Mitochondria may be the key to curing diabetes, study finds

Scientists have long observed that insulin-producing pancreatic β-cells in diabetic patients contain abnormal mitochondria.

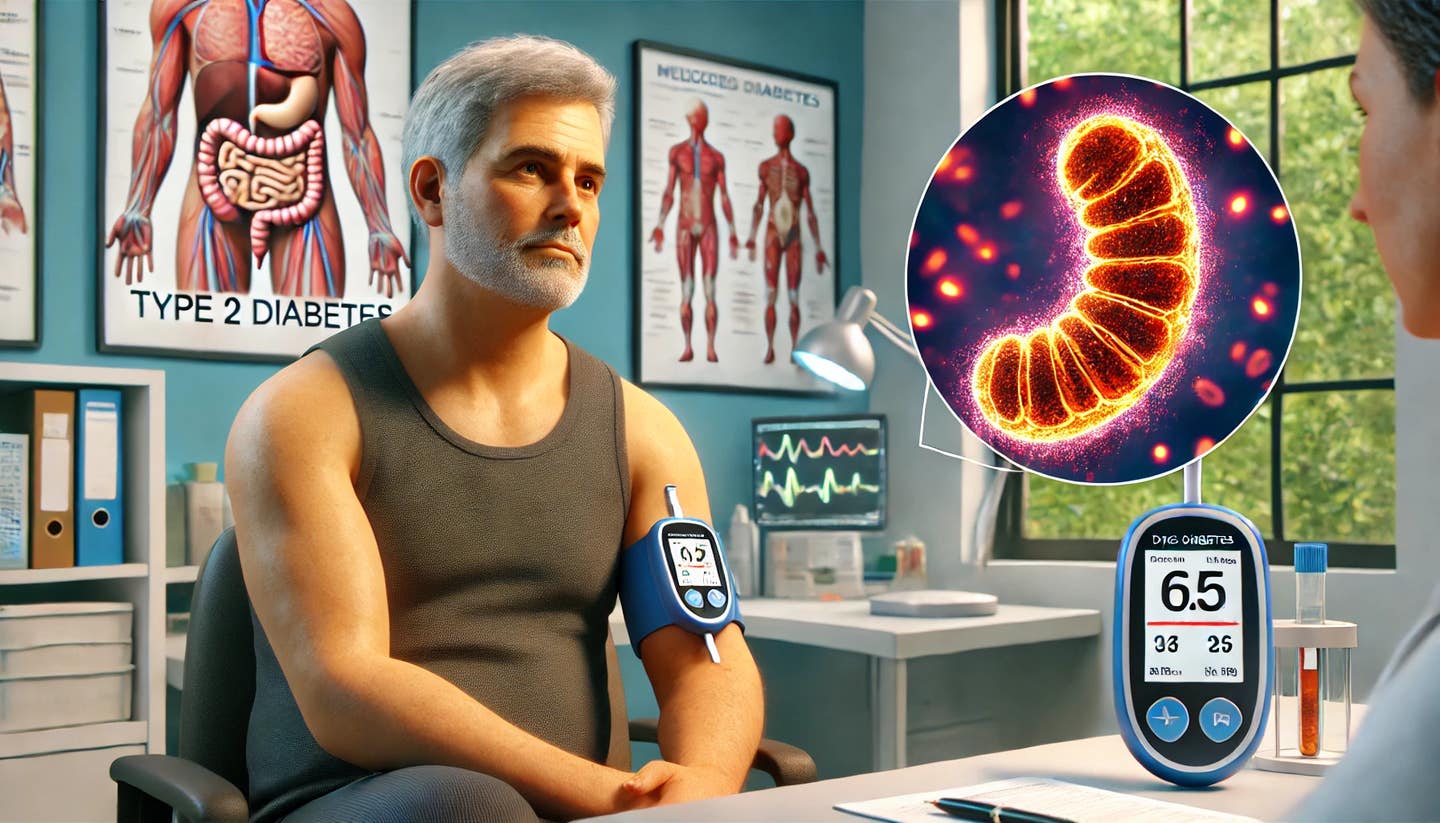

Mitochondria act as cellular power plants, converting nutrients into energy. Their dysfunction has been tied to metabolic disorders. (CREDIT: Image generated using DALL-E)

Mitochondria act as cellular power plants, converting nutrients into energy. When these structures fail, cells struggle to function properly. Their dysfunction has been tied to metabolic disorders, including type 2 diabetes, where the body either lacks sufficient insulin or cannot use it effectively to control blood sugar.

Scientists have long observed that insulin-producing pancreatic β-cells in diabetic patients contain abnormal mitochondria. However, previous studies have not fully explained how these defects impair β-cell function or contribute to disease progression.

A recent study in Science by researchers at the University of Michigan brings new clarity to this issue. Working with mice, the team discovered that mitochondrial defects activate a stress response that alters the development and function of β-cells. Their findings highlight a previously unknown mechanism that could be central to diabetes.

How Mitochondrial Dysfunction Changes Cellular Identity

Energy production is a key function of mitochondria, and defects in these structures can cause widespread metabolic disruptions. In type 2 diabetes, these failures extend beyond pancreatic β-cells, affecting muscle, fat, and liver tissues. Each of these plays a role in insulin regulation, and when they malfunction, blood sugar control weakens.

Scientists already know that β-cells in diabetic patients contain damaged mitochondria and struggle to generate energy. Similar issues appear in skeletal muscle, visceral fat, and liver cells, further complicating the body's ability to process insulin. Despite these observations, the molecular pathways that safeguard mitochondrial health remain poorly understood.

Led by Emily M. Walker, Ph.D., a research assistant professor of internal medicine, the study set out to uncover these mechanisms. The researchers focused on how mitochondria influence β-cell function at the molecular level, hoping to identify key factors that drive disease.

Related Stories

To do this, the researchers disrupted three key mitochondrial processes in mice: mitochondrial DNA integrity, mitochondrial recycling via mitophagy, and mitochondrial quality control mechanisms.

“In all three cases, the exact same stress response was turned on, which caused β-cells to become immature, stop making enough insulin, and essentially stop being β-cells,” Walker explained.

The study's results revealed that malfunctioning mitochondria send distress signals to the nucleus, ultimately altering the fate of the cell. These findings were further validated in human pancreatic islet cells.

Mitochondrial Dysfunction Affects More Than Just Pancreatic Cells

Since diabetes impacts multiple organs, the research team expanded their investigation beyond pancreatic β-cells. They examined liver cells and fat-storing cells in mice, expecting to find similar stress responses.

“Diabetes is a multi-system disease—you gain weight, your liver produces too much sugar, and your muscles are affected. That’s why we wanted to look at other tissues as well,” said Scott A. Soleimanpour, M.D., director of the Michigan Diabetes Research Center and senior author of the study.

The team found that liver and fat cells exhibited the same mitochondrial stress response observed in pancreatic β-cells. These cells failed to mature and function properly, reinforcing the idea that mitochondrial dysfunction plays a widespread role in diabetes-related complications.

Although the researchers did not examine every tissue type affected by diabetes, their findings suggest that this mitochondrial pathway could contribute to dysfunction across multiple organ systems.

A Potential Path to Diabetes Treatment

One of the most striking aspects of the study was the discovery that mitochondrial damage did not result in cell death. Instead, the affected cells remained alive but in a dysfunctional, immature state. This raised the possibility that reversing mitochondrial damage could restore normal cell function.

To test this, the researchers treated the diabetic mice with ISRIB, a drug that blocks the stress response triggered by mitochondrial dysfunction. After four weeks of treatment, the β-cells regained their ability to regulate glucose levels, suggesting that the damage could be reversed.

“Losing your β-cells is the most direct path to getting type 2 diabetes. Through our study, we now have an explanation for what might be happening and how we can intervene and fix the root cause,” Soleimanpour said.

The Future of Diabetes Research

The findings offer a promising new approach for treating diabetes at its root cause rather than just managing symptoms. The research team is now working to further dissect the molecular pathways involved in mitochondrial stress responses. They hope to replicate their results using human cell samples from diabetic patients.

Mitochondrial dysfunction has long been recognized as a hallmark of metabolic diseases, but this study provides new evidence that it actively drives disease progression by altering cellular identity. By targeting the mitochondrial stress response, scientists may be able to restore proper cellular function and develop more effective treatments for diabetes.

The implications extend beyond diabetes, as mitochondrial dysfunction is also linked to other metabolic disorders. Understanding how mitochondria communicate with the nucleus to influence cell fate could open new avenues for treating a wide range of diseases.

With further research, these findings could revolutionize the way diabetes and other metabolic conditions are treated in the future.

Note: Materials provided above by The Brighter Side of News. Content may be edited for style and length.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News' newsletter.

Rebecca Shavit

Science & Technology Journalist | Innovation Storyteller

Based in Los Angeles, Rebecca Shavit is a dedicated science and technology journalist who writes for The Brighter Side of News, an online publication committed to highlighting positive and transformative stories from around the world. With a passion for uncovering groundbreaking discoveries and innovations, she brings to light the scientific advancements shaping a better future. Her reporting spans a wide range of topics, from cutting-edge medical breakthroughs and artificial intelligence to green technology and space exploration. With a keen ability to translate complex concepts into engaging and accessible stories, she makes science and innovation relatable to a broad audience.