Astronomers discover what’s at the center of a black hole

Researchers combined quantum computing with machine learning to uncover fresh insights into the fundamental properties of black holes.

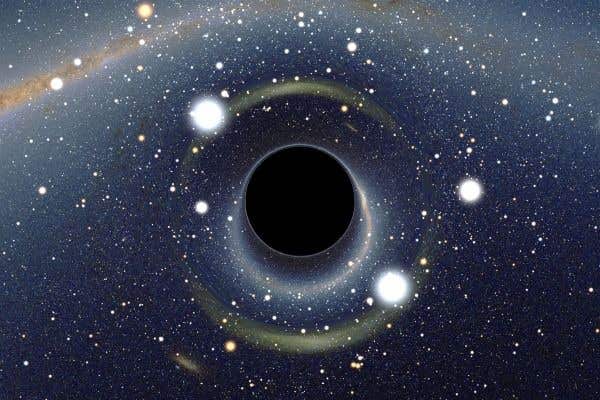

What lies at the heart of a black hole has puzzled physicists for decades. (CREDIT: Alain R. | Wikimedia Commons)

What lies at the heart of a black hole has puzzled physicists for decades. Now, a team led by physicist Enrico Rinaldi has taken a bold approach to the mystery. By using quantum computing and machine learning, they’ve begun to map the quantum state of a complex matrix model. This method, Rinaldi says, is helping researchers understand black holes in ways not possible before.

Their work is grounded in the holographic principle—an idea suggesting two seemingly separate realms of physics are actually linked. One describes gravity in a space with three dimensions, while the other focuses on particles existing on a flat, two-dimensional surface. Though these models differ in dimension, they are believed to describe the same underlying reality.

Black Hole Theories

In this view, a black hole’s mass distorts space-time, creating a deep gravitational well. That pull stretches out across three dimensions, yet it connects with particles on a flat, two-dimensional plane. From far away, the black hole may look like a projection made only of particles. But beneath that illusion lies a tightly woven connection between space, time, and matter.

Some researchers think this holographic idea could apply to the entire universe. If true, space itself might be a projection from a more basic set of quantum laws.

“In Einstein’s General Relativity, space-time exists but there are no particles,” Rinaldi explains. “In the Standard Model, particles exist, but there’s no gravity.” Finding a bridge between the two remains one of physics’ biggest unsolved problems.

To chip away at that problem, Rinaldi and his team used quantum computers and deep learning to study matrix models. These are mathematical systems thought to capture both particles and gravity within a single structure. Their aim was to find the matrix’s ground state—the lowest possible energy level—which may hold clues about the nature of space and time.

Published in PRX Quantum, the team's findings mark a step forward in testing the holographic duality. By blending quantum hardware with advanced algorithms, they’re building tools to explore deep questions about the universe’s structure. The results don’t fully solve the mystery of black holes—but they’re pushing the limits of how we understand them.

Related Stories

The use of quantum matrix models represents the particle theory. According to holographic duality, the mathematical events that occur in a system representing particle theory can also impact a system representing gravity. Thus, by solving a quantum matrix model, one could gain insights into gravity-related phenomena.

Rinaldi and his colleagues have utilized two matrix models, which are relatively uncomplicated to solve through conventional means but possess all of the attributes of more complex matrix models employed to describe black holes using holographic duality.

“We hope that by understanding the properties of this particle theory through the numerical experiments, we understand something about gravity,” adds Rinaldi. “Unfortunately it’s still not easy to solve the particle theories. And that’s where the computers can help us.”

In string theory, objects are represented by numerical matrix models, where one-dimensional strings correspond to particles in particle theory. The focus of researchers is to determine the specific arrangement of particles in the ground state, the lowest energy state of the system, by solving these matrix models. Unless something is added to the system that causes it to be perturbed, it remains unchanged in its natural state.

“It’s really important to understand what this ground state looks like, because then you can create things from it,” Rinaldi says. “So for a material, knowing the ground state is like knowing, for example, if it’s a conductor, or if it’s a super conductor, or if it’s really strong, or if it’s weak. But finding this ground state among all the possible states is quite a difficult task. That’s why we are using these numerical methods.”

According to Rinaldi, the numbers in matrix models can be thought of as grains of sand. When the sand is level, it corresponds to the ground state of the model. But if there are ripples in the sand, you need to find a way to smooth them out. To tackle this problem, the researchers resorted to quantum circuits.

These circuits are depicted as wires, and each wire is associated with a qubit, a quantum information bit. Gates, which are quantum operations that dictate how information flows through the wires, are placed on top of the wires.

“You can read them as music, going from left to right,” the author adds. “If you read it as music, you’re basically transforming the qubits from the beginning into something new each step. But you don’t know which operations you should do as you go along, which notes to play. The shaking process will tweak all these gates to make them take the correct form such that at the end of the entire process, you reach the ground state. So you have all this music, and if you play it right, at the end, you have the ground state.”

Rinaldi and colleagues established the mathematical representation of the quantum state of their matrix model, which they referred to as the quantum wave function. Subsequently, they employed a unique neural network to determine the ground state of the matrix, which is the state with the lowest energy level.

To achieve this, the neural network's parameters underwent an iterative optimization process, aimed at leveling all the grains in the bucket of sand, until the matrix's ground state was found.

The researchers were successful in determining the ground state of the two matrix models using both methods. However, the quantum circuits were constrained by the limited number of qubits available in current quantum hardware. With only a few dozen qubits at their disposal, increasing the complexity of the circuit would become prohibitively expensive, much like adding too many notes to a sheet of music would make it more difficult to play accurately.

“Other methods people typically use can find the energy of the ground state but not the entire structure of the wave function,” Rinaldi said. “We have shown how to get the full information about the ground state using these new emerging technologies, quantum computers and deep learning."

“Because these matrices are one possible representation for a special type of black hole, if we know how the matrices are arranged and what their properties are, we can know, for example, what a black hole looks like on the inside. What is on the event horizon for a black hole? Where does it come from? Answering these questions would be a step towards realizing a quantum theory of gravity.”

According to Rinaldi, the findings serve as a crucial milestone for forthcoming research on quantum and machine learning algorithms. These algorithms can be applied by scholars to investigate quantum gravity through the concept of holographic duality.

In the next phase, Rinaldi, together with Nori and Hanada, is examining how these algorithms' outcomes can expand to more extensive matrices and how immune they are to the influence of "noisy" effects, which can lead to inaccuracies.

Major components of black holes

A black hole consists of several key components, each contributing to its complex nature:

Singularity:

At the very center of a black hole lies the singularity, a point where gravity is so intense that spacetime is infinitely curved, and the laws of physics as we know them break down. It is thought to be an infinitely small, dense point.

Event Horizon:

The event horizon is the "point of no return." Once anything, including light, crosses this boundary, it can no longer escape the black hole's gravitational pull. The event horizon defines the black hole's size and is often the most recognizable feature.

Photon Sphere:

Just outside the event horizon, the photon sphere is a region where light can orbit the black hole due to its extreme gravity. Photons (light particles) can temporarily circle the black hole before either escaping or being pulled in.

Accretion Disk:

Many black holes are surrounded by an accretion disk, a rotating ring of gas, dust, and other matter spiraling toward the event horizon. The intense friction in the disk heats the material, causing it to glow and emit radiation, often making black holes detectable.

Doppler Beaming (Relativistic Beaming):

Doppler beaming occurs when material, such as jets or particles in the accretion disk, moves at relativistic speeds (close to the speed of light). As the material moves toward the observer, the radiation it emits is compressed, leading to a boost in brightness and intensity—this is the "beaming" effect. Conversely, material moving away from the observer appears dimmer.

Ergosphere (for rotating black holes):

In rotating (Kerr) black holes, there is an additional region called the ergosphere. It lies just outside the event horizon and is where spacetime is dragged along with the black hole's rotation. Objects within the ergosphere can still escape the black hole’s gravity if they gain enough energy.

Jets:

Some black holes, particularly those in active galaxies, can eject powerful jets of charged particles along their rotational axis. These jets can travel vast distances into space and are caused by the magnetic fields generated by the accretion disk.

Each of these parts plays a role in shaping the behavior of black holes and their interactions with surrounding matter and spacetime.

Note: Materials provided above by The Brighter Side of News. Content may be edited for style and length.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News' newsletter.