid arthritis and spondyloarthritis are long-lasting inflammatory diseases that gradually wear down joints. While genes contribute to these disorders, they don’t tell the whole story. Environmental factors—especially smoking—raise the risk in people who are already genetically at risk. Now, scientists are turning their attention to a less obvious culprit: the trillions of bacteria in your gut.

Researchers have found that many people with these conditions have gut microbiomes that are off balance. This state, called dysbiosis, may play a central role in triggering inflammation. For rheumatoid arthritis, scientists support what’s known as the “mucosal origins hypothesis.” This idea holds that immune dysfunction may first appear in the gut or other mucosal surfaces, then spread to the joints.

Microbes in Your Gut Could Trigger Arthritis

Evidence continues to build for a years-long “preclinical” phase in RA, where warning signs quietly emerge. During this stage, which can last 5 to 10 years, the gut may show early signs of imbalance, like the presence of harmful bacteria and high levels of inflammation.

Researchers have also detected specific autoantibodies in the blood before any joint damage occurs. One type of bacteria, Subdoligranulum, has drawn attention for its possible role in setting off this process.

Spondyloarthritis seems to follow a similar path. About 50% of patients with SpA show signs of microscopic gut inflammation. This has led to growing interest in what scientists call the “gut-joint axis.” The theory suggests that immune problems in the digestive tract may eventually spark joint inflammation. While the exact process remains a mystery, the link between gut health and joint disease appears stronger than ever.

Tryptophan’s Secret Pathway Revealed Through Indole

A recent study from the University of Colorado adds fresh insight into this connection. Led by Dr. Kristine Kuhn, the research team focused on tryptophan, an essential amino acid you get from food. Tryptophan plays a key role in building proteins, supporting muscles, and producing brain chemicals like serotonin. What intrigued the researchers was how gut bacteria process tryptophan and how that breakdown might fuel inflammation.

Related Stories

By studying the way bacteria in the gut interact with tryptophan, the researchers uncovered a potential chain reaction leading to arthritis. They found that certain bacterial byproducts could affect the immune system in ways that promote joint damage. Dr. Kuhn’s findings bring scientists one step closer to understanding how gut microbes might not just reflect disease—but help cause it.

The study, published in the Journal of Clinical Investigation, found that when gut bacteria break down tryptophan, they produce inflammatory byproducts such as indole. In experiments with mice, those given antibiotics to remove their gut bacteria did not develop arthritis or produce indole.

Similarly, when mice were fed a diet low in tryptophan, they also remained free of arthritis. These findings suggest that microbial breakdown of tryptophan into indole plays a critical role in triggering the disease.

Further analysis revealed that indole increases inflammatory T-cells while reducing regulatory T-cells, which normally help maintain immune balance. Indole also enhances the production of inflammatory antibodies, worsening immune system attacks on the joints.

Potential for New Treatments

Understanding the role of tryptophan metabolism in arthritis opens new possibilities for treatment. Kuhn and her colleagues propose that blocking indole production or shifting tryptophan metabolism toward anti-inflammatory pathways could provide relief.

Since diet affects gut bacteria, dietary interventions might help reduce inflammation. Research suggests that fiber-rich, plant-based diets, such as the Mediterranean diet, promote a gut microbiome that favors anti-inflammatory tryptophan metabolism.

Beyond dietary changes, the Division of Rheumatology at the University of Colorado is working on ways to identify people at high risk for RA. By detecting specific blood markers, researchers hope to develop early interventions that could prevent or slow the disease.

Although much work remains, this research could lead to new therapeutic approaches that mitigate arthritis before irreversible joint damage occurs.

The connection between gut bacteria and inflammatory arthritis highlights the complex interplay between the microbiome and the immune system.

By targeting this pathway, scientists may be able to develop treatments that not only manage symptoms but also prevent disease onset altogether.

Symptoms of Rheumatoid Arthritis

According to the Mayo Clinic, signs and symptoms of rheumatoid arthritis may include:

- Tender, warm, swollen joints

- Joint stiffness that is usually worse in the mornings and after inactivity

- Fatigue, fever and loss of appetite

Early rheumatoid arthritis tends to affect your smaller joints first — particularly the joints that attach your fingers to your hands and your toes to your feet.

As the disease progresses, symptoms often spread to the wrists, knees, ankles, elbows, hips and shoulders. In most cases, symptoms occur in the same joints on both sides of your body.

About 40% of people who have rheumatoid arthritis also experience signs and symptoms that don't involve the joints. Areas that may be affected include:

- Skin

- Eyes

- Lungs

- Heart

- Kidneys

- Salivary glands

- Nerve tissue

- Bone marrow

- Blood vessels

Rheumatoid arthritis signs and symptoms may vary in severity and may even come and go. Periods of increased disease activity, called flares, alternate with periods of relative remission — when the swelling and pain fade or disappear. Over time, rheumatoid arthritis can cause joints to deform and shift out of place.

Note: Materials provided above by The Brighter Side of News. Content may be edited for style and length.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News' newsletter.