Global-first study reveals life’s resilience in extreme conditions

Microbes thrive deep underground, rivaling surface biodiversity. A groundbreaking study reveals life’s resilience in extreme conditions

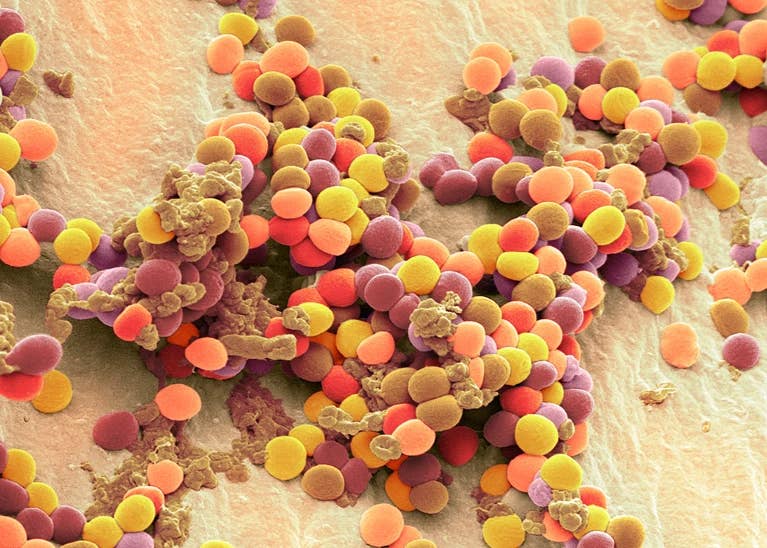

Scientists uncover thriving microbial communities deep underground, challenging assumptions about life’s limits. (CREDIT: CC BY-SA 4.0)

Microbial life thrives in some of the most extreme environments on Earth. Bacteria, archaea, and other microorganisms inhabit deep ocean trenches, acidic hot springs, and the frozen tundra.

While most microbial biomass exists in surface ecosystems, the majority of Earth's bacterial and archaeal carbon is stored beneath the surface. These subsurface environments range from just a few meters underground to kilometers beneath the Earth's crust and ocean floor.

Life in the Deep, Dark, Slow Lane

At continental margins, particularly near large river mouths, sediment thickness can reach 10 kilometers. In some places, the habitable crust extends over 15 kilometers deep. Despite the extreme conditions, microbial life persists.

Marine subsurface ecosystems host a significant abundance of archaea, often more than in surface environments. Subsurface microbes may account for more than half of all microbial cells on Earth, totaling around 5 to 12 x 10^29 cells.

Organic matter from the ocean surface gradually settles into deep sediment layers, bringing microbes along with it. Similarly, terrestrial subsurface microbes enter deeper layers through groundwater flow.

Even with drastic differences in light, oxygen levels, pressure, and nutrient availability, connections between surface and subsurface life exist. Microbes in these environments rely on survival mechanisms such as altered enzyme production, slow metabolism, and increased DNA repair activity.

In some of the most extreme subsurface environments, microbes metabolize energy sources like hydrogen, methane, and sulfur. Others survive through fermentation of microbial biomass or symbiotic relationships. Some even obtain energy through radiolysis, where radiation splits water molecules, creating hydrogen that microbes can use.

Related Stories

Many subsurface microbes remain in a dormant state, while others actively metabolize but have incredibly slow generation times—some dividing only once every 1,000 years.

A Groundbreaking Study

A comprehensive global study led by Emil Ruff at the Marine Biological Laboratory (MBL) in Woods Hole analyzed microbial diversity across deep terrestrial and marine subsurface environments. The study, published in Science Advances, revealed that microbial diversity deep underground can rival or even exceed that of surface ecosystems.

“It’s commonly assumed that the deeper you go, the less energy is available, and the fewer cells can survive,” Ruff explains. “But we show that in some subsurface environments, diversity can easily match surface diversity. This is especially true for marine environments and archaea.”

This groundbreaking study, taking eight years to complete, is one of the first to compare marine and terrestrial microbial diversity on such a large scale. The research analyzed over 1,400 globally distributed 16S rRNA gene datasets and taxonomic marker genes from 147 metagenomes.

The team sought to answer fundamental questions about how microbial communities differ between land and sea, surface and subsurface, and whether these deep environments harbor unique microbial lineages.

Comparing the Surface and Subsurface Microbiomes

The study found that microbial life on land and in the ocean is fundamentally different, with distinct communities shaped by environmental pressures. Marine and terrestrial microbiomes differ greatly in composition, but their overall diversity levels are comparable. This pattern extends into subsurface environments as well.

“Look at plants and animals—very few species can adapt to both land and sea. The same seems to be true for microbes,” Ruff says. “There’s a clear divide between life forms in marine and terrestrial realms, even in the deep biosphere. The selective pressures in each environment shape vastly different microbial communities.”

While subsurface ecosystems contain significant biomass, their biodiversity compared to surface ecosystems remains uncertain. Earlier studies suggested distinct microbiomes between land and sea, but previous research often lacked a standardized approach.

This study overcame those limitations by analyzing data using consistent sequencing methods. The Census of Deep Life, co-led by MBL scientist Mitchell Sogin, provided a standardized dataset, allowing direct comparisons across more than 1,000 samples from 50 different ecosystems.

“For the first time, we could directly compare microbiomes from, say, Great Lakes surface sediment with sediment from two kilometers below the seafloor,” Ruff explains. “That’s what makes this study unique.”

Implications for Earth and Beyond

The findings have broad implications, from bioprospecting for new compounds to understanding how life can persist in extreme environments. Many microbes found in these deep ecosystems have never been cultured in a lab, presenting new opportunities for discovering novel enzymes and bioactive molecules.

These discoveries also provide clues in the search for extraterrestrial life. If Mars once had liquid water, its deep rock environments might resemble those on Earth. Subsurface microbes on Earth survive in low-energy environments with slow generation times. If life existed on Mars, similar microbes could still persist deep underground today.

Understanding how microbes adapt to low-energy conditions also has potential applications in medicine and aging research. Some deep-sea microbes show remarkably slow biological processes, which could provide insight into cellular longevity and energy efficiency.

“If Mars or other planets had liquid water at some point, their rocky subsurface ecosystems would look very similar to ours,” Ruff says. “The organisms’ generation times would be very long, and their energy requirements minimal. Studying deep life on Earth gives us a model for what to look for elsewhere in the universe.”

This study marks a major step forward in microbial ecology, revealing an unseen world teeming with life beneath our feet. The more we explore these hidden biospheres, the more we understand the resilience of life—and its potential beyond Earth.

Note: Materials provided above by The Brighter Side of News. Content may be edited for style and length.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News' newsletter.

Joseph Shavit

Head Science News Writer | Communicating Innovation & Discovery

Based in Los Angeles, Joseph Shavit is an accomplished science journalist, head science news writer and co-founder at The Brighter Side of News, where he translates cutting-edge discoveries into compelling stories for a broad audience. With a strong background spanning science, business, product management, media leadership, and entrepreneurship, Joseph brings a unique perspective to science communication. His expertise allows him to uncover the intersection of technological advancements and market potential, shedding light on how groundbreaking research evolves into transformative products and industries.