Groundbreaking discovery rewrites the history of the Hun Empire

Genetic research uncovers surprising links between the Huns and Xiongnu elites, reshaping our understanding of their origins and legacy in Europe.

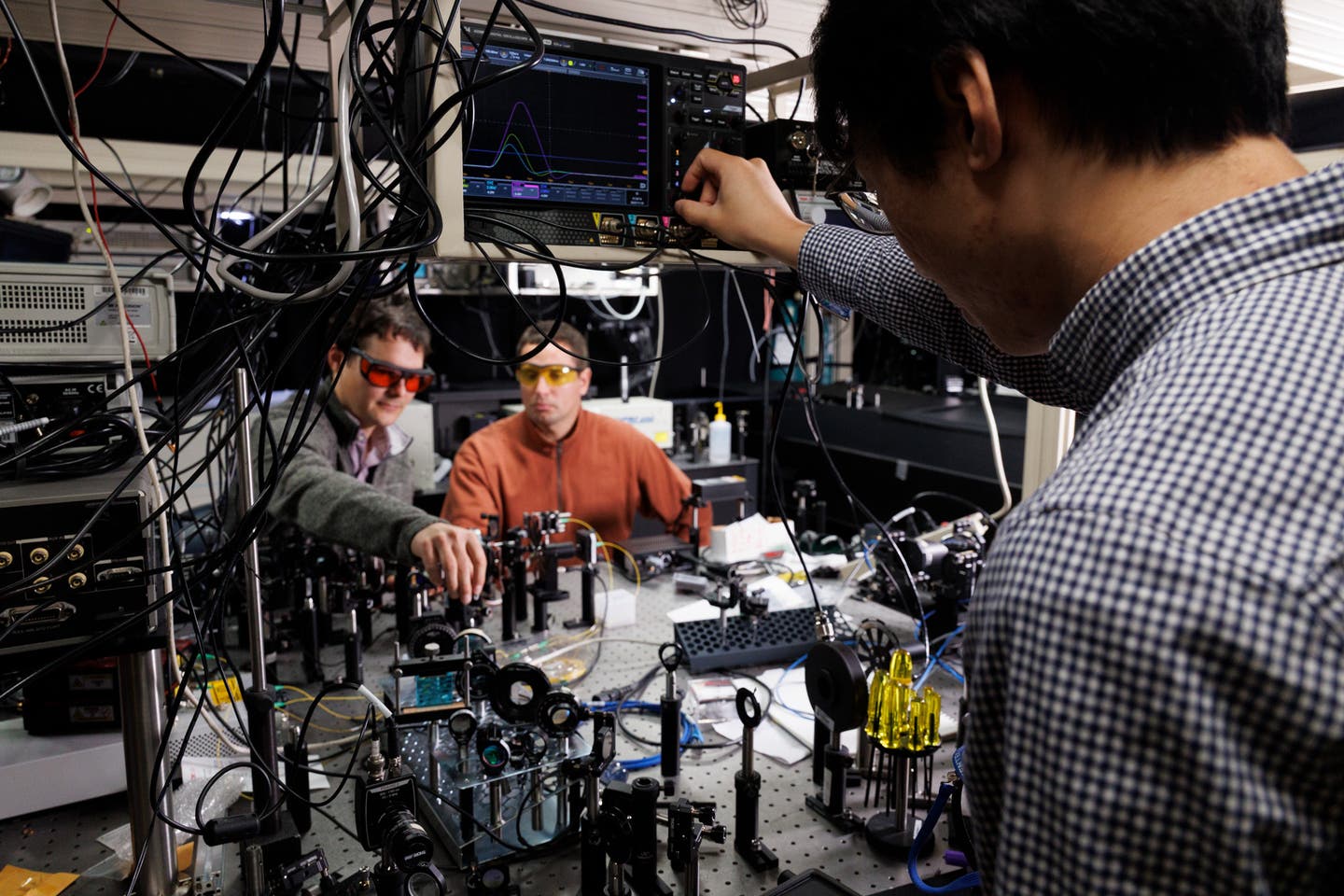

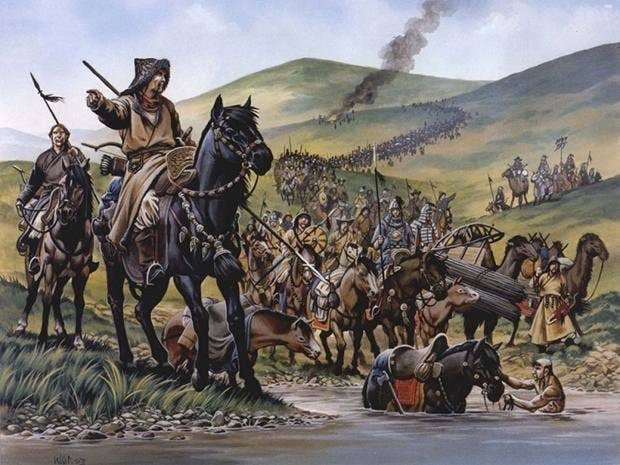

The Huns, once an unknown entity to the Roman world, arrived north of the Black Sea around 370 CE. (CREDIT: CC BY-SA 4.0)

In the late 4th century, Europe's political landscape changed dramatically with the sudden arrival of a fierce nomadic power. Emerging from the steppes, the Huns stormed into regions north of the Black Sea around 370 CE. Until their abrupt appearance, Romans knew little about these mysterious invaders.

The Huns quickly triggered chaos among established tribes such as the Goths and Alans. Their movements set off large-scale migrations, reshaping the Roman Empire profoundly. Roman historian Ammianus Marcellinus vividly described them as an unusual and formidable people, and even now, their precise origins spark intense debate among experts.

One leading theory connects the Huns to the Xiongnu, who dominated the Eurasian steppes from 200 BCE to about 100 CE. The Xiongnu empire stretched impressively from modern Mongolia deep into Inner Asia. After its collapse, smaller groups splintered and merged into other steppe cultures, complicating direct connections to the later Huns.

While intriguing linguistic similarities exist between "Xiongnu" and "Hun," clear historical evidence remains elusive. A significant 300-year gap and scarce written records challenge researchers seeking solid links between these two powerful steppe cultures. Despite this, archaeologists tirelessly search for clues that could bridge this historical puzzle.

Tracing Humanity’s Past in the Carpathian Basin

By the early 5th century, the Huns firmly controlled the Carpathian Basin, dismantling kingdoms like Sarmatia and seizing Roman territories. Their rapid conquest drastically altered archaeological records, marking periods of upheaval. Many settlements vanished or showed signs of violent destruction, though some communities endured, adapting successfully to Hunnic governance.

Archaeological discoveries from this period reveal a fascinating blend of cultural traditions. Items such as brooches, beads, combs, and distinctive polyhedral earrings combined Roman craftsmanship with steppe and Sarmatian designs. Particularly striking was the practice of artificial cranial deformation—elongating skulls—a tradition marking social prestige, prominently found in Hunnic burials.

Yet, unmistakable steppe customs were unevenly scattered across burial sites, emphasizing cultural complexity rather than uniformity. Grave alignments oriented north-south, sacrificial cauldrons, and equestrian gear highlight enduring links to earlier Eurasian nomadic practices. This rich tapestry of coexistence underscores the fluid and diverse cultural identity fostered during the Hunnic era.

Related Stories

- Ancient Bolivian temple discovery reveals secrets of lost Tiwanaku society

- Ancient wooden tools, from long before Homo sapiens emerged, discovered in China

- Ancient tooth fossil reveals humans have been getting high for over 4,000 years

After the fall of the Hunnic Empire in 454 CE, the Gepids took control of the eastern Carpathian Basin. Surprisingly, this transition did not erase Hunnic traditions. Smaller cemeteries continued to be used, and certain burial customs, like ACD, persisted into the Gepidic period. This suggests that the mixed population of the Hunnic era remained in the region, contributing to the area's evolving identity.

Unlocking the Genetic Legacy of the Huns

To better understand the Huns’ origins and their genetic impact on Europe, a team of researchers analyzed ancient DNA from 370 individuals spanning nearly 800 years. The study, part of the European Research Council’s HistoGenes project, included samples from sites across the Mongolian steppe, Central Asia, and the Carpathian Basin. Among these, 35 newly sequenced genomes provided key insights.

The findings revealed that, contrary to popular belief, the Huns did not introduce a large wave of steppe ancestry into Europe. Instead, the majority of the population in the Carpathian Basin remained genetically similar to earlier European inhabitants. However, a distinct subset of individuals—primarily those buried in “eastern-type” graves—displayed significant East Asian ancestry.

One of the study’s most intriguing discoveries came from identical-by-descent (IBD) analysis, which traces shared genetic segments. A handful of Hunnic-period individuals in Europe were found to have direct genetic links to high-ranking elites from the Xiongnu Empire. These connections included an individual buried in one of the most elaborate Xiongnu tombs ever discovered.

Guido Alberto Gnecchi-Ruscone, a researcher from the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, remarked, "It came as a surprise to discover that a few of these Hun-period individuals in Europe share IBD links with some of the highest-ranking imperial elite individuals from the late Xiongnu Empire."

Despite these connections, the broader genetic picture of the Huns was highly diverse. The study showed that rather than a single migrating population, the Huns in Europe represented a coalition of various groups, shaped by centuries of mobility and cultural exchange across Eurasia.

Zsófia Rácz of Eötvös Loránd University in Budapest explained, "DNA and archaeological evidence reveal a patchwork of ancestries, pointing to a complex process of mobility and interaction rather than a mass migration."

A Complex and Mixed Heritage

The genetic findings, published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), highlight key differences between the Huns and later steppe migrations, such as the Avars, who arrived in Europe two centuries later. The Avars migrated directly from East Asia after their empire fell to the Turks, retaining strong genetic ties to their homeland for centuries.

In contrast, the Huns’ journey to Europe was gradual, spanning multiple generations and involving intermixing with various populations along the way. Walter Pohl of the Austrian Academy of Sciences noted, "The ancestors of Attila’s Huns took many generations on their way westward and mixed with populations across Eurasia."

This research sheds new light on how ancient societies in the Carpathian Basin adapted to migration and conquest. While the Huns reshaped the political landscape, their genetic footprint outside of elite burials remained relatively small. Most people in the region retained European ancestry, incorporating steppe influences into their existing traditions rather than being replaced by a new population.

Zuzana Hofmanová of the Max Planck Institute summarized, "Although the Huns dramatically reshaped the political landscape, their actual genetic footprint—outside of certain elite burials—remains limited."

Johannes Krause, director of the Department of Archaeogenetics at the Max Planck Institute, emphasized the significance of this study in resolving long-standing historical debates. "From a broader perspective, the study underscores how cutting-edge genetic research, in combination with careful exploration of the archaeological and historical context, can resolve centuries-old debates about the composition and origin of past populations."

This research not only deepens our understanding of the Huns but also highlights the dynamic interactions that shaped Eurasian history. While the full story of their origins may never be completely unraveled, modern genetics is helping to connect the dots across centuries and continents, bringing new clarity to one of history’s most enigmatic peoples.

Note: Materials provided above by The Brighter Side of News. Content may be edited for style and length.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News' newsletter.