James Webb telescope captures first images of CO2 outside solar system

JWST captures direct images of exoplanet atmospheres, revealing carbon dioxide and confirming formation theories in HR 8799 and 51 Eridani.

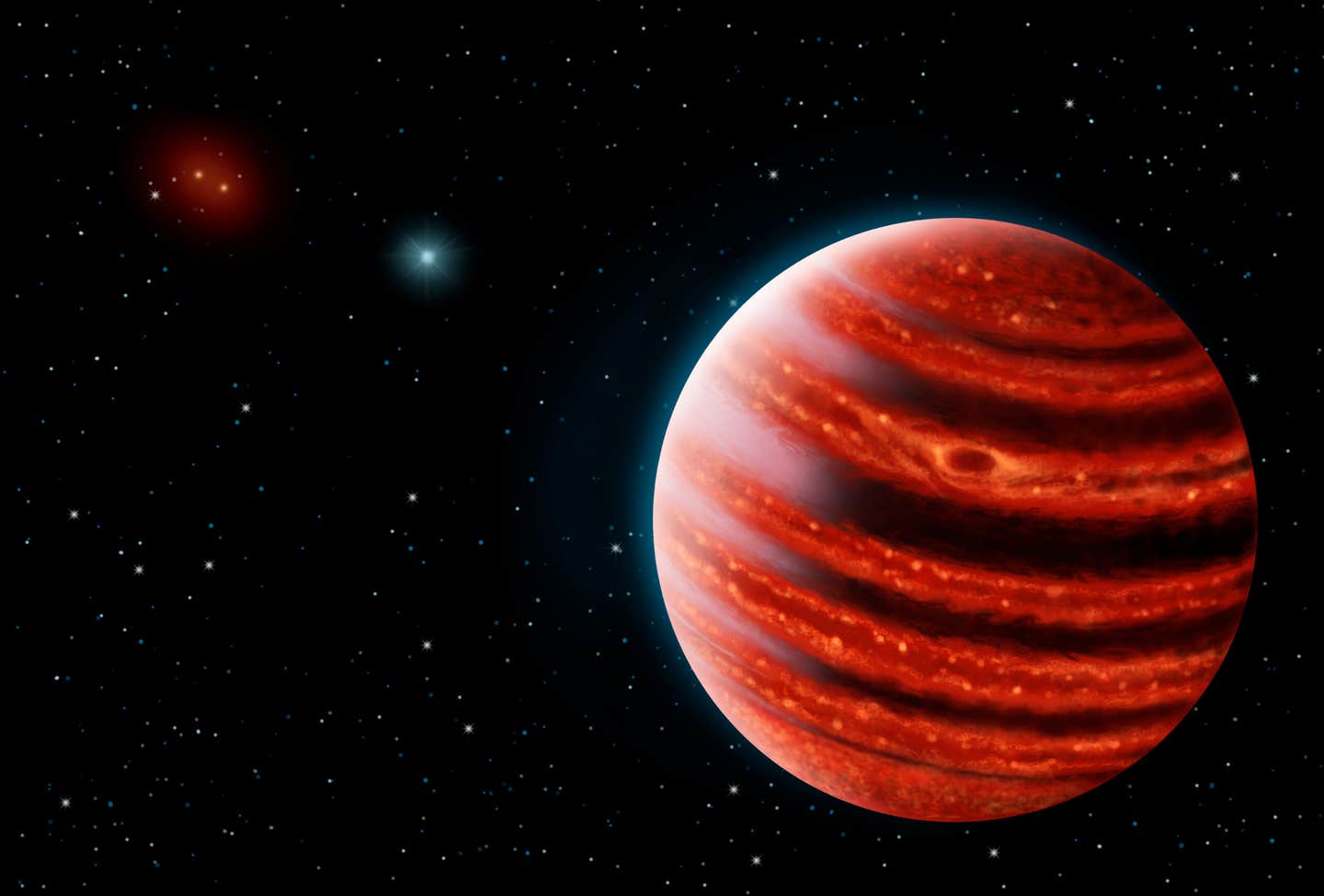

An artistic conception of the Jupiter-like exoplanet, 51 Eridani b, seen in the near-infrared light that shows the hot layers deep in its atmosphere glowing through clouds. Because of its young age, this young cousin of our own Jupiter is still hot and carries information on the way it was formed 20 million years ago. (CREDIT: CC BY-SA 4.0)

For years, astronomers have sought a way to directly observe the atmospheres of exoplanets, worlds orbiting distant stars. Unlike indirect detection methods, such as transit observations or radial velocity measurements, direct imaging allows scientists to analyze exoplanet atmospheres independently of their host stars.

However, the extreme contrast in brightness between stars and their planets makes this an immense challenge. With the powerful capabilities of the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), researchers are now overcoming these obstacles and gaining unprecedented insight into the formation and composition of exoplanets.

The Challenge of Direct Imaging

The brightness difference between a star and its orbiting exoplanet can be enormous, often exceeding a factor of a billion. This makes capturing a planet’s faint glow extremely difficult.

Traditional ground-based telescopes equipped with adaptive optics have detected some large gas giants, known as super-Jovian planets, located at wide orbits. These planets, typically 2 to 13 times the mass of Jupiter, have been identified at distances ranging from 10 to 1000 astronomical units (AU) from their stars.

Despite their rarity, directly imaged exoplanets are crucial for understanding planetary formation. By studying these objects, researchers can test theories about how gas giants like Jupiter and Saturn formed. The JWST, with its ability to detect infrared light, can observe much cooler and smaller planets than ever before.

Unlike its successors, such as the upcoming Roman Space Telescope, JWST lacks advanced coronagraphic technology designed to block out starlight. Instead, it relies on starlight subtraction algorithms, differential imaging techniques, and the telescope’s extreme stability to isolate planetary signals.

Related Stories

Cutting-Edge Coronagraphy and Imaging Techniques

JWST’s Near Infrared Camera (NIRCam) includes specialized coronagraphs designed to suppress starlight and enhance the visibility of orbiting planets. These coronagraphs come in two types: round masks and bar (or wedge) masks. Each has specific advantages—round masks offer a wider field of view, while bar masks allow for better detection of planets at close separations from their stars.

One of the telescope’s most significant early findings involved the multiplanet system HR 8799, located 130 light-years away. Using JWST’s coronagraphs, astronomers detected strong carbon dioxide features in the atmospheres of the system’s four giant planets.

These detections provide compelling evidence that these planets formed through core accretion, a process in which solid material gradually builds up to form a planetary core before attracting a surrounding atmosphere. This mechanism is believed to be responsible for the formation of Jupiter and Saturn in our solar system.

“We have shown there is a sizable fraction of heavier elements, such as carbon, oxygen, and iron, in these planets’ atmospheres,” said William Balmer, an astrophysicist at Johns Hopkins University leading the research. “Given what we know about the star they orbit, that likely indicates they formed via core accretion, which for planets that we can directly see is an exciting conclusion.”

Another breakthrough involved observations of 51 Eridani, a system 96 light-years away. JWST captured direct images of its planet, 51 Eridani b, at a wavelength of 4.1 micrometers, demonstrating its ability to detect exoplanets across a broad infrared spectrum.

These findings confirm that Webb can do more than infer atmospheric composition through starlight measurements—it can directly analyze exoplanet atmospheres.

Expanding the Boundaries of Planetary Science

Direct imaging of exoplanets is rare due to the extreme contrast between planets and their stars. However, JWST’s ability to capture light at wavelengths between 3 and 5 micrometers has allowed astronomers to detect atmospheric gases with precision.

The observations of HR 8799, for instance, revealed that the four giant planets contain more heavy elements than previously thought. This discovery supports theories that giant planets can act as stabilizers in planetary systems, influencing the formation and survival of smaller, potentially habitable planets.

Laurent Pueyo, an astronomer at the Space Telescope Science Institute, emphasized the significance of these results: “How common is this for long-period planets we can directly image? We don’t know yet, but we're proposing more Webb observations, inspired by our carbon dioxide diagnostics, to answer that question.”

By comparing these planets’ compositions to theoretical models, scientists hope to determine how frequently planets form through core accretion versus alternative mechanisms, such as gravitational collapse. These insights could help astronomers assess whether our solar system’s architecture is typical or an anomaly in the universe.

The Future of Exoplanet Characterization

The success of JWST’s coronagraphs paves the way for more ambitious studies of exoplanets. Future missions, including the Roman Space Telescope, will incorporate even more advanced coronagraphic technology to improve contrast and resolution.

Meanwhile, JWST continues to refine its capabilities, with astronomers exploring new observation techniques to push the boundaries of what can be detected.

Rémi Soummer, director of the Optics Laboratory at the Space Telescope Science Institute, noted that JWST’s precision has exceeded expectations. “We have been waiting for 10 years to confirm that our finely tuned operations of the telescope would also allow us to access the inner planets. Now the results are in, and we can do interesting science with it.”

By directly imaging exoplanets, scientists can better understand their atmospheric properties, formation history, and potential for habitability. These discoveries bring us closer to answering fundamental questions about the diversity of planetary systems and the conditions necessary for life beyond Earth.

Balmer highlighted the broader implications of these findings: “If you have these huge planets acting like bowling balls running through your solar system, they can either really disrupt, protect, or do a little bit of both to planets like ours.

Understanding more about their formation is a crucial step to understanding the formation, survival, and habitability of Earth-like planets in the future.”

Note: Materials provided above by The Brighter Side of News. Content may be edited for style and length.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News' newsletter.

Joshua Shavit

Science & Technology Writer | AI and Robotics Reporter

Joshua Shavit is a Los Angeles-based science and technology writer with a passion for exploring the breakthroughs shaping the future. As a contributor to The Brighter Side of News, he focuses on positive and transformative advancements in AI, technology, physics, engineering, robotics and space science. Joshua is currently working towards a Bachelor of Science in Business Administration at the University of California, Berkeley. He combines his academic background with a talent for storytelling, making complex scientific discoveries engaging and accessible. His work highlights the innovators behind the ideas, bringing readers closer to the people driving progress.