Earth’s global temperature has drastically changed over the last 500 million years

Earth’s climate over the last 485 million years fluctuated far more than previously thought, with CO2 playing a dominant role. This study highlights how understanding ancient climates informs modern climate predictions.

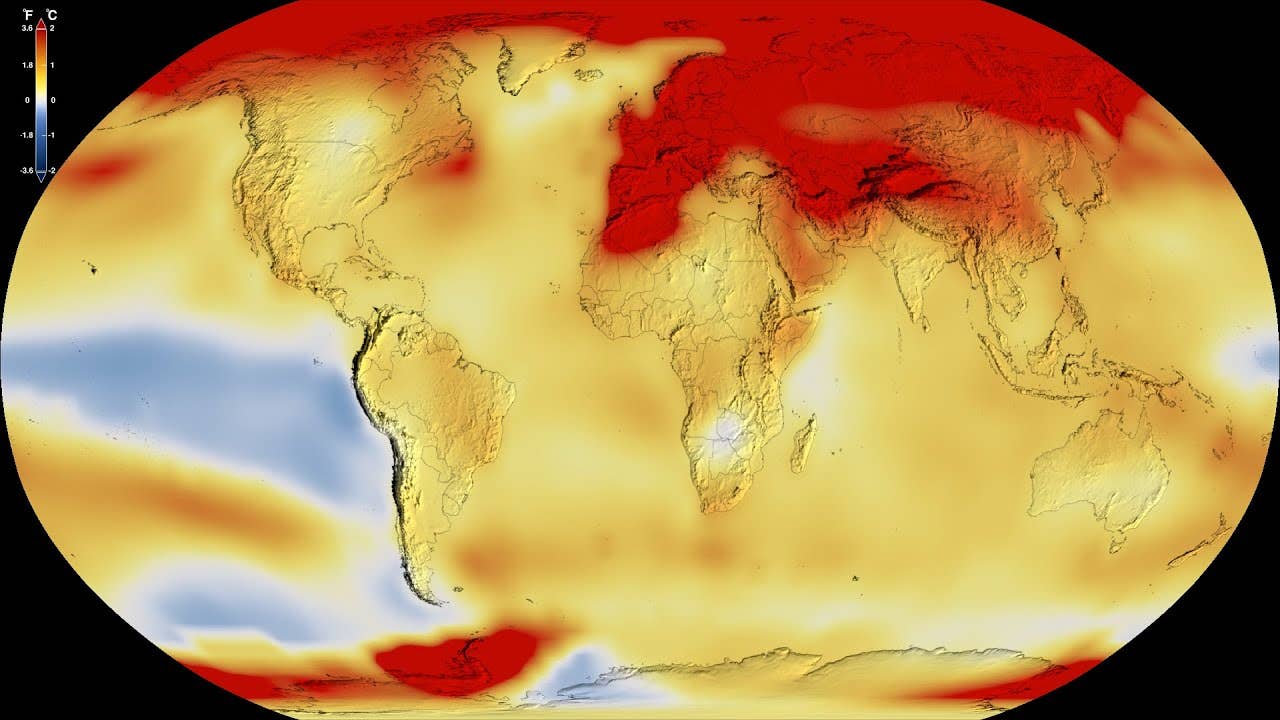

Global Warming from 1880 to 2022. (CREDIT: CC BY-SA 3.0)

A recent study published in Science unveils a detailed curve of global mean surface temperatures that highlights Earth's temperature fluctuations over the Phanerozoic Eon, a period when life diversified and survived multiple mass extinctions. The research offers a clearer picture of how global temperatures have changed over time, emphasizing the strong relationship between Earth's temperature and atmospheric carbon dioxide levels.

The Phanerozoic Eon began around 540 million years ago, marked by the Cambrian Explosion—a time when complex, hard-shelled organisms first appeared. While simulations can cover the entire Phanerozoic, this study focuses on the last 485 million years due to limited geological data available for earlier periods.

“It’s hard to find rocks that are that old and have temperature indicators preserved in them—even at 485 million years ago, we don’t have that many,” said Jessica Tierney, co-author and paleoclimatologist at the University of Arizona. The challenge of retrieving such ancient data restricts how far back researchers can analyze Earth’s climate.

The research team used a technique called data assimilation to generate the temperature curve. This method allowed them to merge geologic data with climate models, creating a more comprehensive understanding of ancient climates. Originally developed for weather forecasting, this approach was repurposed for climate research.

Related Stories

Emily Judd, lead author of the paper and former postdoctoral researcher at the Smithsonian and the University of Arizona, explained, “Instead of using it to forecast future weather, here we’re using it to hindcast ancient climates.”

A refined understanding of Earth’s historical temperature patterns is crucial for understanding contemporary climate change. Co-author Scott Wing, curator of paleobotany at the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History, pointed out that modern climate projections can't be compared to more recent periods of history.

“If you’re studying the last couple of million years, you won’t find anything that looks like what we expect in 2100 or 2500,” he said. “You need to go back even further to periods when the Earth was really warm. That’s the only way we’re going to get a better understanding of how the climate might change in the future.”

The findings reveal that global temperatures fluctuated far more than previously thought over the past 485 million years, with temperatures ranging from 52 to 97 degrees Fahrenheit. The warmest periods corresponded to high levels of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere.

Tierney highlighted the dominant role of CO2 in regulating global temperatures, stating, “This research illustrates clearly that carbon dioxide is the dominant control on global temperatures across geological time. When CO2 is low, the temperature is cold; when CO2 is high, the temperature is warm.”

Presently, the Earth's average global temperature is about 59 degrees Fahrenheit, cooler than much of the Phanerozoic era. However, human-induced climate change is driving temperature increases at an alarming rate.

This current rate of warming is faster than the most rapid warming events in the Phanerozoic and is placing ecosystems and species worldwide at risk. The study warns that accelerated warming could lead to significant disruptions in sea levels and biodiversity, akin to past episodes of rapid climate change that triggered mass extinctions.

Historically, humans have thrived within a relatively narrow global temperature range of about 10 degrees Fahrenheit. The vast majority of human civilization has evolved within what scientists call an “ice house” climate, where global temperatures have remained relatively low.

Tierney emphasized the precariousness of the situation, saying, “Our entire species evolved to an 'ice house' climate, which doesn’t reflect most of geological history. We are changing the climate into a place that is really out of context for humans. The planet has been and can be warmer, but humans and animals can’t adapt that fast.”

This research project began in 2018 as a collaboration between Tierney and researchers from the Smithsonian, with the goal of creating a temperature curve for museum visitors that would display Earth's temperature changes across the Phanerozoic Eon. The team gathered over 150,000 estimates of ancient temperatures derived from chemical indicators preserved in fossilized shells and other organic matter.

Complementing this data, their colleagues at the University of Bristol ran more than 850 climate model simulations to reconstruct Earth’s climate during different periods of the distant past. The researchers integrated these two data streams to produce the most detailed curve of Earth's temperature variations over the past 485 million years.

Another significant finding from the study relates to climate sensitivity, which measures how much the climate warms for each doubling of carbon dioxide. Tierney explained, “We found that carbon dioxide and temperature are not only really closely related, but related in the same way across 485 million years. We don’t see that the climate is more sensitive when it’s hot or cold.” This insight further underscores the consistency of CO2's influence on global temperatures over Earth's long history.

Along with Tierney, the study's co-authors include Emily Judd, Matthew Huber from Purdue University, Scott Wing from the Smithsonian, and Daniel Lunt and Paul Valdes from the University of Bristol. Isabel Montañez from the University of California, Davis, also contributed to the research.

Financial support for the study came from the Smithsonian's Roland and Debra Sauermann, the Heising-Simons Foundation, and the University of Arizona’s Thomas R. Brown Distinguished Chair in Integrative Science, as well as the UK's Natural Environment Research Council.

This groundbreaking research offers an invaluable long-term perspective on climate change, illuminating the powerful role of carbon dioxide in shaping Earth’s climate. As modern society confronts the accelerating impacts of global warming, this study provides critical context for what the future may hold—and a stark reminder of the planet’s climate history.

Note: Materials provided above by The Brighter Side of News. Content may be edited for style and length.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News' newsletter.