In a global first, scientists control electrons with twisted light

Scientists use structured light to control electron ionization, opening doors for breakthroughs in quantum computing and plasma physics.

Researchers have discovered that structured light beams can precisely control electron ejection from atoms. (CREDIT: CC BY-SA 4.0)

Scientists have long used Gaussian beams to study how light interacts with matter. These beams resemble plane waves and rely mostly on dipole-active transitions. Because atoms are much smaller than the wavelengths of visible light, higher-order interactions often get ignored.

But structured light beams, which can vary in frequency, amplitude, polarization, and phase, introduce new ways for light to interact with matter. These specially designed beams open up possibilities in quantum information, imaging, and laser technology.

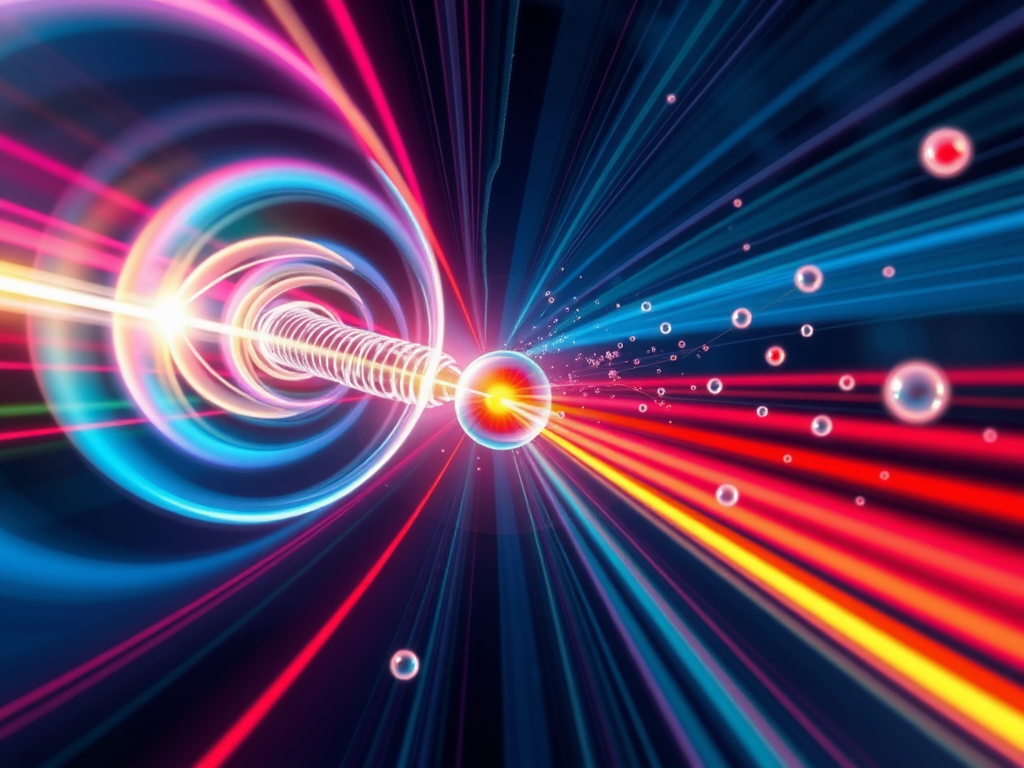

One fascinating type of structured light is the optical vortex beam. These beams carry orbital angular momentum (OAM), meaning each photon has a defined amount of rotational energy.

Unlike standard laser beams, optical vortex beams have a twisted wavefront, causing their central intensity to drop to zero. This property makes them useful in areas like particle trapping, quantum communication, and high-resolution imaging.

Challenging Traditional Ionization Theory

When light interacts with atoms, the dipole approximation usually holds—meaning only the simplest interactions are considered. But when structured light carries OAM, this approximation may not be valid. Factors like field gradients and magnetic dipole effects begin to play a role. Under extreme conditions, these effects can significantly impact ionization, the process where atoms lose electrons.

Researchers have used high-intensity lasers to create extreme ultraviolet light and terahertz pulses, but the role of OAM in photoionization remains unclear. Standard methods of controlling ionization include shaping laser pulses or using different wavelengths of light, but structured light introduces a new level of control.

A recent study from the University of Ottawa demonstrates that strong-field ionization can be influenced by structured light beams. The team, led by Professor Ravi Bhardwaj and PhD student Jean-Luc Begin, worked alongside Professors Ebrahim Karimi, Paul Corkum, and Thomas Brabec.

Related Stories

Their research shows that the handedness of an optical vortex beam—whether it twists left or right—affects ionization rates. By shifting the beam’s phase singularity, they achieved precise control over how electrons escape from atoms and molecules.

A Breakthrough in Electron Control

Ionization is a key process in physics, playing a role in plasma formation, X-ray generation, and even the northern lights. Traditionally, scientists believed they could only manipulate this process within certain limits. The Ottawa team’s research challenges this assumption.

“We have demonstrated that by using optical vortex beams—light beams that carry angular momentum—we can precisely control how an electron is ejected from an atom,” explains Professor Bhardwaj. “This discovery opens up new possibilities for enhancing technology in areas such as imaging and particle acceleration.”

The team used Laguerre-Gaussian (LG) beams in their experiments. These beams, unlike standard Gaussian beams, have an asymmetric intensity distribution and a twisted phase profile. The researchers found that by altering the position of the phase singularity, they could selectively ionize atoms and molecules. This effect, known as helical dichroism, had not been observed before.

Simulating the Ionization Process

To understand the underlying physics, the team extended the Strong-Field Approximation (SFA), a model used to describe electron behavior in intense laser fields. Their simulations incorporated multipole effects—additional forces that become important when structured light is involved.

They found that OAM changes how electrons tunnel out of an atom. The twisted nature of the LG beam distorts the atomic potential differently depending on the light’s handedness, leading to variations in ionization rates.

The researchers also discovered that the field gradient in asymmetric LG beams enhances both the peak ponderomotive energy (the average energy of an electron in an oscillating field) and the ponderomotive force. This means they could fine-tune the energy and location of ionization events at subwavelength scales. Such control could lead to advances in attosecond science, where researchers study electron movement on timescales shorter than a trillionth of a second.

Future Applications and Impact

This work is more than a theoretical breakthrough—it has practical implications. Structured light could be used in advanced imaging techniques that surpass current resolution limits. It may also improve quantum computing, where controlling individual particles is essential.

“This isn't just for physics textbooks,” Bhardwaj emphasizes. “It could lead to better medical imaging, faster computers, and more efficient ways to study materials.”

By showing that OAM can influence ionization, this study lays the groundwork for new experiments in atomic physics, spectroscopy, and plasma science. It also suggests that structured light might be used to control chemical reactions at a fundamental level.

The research, titled Orbital Angular Momentum Control of Strong-Field Ionization in Atoms and Molecules, was published in Nature Communications.

Over two years, the team at uOttawa’s Advanced Research Complex conducted experiments and refined their theoretical models. Their findings redefine how scientists think about light-matter interactions, offering a fresh perspective on ionization.

As structured light continues to evolve, its potential applications will expand across multiple scientific fields. From precision imaging to next-generation electronics, the ability to manipulate electrons with twisted light could shape the future of technology.

Note: Materials provided above by The Brighter Side of News. Content may be edited for style and length.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News' newsletter.

Joshua Shavit

Science & Technology Writer | AI and Robotics Reporter

Joshua Shavit is a Los Angeles-based science and technology writer with a passion for exploring the breakthroughs shaping the future. As a contributor to The Brighter Side of News, he focuses on positive and transformative advancements in AI, technology, physics, engineering, robotics and space science. Joshua is currently working towards a Bachelor of Science in Business Administration at the University of California, Berkeley. He combines his academic background with a talent for storytelling, making complex scientific discoveries engaging and accessible. His work highlights the innovators behind the ideas, bringing readers closer to the people driving progress.