Paralyzed man moves robotic arm with his mind

AI-powered BCI enables a paralyzed man to control a robotic arm for months, offering new hope for neuroprosthetic technology.

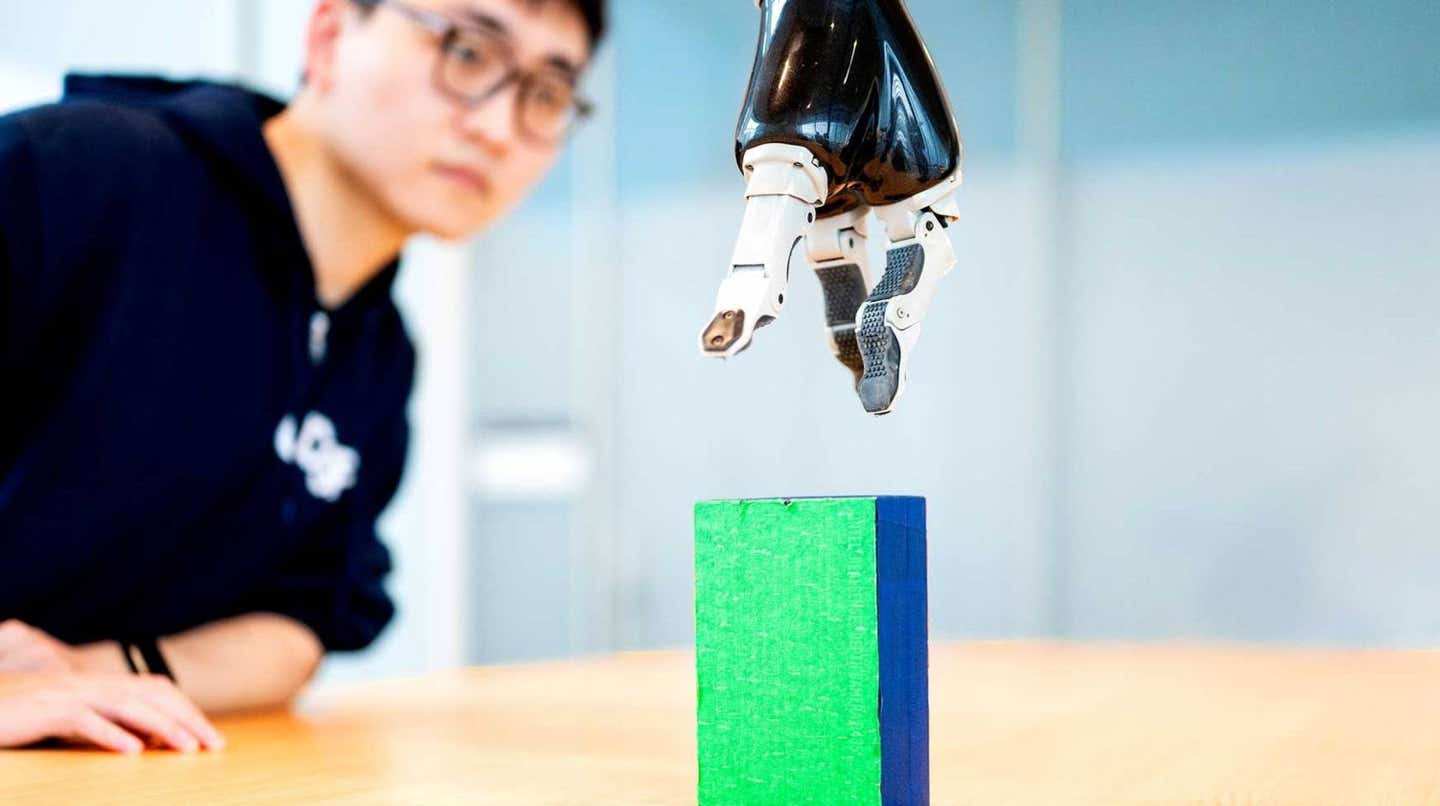

A breakthrough AI-powered brain-computer interface allowed a paralyzed man to control a robotic arm for months. (CREDIT: Noah Berger/UC San Francisco)

The human nervous system must balance stable motor control with adaptability for learning new movements. Brain activity forms a neural representation of these actions, a dynamic process that shifts over time.

Studies in animals show that these representations are not fixed but drift subtly with repeated behavior. While research in humans confirms distinct neural maps for simple movements, how these representations evolve over days remains unclear.

Tracking these changes requires high-precision tools. Researchers at UC San Francisco (UCSF) have leveraged brain-computer interfaces (BCIs) based on electrocorticography (ECoG) to investigate this neural plasticity. By implanting a sensor grid over the brain’s motor regions, they have mapped how imagined movements shape brain activity patterns.

This research has led to a breakthrough in neuroprosthetic control, enabling a paralyzed man to operate a robotic arm with unprecedented long-term stability. The team published their findings in the journal Cell.

A New Era of Brain-Computer Interfaces

BCIs translate brain signals into commands for external devices. However, past systems required frequent recalibration due to neural drift, making long-term use impractical.

The UCSF team solved this challenge by integrating artificial intelligence (AI) into the BCI. AI adapts to the subtle shifts in neural representations over time, allowing seamless device operation for months instead of days.

“This blending of learning between humans and AI is the next phase for these brain-computer interfaces,” said neurologist Karunesh Ganguly, MD, PhD. “It’s what we need to achieve sophisticated, lifelike function.”

Related Stories

The study participant, who had been paralyzed by a stroke, had sensors implanted on the surface of his brain. These sensors recorded neural activity as he imagined moving his hands, feet, or head.

The AI analyzed how his brain's movement representations changed each day. While the overall structure of these patterns remained stable, their locations shifted slightly. The AI compensated for this drift, ensuring consistent function without frequent recalibration.

Training the Mind to Move Again

The participant first trained the AI model by imagining simple hand and finger movements over two weeks. These mental exercises refined the system’s ability to decode his intentions. Initially, control over the robotic arm lacked precision. To improve accuracy, researchers introduced virtual training.

Using a simulated robotic arm, the participant practiced guiding the device while receiving feedback on his imagined movements. This virtual environment allowed him to refine his mental commands before transitioning to the physical robotic arm. With just a few practice sessions, he successfully transferred these skills to the real world.

He demonstrated impressive control, picking up blocks, turning them, and moving them to new locations. He even performed complex tasks like opening a cabinet, retrieving a cup, and positioning it under a water dispenser.

Long-Term Stability and Future Applications

Traditional BCIs degrade in performance over time, requiring frequent recalibration. In contrast, the UCSF system maintained functionality for seven months, needing only brief tune-ups to accommodate neural drift. This stability marks a major step toward practical neuroprosthetic use outside of the lab.

For individuals with paralysis, regaining the ability to perform basic tasks—such as feeding themselves or grasping objects—could be life-changing. Researchers are now refining the AI models to improve speed and fluidity, with plans to test the system in a home environment.

“I’m very confident that we’ve learned how to build the system now, and that we can make this work,” said Ganguly.

With continued advancements, BCIs may soon offer individuals with paralysis a level of independence that was once unimaginable.

Note: Materials provided above by The Brighter Side of News. Content may be edited for style and length.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News' newsletter.

Joseph Shavit

Head Science News Writer | Communicating Innovation & Discovery

Based in Los Angeles, Joseph Shavit is an accomplished science journalist, head science news writer and co-founder at The Brighter Side of News, where he translates cutting-edge discoveries into compelling stories for a broad audience. With a strong background spanning science, business, product management, media leadership, and entrepreneurship, Joseph brings a unique perspective to science communication. His expertise allows him to uncover the intersection of technological advancements and market potential, shedding light on how groundbreaking research evolves into transformative products and industries.