Immune cells can prevent cognitive decline, study finds

Increasing evidence indicates close interaction between immune cells and the brain, revising the traditional view of the immune privilege.

[Dec. 1, 2022: Andrew Smith, Rutgers University]

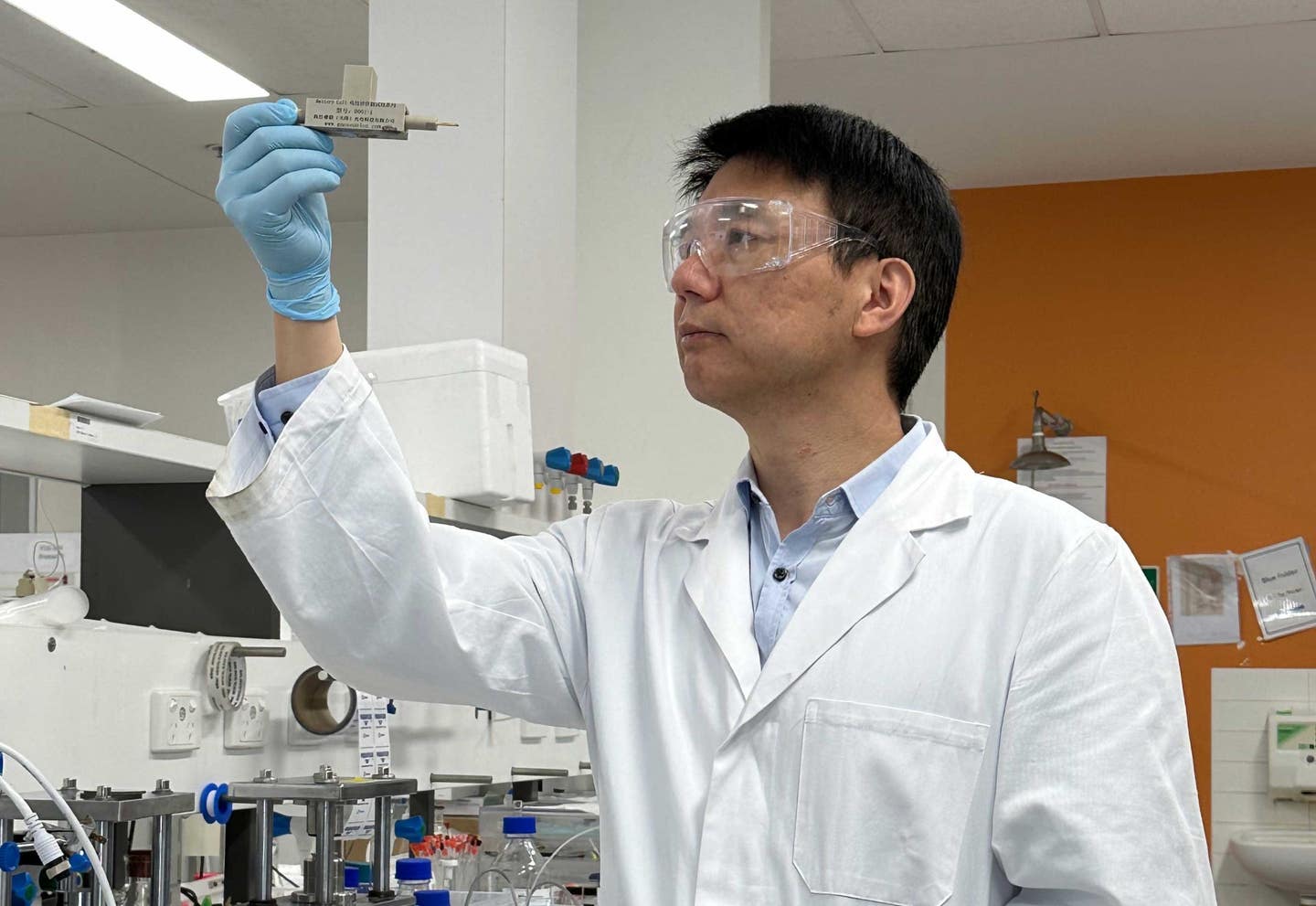

Increasing evidence indicates close interaction between immune cells and the brain, revising the traditional view of the immune privilege of the brain. (Credit: Creative Commons)

Increasing evidence indicates close interaction between immune cells and the brain, revising the traditional view of the immune privilege of the brain. However, the specific mechanisms by which immune cells promote normal neural function are not entirely understood.

Could the underproduction of poorly understood immune cells contribute to Alzheimer’s disease and other forms of cognitive decline? A Rutgers study in Nature Immunology suggests it may – and that increasing these cells could reverse the damage.

Mucosal-associated invariant T cells (MAIT cells) are a unique type of innate-like T cell with molecular and functional properties that remain to be better characterized. In the present study, we report that MAIT cells are present in the meninges and express high levels of antioxidant molecules.

MAIT cell deficiency in mice results in the accumulation of reactive oxidative species in the meninges, leading to reduced expression of junctional protein and meningeal barrier leakage. The presence of MAIT cells restricts neuroinflammation in the brain and preserves learning and memory.

Related Stories

Together, the researchers work reveals a new functional role for MAIT cells in the meninges and suggests that meningeal immune cells can help maintain normal neural function by preserving meningeal barrier homeostasis and integrity.

How did it work?

Rutgers researchers deactivated the gene that produces mucosal-associated invariant T cells (MAITs) in mice and compared the cognitive function of normal and MAIT cell-deficient mice. Initially, the two groups performed identically, but as the mice grew into middle age, the genetically altered mice struggled to form new memories.

Researchers then injected the genetically altered mice with MAITs, and their performance in learning and memory-intensive tasks, such as swimming through a water maze, returned to normal.

The study authors believe this is the first work to link MAITs to cognitive function and hope to follow it up with research that compares MAIT numbers in healthy humans and those with cognitive diseases such as Alzheimer’s.

“The MAIT cells that protect the brain are located in the meninges, but they are also present in blood, so a simple blood test should let us compare levels in healthy subjects and those with Alzheimer’s disease and other cognitive disorders,” said Qi Yang, senior author of the study and associate professor at the Child Health Institute of New Jersey at Rutgers Robert Wood Johnson Medical School.

MAIT cells, which were discovered in the 1990s, were already known to be the most abundant innate-like T cells in humans and to be particularly numerous in the liver and skin.

The Rutgers study was the first to detect these cells, which are not fully understood when it comes to fighting disease, in the meninges, the membrane layers that cover the brain.

MAIT cells help preserve meningeal barrier integrity. (CREDIT: Nature)

MAITs nested in the meninges appear to protect against cognitive decline by creating antioxidant molecules that combat toxic byproducts of energy production called reactive oxidative species.

Without MAITs, the reactive oxidative species accumulate in the meninges and cause meningeal barrier leakage. When the meningeal barrier leaks, potentially toxic substances enter and inflame the brain. This accumulation eventually disrupts brain and cognitive function.

MAIT cell activation in bacterial and viral infection. (CREDIT: Nature)

Genetic alteration prevented the experimental mice from producing any MAIT cells, but humans can probably increase MAIT cell production by altering their diets or making other lifestyle changes, said Yuanyue Zhang, the lead author of the study and a postdoctoral researcher at the Child Health Institute of New Jersey.

“MAIT cell production is connected to the bacteria in your gut microbiome,” Zhang said. “People who grew up in relatively sterile environments or took antibiotics frequently make fewer of them than people who grew up in more rural areas, where there is more exposure to beneficial bacteria. But everyone may improve their microbiota by changing their diet or living environment. This is just one more reason to pursue a natural and healthy lifestyle.”

Note: Materials provided above by Rutgers University. Content may be edited for style and length.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get the Brighter Side of News' newsletter.

Joseph Shavit

Head Science News Writer | Communicating Innovation & Discovery

Based in Los Angeles, Joseph Shavit is an accomplished science journalist, head science news writer and co-founder at The Brighter Side of News, where he translates cutting-edge discoveries into compelling stories for a broad audience. With a strong background spanning science, business, product management, media leadership, and entrepreneurship, Joseph brings a unique perspective to science communication. His expertise allows him to uncover the intersection of technological advancements and market potential, shedding light on how groundbreaking research evolves into transformative products and industries.