DNA study reveals modern humans evolved from two ancient groups

Genetic research uncovers two ancestral groups merging 300,000 years ago, reshaping our understanding of human evolution.

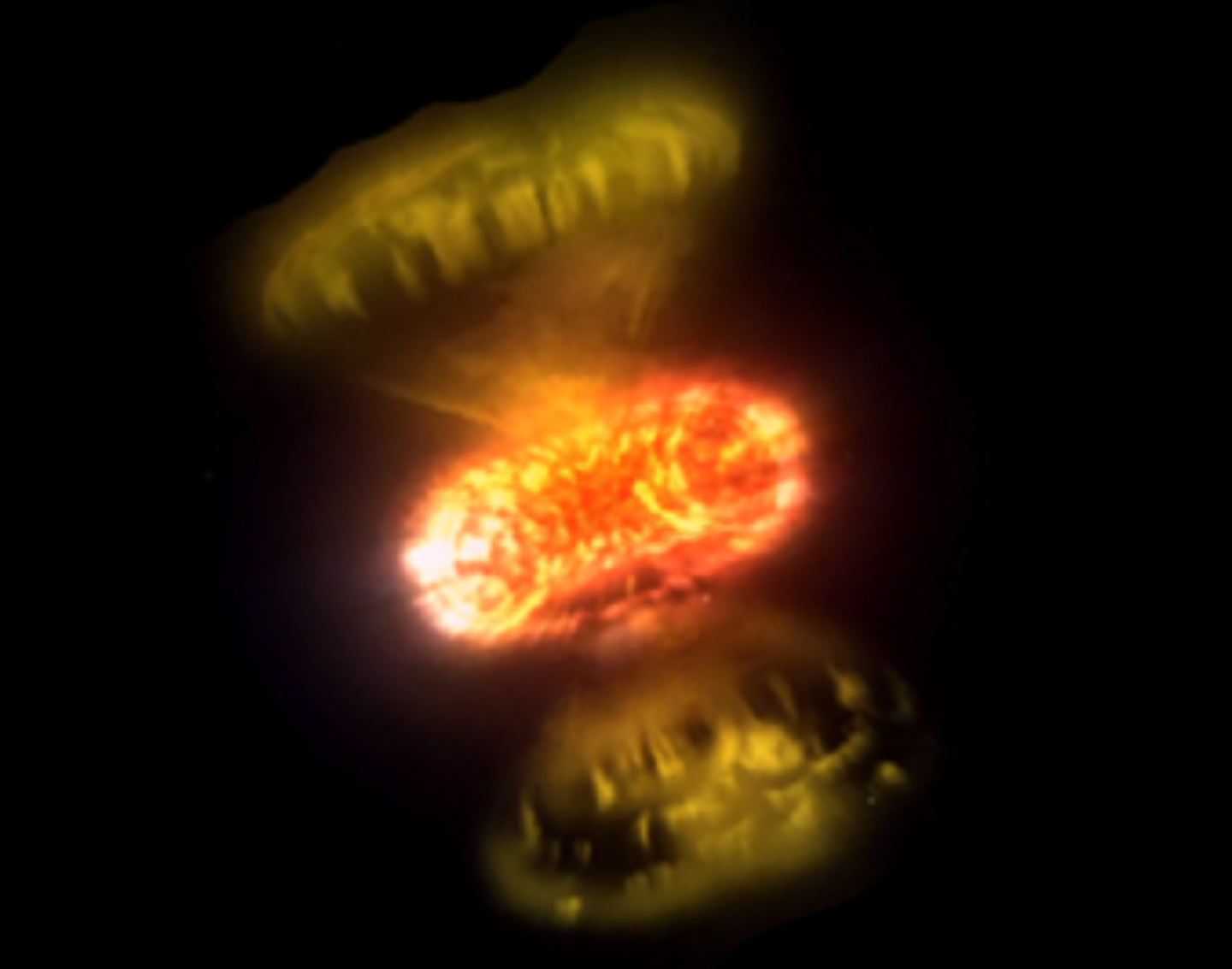

Modern humans evolved from two separate groups that split 1.5 million years ago and reunited later. (CREDIT: Martin Meissner)

Scientists have long debated how modern humans evolved. For decades, most researchers agreed that Homo sapiens came from one ancestral group in Africa, dating back 200,000 to 300,000 years.

But new genetic studies show that our origins involve two separate populations that first split apart around 1.5 million years ago and then reunited about 300,000 years ago. This reunion wasn't an equal mix; one group contributed about 80% of modern human DNA, and the other, only 20%.

Genetic Clues from Modern Humans

Traditionally, scientists relied on ancient bones to track human evolution. New methods using DNA from living humans, however, have opened a clearer window into our past. Researchers at the University of Cambridge studied genetic information collected from diverse groups worldwide, thanks to global projects that mapped the human genome.

To analyze this data, the Cambridge team created a new computational model called cobraa. Unlike older methods that assume populations were always mixed, cobraa looks specifically for evidence of populations splitting and then merging again. The team first tested cobraa with computer-generated scenarios and later applied it to real DNA data from humans and several animal species.

Discovering a Forgotten Split

The cobraa model revealed something surprising: modern human DNA doesn't match a simple evolutionary tree. Instead, researchers found clear genetic traces indicating a significant division lasting over a million years, followed by a critical reunion. The split began around 1.5 million years ago when two groups went separate ways. Roughly 1.2 million years later, around 300,000 years ago, these populations came back together, mixing their genes.

"For a long time, it's been assumed that we evolved from a single continuous ancestral lineage, but the exact details of our origins are uncertain," explained Dr. Trevor Cousins, the study’s lead author. This research provides strong evidence that our ancestors were more diverse and interconnected than previously thought.

Related Stories

Majority and Minority Contributors

Researchers identified two ancestral groups involved in the mixing event, but their contributions weren't equal. The larger population, which supplied around 80% of our modern genes, experienced a major population collapse shortly after it first separated.

"Immediately after the two ancestral populations split, we see a severe bottleneck in one of them—suggesting it shrank to a very small size before slowly growing over a period of one million years," said Professor Aylwyn Scally, a co-author on the study.

This larger group didn't just give rise to modern humans. Genetic evidence strongly suggests it was also ancestral to Neanderthals and Denisovans, two closely related species that interbred with our direct ancestors around 50,000 years ago. Neanderthal and Denisovan DNA, however, only accounts for about 2% of the genome in humans outside Africa. By comparison, the ancient mixing event uncovered by the Cambridge team contributed up to ten times as much DNA and is present in all humans today.

Genetic Challenges for the Smaller Group

The smaller ancestral population provided around 20% of our DNA, but these genetic contributions faced challenges. The team found that genes from the minority group often sit away from areas responsible for important functions like growth or metabolism.

This pattern suggests that genes from the smaller population were likely harmful when combined with those from the larger group, leading to their gradual removal by natural selection.

However, despite their smaller genetic footprint, this minority group might have had a significant influence on modern humans. Dr. Cousins highlights their potential impact, noting, "Some of the genes from the population which contributed a minority of our genetic material, particularly those related to brain function and neural processing, may have played a crucial role in human evolution."

Beyond Human Evolution

The cobraa algorithm isn't limited to human history. The researchers also applied it to other mammals, including chimpanzees, gorillas, dolphins, and bats. They found similar patterns of splitting and merging in some, but not all, of these animals. These findings suggest that mixing between separated populations may be common across many species, challenging the traditional view that species evolve along neat, distinct branches.

"What's becoming clear is that the idea of species evolving in clean, distinct lineages is too simplistic," Cousins remarked. "Interbreeding and genetic exchange have likely played a major role in the emergence of new species repeatedly across the animal kingdom."

Identifying the Ancestral Populations

While genetic evidence clearly points to these ancient populations, researchers haven't matched them definitively with fossil groups yet. Species such as Homo erectus and Homo heidelbergensis, who lived around this same period, are strong candidates. Yet more fossil evidence is needed to confirm these connections conclusively.

Scientists also plan to refine their cobraa model in the future, hoping to account for more gradual interactions between groups instead of sharp splits and reunions. This improved approach could provide even clearer insights into our evolutionary past.

Changing the Story of Our Past

This new genetic evidence significantly rewrites the story of human evolution. Instead of descending neatly from a single line, modern humans emerged from the blending of two long-separated groups. This finding reshapes not just how we understand ourselves, but how we view evolution as a whole.

Professor Richard Durbin, another co-author, emphasized the broader impact of this discovery, stating, "Our research shows clear signs that our evolutionary origins are more complex, involving different groups that developed separately for more than a million years, then came back to form the modern human species."

Professor Scally also reflected on the incredible power of modern genetics to illuminate ancient events. "The fact that we can reconstruct events from hundreds of thousands or millions of years ago just by looking at DNA today is astonishing," he said. "And it tells us that our history is far richer and more complex than we imagined."

Note: The article above provided above by The Brighter Side of News.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News' newsletter.