Berkelocene: Scientists create the world’s first organometallic molecule

Scientists have discovered berkelocene, the first organometallic molecule with berkelium, advancing actinide chemistry and nuclear science.

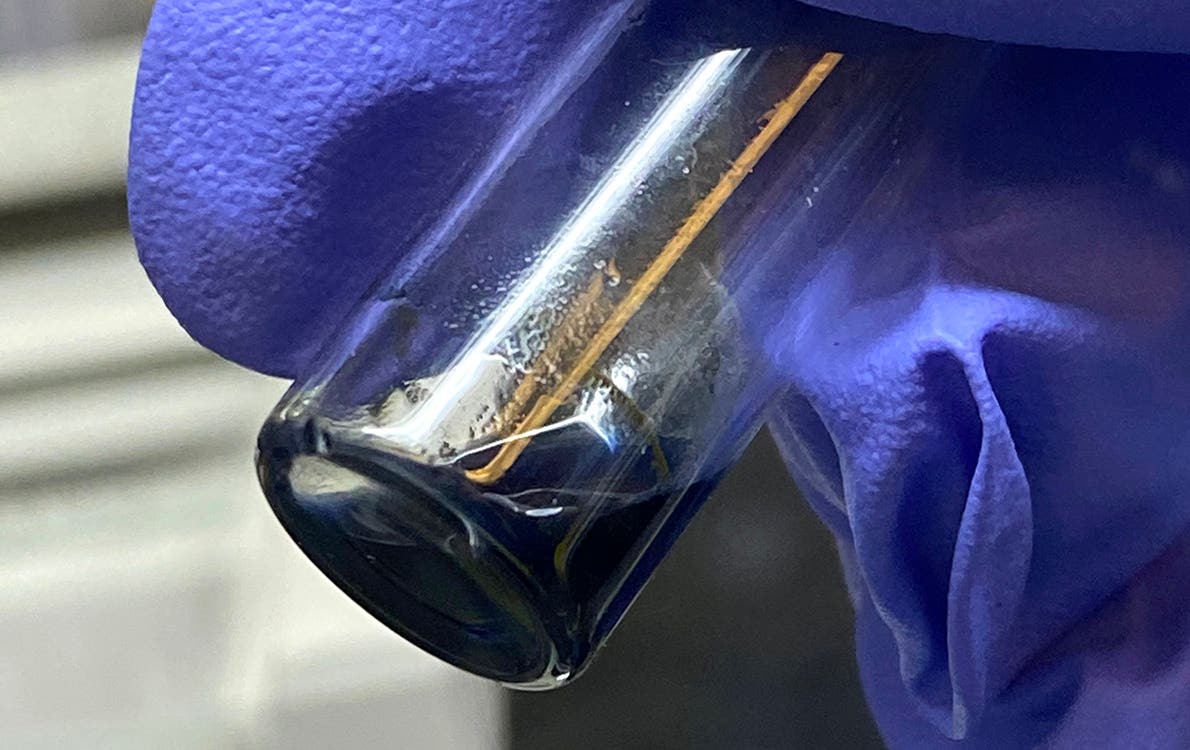

Researchers have synthesized and characterized berkelocene, a new organometallic molecule featuring the rare and highly radioactive element berkelium. (CREDIT: Alyssa Gaiser / Berkeley Lab)

Scientists at the Department of Energy’s Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Berkeley Lab) have made a groundbreaking discovery in the field of organometallic chemistry. They have synthesized and characterized berkelocene, a new organometallic molecule featuring the rare and highly radioactive element berkelium.

This marks the first time that berkelium has been successfully incorporated into a stable organometallic structure, offering fresh insights into actinide chemistry.

Organometallic compounds—molecules where metal atoms are bonded to carbon—are common in early actinide elements like uranium and thorium. However, they have remained elusive for later actinides such as berkelium. The discovery of berkelocene provides critical knowledge about how these heavy elements interact with other atoms, a key factor in nuclear waste management and material science.

“This is the first time that evidence for the formation of a chemical bond between berkelium and carbon has been obtained,” said Stefan Minasian, a scientist in Berkeley Lab’s Chemical Sciences Division. “The discovery provides new understanding of how berkelium and other actinides behave relative to their peers in the periodic table.”

Berkelium, discovered in 1949 by nuclear chemist Glenn Seaborg and his team at Berkeley Lab, is one of the 15 actinide elements in the periodic table’s f-block. It is highly radioactive and exists only in small amounts, making it challenging to study. Despite its discovery over 70 years ago, its chemistry remains largely unexplored due to these limitations.

Breaking the Barriers of Actinide Chemistry

For years, organometallic chemistry and actinide research progressed along separate paths. The 1950s saw the rise of modern organometallic chemistry with the discovery of ferrocene, a stable compound featuring iron sandwiched between two carbon rings. Around the same time, researchers isolated two new actinides—berkelium and californium. But early attempts to form organometallic compounds with actinides yielded highly reactive, air-sensitive molecules that decomposed quickly.

A breakthrough came in the late 1960s with the synthesis of uranocene, a uranium-based molecule with two eight-membered carbon rings. This structure was remarkably stable compared to earlier actinide compounds, sparking renewed interest in the field. By 1976, researchers had characterized actinocenes featuring thorium, uranium, neptunium, and plutonium, but the chemistry of heavier actinides remained largely unexplored.

Related Stories

Recent studies revisited the idea of bonding transplutonium elements, like americium and californium, with carbon. These studies hinted at largely ionic interactions, but researchers had yet to establish a clear picture of covalent bonding in these elements. The discovery of berkelocene now bridges that gap, demonstrating a stable carbon-actinide bond beyond plutonium for the first time.

A Precise and Delicate Process

Studying berkelium presents major challenges. It is highly radioactive, and only tiny amounts of it are produced globally each year. Additionally, organometallic compounds tend to be extremely sensitive to air and moisture, which makes them difficult to handle. To overcome these obstacles, the Berkeley Lab team designed custom gloveboxes that allowed air-free synthesis of highly radioactive isotopes.

With just 0.3 milligrams of berkelium-249—obtained from the National Isotope Development Center at Oak Ridge National Laboratory—the researchers conducted single-crystal X-ray diffraction experiments to determine its molecular structure. The results revealed a highly symmetrical molecule, where a berkelium atom was sandwiched between two eight-membered carbon rings.

“The structure is analogous to uranocene, which was discovered at UC Berkeley in the late 1960s,” said Minasian. The researchers named the new molecule berkelocene in recognition of this similarity.

One of the most surprising findings came from electronic structure calculations performed by Jochen Autschbach at the University of Buffalo. These calculations showed that berkelium in berkelocene adopts a tetravalent oxidation state (+4), something that was unexpected based on traditional periodic table trends.

“Traditional understanding of the periodic table suggests that berkelium would behave like the lanthanide terbium,” Minasian said. “But the berkelium ion is much happier in the +4 oxidation state than the other f-block ions we expected it to be most like.”

This unexpected stability challenges conventional theories about how actinides bond with other elements. It suggests that existing models need refinement to accurately describe the behavior of heavy elements.

Implications for Nuclear Science and Beyond

Understanding how actinides bond with other elements has broad implications, particularly in nuclear waste storage and remediation. Many of the challenges in handling nuclear waste stem from the unpredictable behavior of heavy elements like berkelium. More precise models of their chemistry could lead to better strategies for waste containment and recycling.

“More accurate models of actinide behavior are essential for solving problems related to nuclear waste and long-term storage,” said Rebecca Abergel, a UC Berkeley associate professor of nuclear engineering and chemistry.

Beyond nuclear science, berkelocene represents a significant step forward in fundamental chemistry. High-symmetry organometallic compounds like this one provide a window into the electronic structures of heavy elements, offering insights that could apply to other areas of chemistry and materials science.

“When scientists study higher symmetry structures, it helps them understand the underlying logic that nature is using to organize matter at the atomic level,” said Polly Arnold, director of Berkeley Lab’s Chemical Sciences Division.

The discovery of berkelocene is just the beginning. Researchers are now exploring whether similar organometallic molecules can be synthesized with other transplutonium elements. If so, this could open new doors in actinide chemistry, providing a clearer understanding of how these rare elements fit into the broader picture of the periodic table.

“This clearer portrait of later actinides like berkelium provides a new lens into the behavior of these fascinating elements,” Abergel said.

With each new discovery, scientists inch closer to unlocking the full potential of the periodic table’s heaviest and least understood elements.

Note: Materials provided above by The Brighter Side of News. Content may be edited for style and length.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News' newsletter.

Joshua Shavit

Science & Technology Writer | AI and Robotics Reporter

Joshua Shavit is a Los Angeles-based science and technology writer with a passion for exploring the breakthroughs shaping the future. As a contributor to The Brighter Side of News, he focuses on positive and transformative advancements in AI, technology, physics, engineering, robotics and space science. Joshua is currently working towards a Bachelor of Science in Business Administration at the University of California, Berkeley. He combines his academic background with a talent for storytelling, making complex scientific discoveries engaging and accessible. His work highlights the innovators behind the ideas, bringing readers closer to the people driving progress.