New discoveries show Neanderthals and Homo sapiens lived—and died—together

Burials at Tinshemet Cave show that ancient humans in the Middle East shared tools, rituals, and beliefs more than 100,000 years ago.

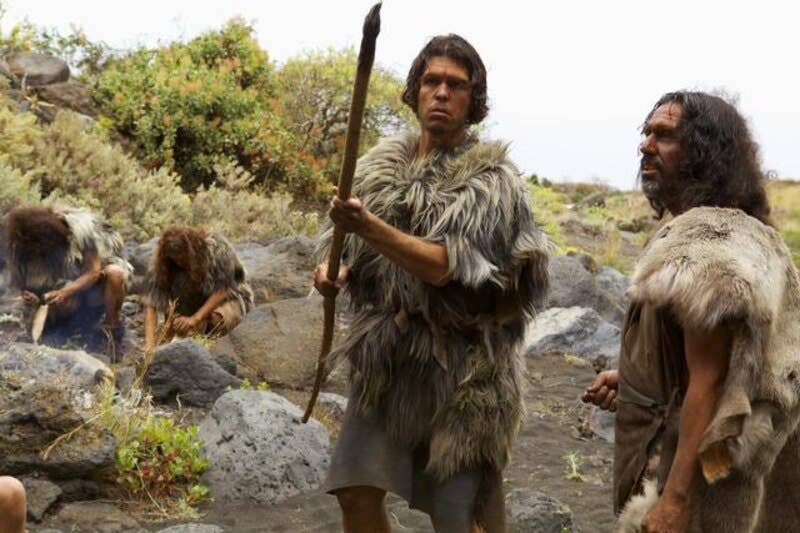

Burials at Tinshemet Cave reveal shared culture between early humans over 100,000 years ago in the Middle East. (CREDIT: La Crónica de Hoy)

In a time long before cities, farms, or even written words, early humans across the Levant were already shaping a complex story of connection, identity, and cultural exchange. Between 130,000 and 80,000 years ago, during a stretch of history known as the mid-Middle Paleolithic, this region in the Near East became a crucial meeting ground for different human groups—some who looked more like modern humans, others with traits resembling Neanderthals.

What researchers are now discovering is that these ancient people didn't just live near each other. They hunted together, shared technology, and even buried their dead in similar ways.

Recent discoveries at Tinshemet Cave in central Israel are helping to piece together a clearer view of this pivotal era. The cave, only about 10 kilometers from another important site at Nesher Ramla, has revealed one of the richest collections of human remains and cultural artifacts from this period.

For the first time in over 50 years, scientists have uncovered mid-Paleolithic human burials, complete with stone tools, animal bones, and chunks of red ochre—an iron-rich pigment used in burial rituals.

Findings, published in the journal Nature Human Behaviour, show that different hominin groups, including Homo sapiens and Neanderthal-like populations, weren't just existing in parallel. They were shaping one another's lives in meaningful ways.

A Shared Technological Language

One of the strongest pieces of evidence for this connection comes from stone tools. Across several major sites—Qafzeh, Skhul, Tabun, Nesher Ramla, and now Tinshemet—archaeologists have found strikingly similar lithic technology.

The most common technique, called the centripetal Levallois method, involves carefully shaping a stone core to produce sharp, flake-like tools. These tools appear across different regions and sites, regardless of the type of hominins that lived there.

Related Stories

This shared approach to tool-making suggests that knowledge was exchanged between groups. Researchers believe that human connections—through trade, travel, or intergroup cooperation—helped spread and preserve this technology. Rather than existing in isolation, these early humans were part of a broader cultural network that stretched across the southern Levant.

At Tinshemet Cave, the discovery of large lithic assemblages dominated by this technique aligns with similar findings at nearby Nesher Ramla and at Qafzeh, where earlier excavations uncovered seven burials with red ochre and grave goods. Even though the exact anatomical traits of the hominins at these sites vary—from modern Homo sapiens to archaic Neanderthal-like forms—their tools and practices speak a common cultural language.

Cultural Complexity Buried in Stone

What makes the Tinshemet site especially unique is not just the tools, but what they were buried with. In addition to weapons and work tools, the burials contained mineral pigments, particularly red ochre. This pigment might have been used to decorate bodies or objects during burial ceremonies, hinting at early symbolic thinking and ritual behavior.

The use of ochre and the intentional burial of the dead mark some of the earliest known examples of social and symbolic behavior in human history. These practices appear tens of thousands of years earlier in this region than anywhere else in the world.

Dr. Marion Prévost of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, who has been working at the site since 2017, sees this as a major sign of cultural evolution. “During the mid-MP, climatic improvements increased the region’s carrying capacity,” she says. “That likely led to population growth and more frequent contact between different Homo groups.”

This contact, she argues, helped build a shared sense of identity and community across genetically diverse populations.

Was Tinshemet a Cemetery?

The number and arrangement of burials at Tinshemet Cave have raised new questions. Could this have been a dedicated burial ground? The idea is bold, but the evidence is persuasive. The careful placement of bodies, the use of red ochre, and the presence of meaningful objects in the graves point to shared beliefs or rituals.

If these burials were not isolated acts but part of an established tradition, it would mean that these early humans had a deeper understanding of death—and possibly of an afterlife. Some scientists even suggest that this shows the beginning of religious thought, or at least a shared spiritual framework.

Professor Yossi Zaidner of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem describes Israel at that time as a “melting pot,” a place where different human groups came together and evolved side by side. “Our data show that human connections and population interactions have been fundamental in driving cultural and technological innovations throughout history,” he explains.

Professor Israel Hershkovitz of Tel Aviv University agrees. “These findings paint a picture of dynamic interactions shaped by both cooperation and competition,” he says. The archaeological record supports this view: while different groups may have competed for resources, they also learned from each other and even formed alliances.

Not Rivals, But Collaborators

So what were these interactions really like? Were Neanderthals and Homo sapiens friends, rivals, or something in between?

The evidence suggests they weren’t hostile strangers. Instead, they likely engaged in repeated exchanges that shaped their ways of life. These exchanges included how they made tools, how they hunted, and how they treated their dead. Over time, this led to what scientists call "cultural homogenization"—different groups began to behave in similar ways, even if they looked different or came from different genetic lines.

This idea is supported by the high diversity in human remains found across Levantine sites. At Qafzeh Cave, for example, fossils show a mix of traits, some more modern and others more archaic. This suggests interbreeding and gene flow between populations, possibly through long-term contact and shared living spaces.

Even at sites like Nesher Ramla, where the fossils resemble Neanderthals more than modern humans, the cultural artifacts—especially the tools—mirror those found at Tinshemet and Qafzeh. This further blurs the lines between groups and challenges the older view that these hominins lived separate lives.

A Crossroads in Human Evolution

The Levant during the mid-Middle Paleolithic wasn’t just another stop on the path of human migration. It was a place where something unique happened—where biology, culture, and environment came together to shape the future of our species.

This region served as a vital link between Africa, where Homo sapiens first appeared, and Eurasia, where Neanderthals and other human types lived. The geographic setting allowed for ongoing movement, contact, and interaction.

“Human connections, rather than isolation, were the main drivers of innovation,” says Dr. Prévost. And as more excavations continue at sites like Tinshemet Cave, this theory is gaining ground.

Each new layer of sediment and each new artifact tells a story of collaboration—of people who met, learned from each other, and left behind a shared legacy of culture and ideas.

Today, the discoveries at Tinshemet Cave are reshaping what scientists thought they knew about early human life. They remind us that history isn’t just a story of progress or competition. It’s also a story of connection.

As the dig continues, researchers hope to uncover more about how these ancient people lived, what they believed, and how their interactions gave rise to the complex societies we know today.

Note: The article above provided above by The Brighter Side of News.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News' newsletter.

Rebecca Shavit

Science & Technology Journalist | Innovation Storyteller

Based in Los Angeles, Rebecca Shavit is a dedicated science and technology journalist who writes for The Brighter Side of News, an online publication committed to highlighting positive and transformative stories from around the world. With a passion for uncovering groundbreaking discoveries and innovations, she brings to light the scientific advancements shaping a better future. Her reporting spans a wide range of topics, from cutting-edge medical breakthroughs and artificial intelligence to green technology and space exploration. With a keen ability to translate complex concepts into engaging and accessible stories, she makes science and innovation relatable to a broad audience.