Bacteria and fungi in the brain linked to dementia and Alzheimer cure

Explore the emerging link between microbial infections and Alzheimer’s, offering new hope for diagnosing and treating dementia.

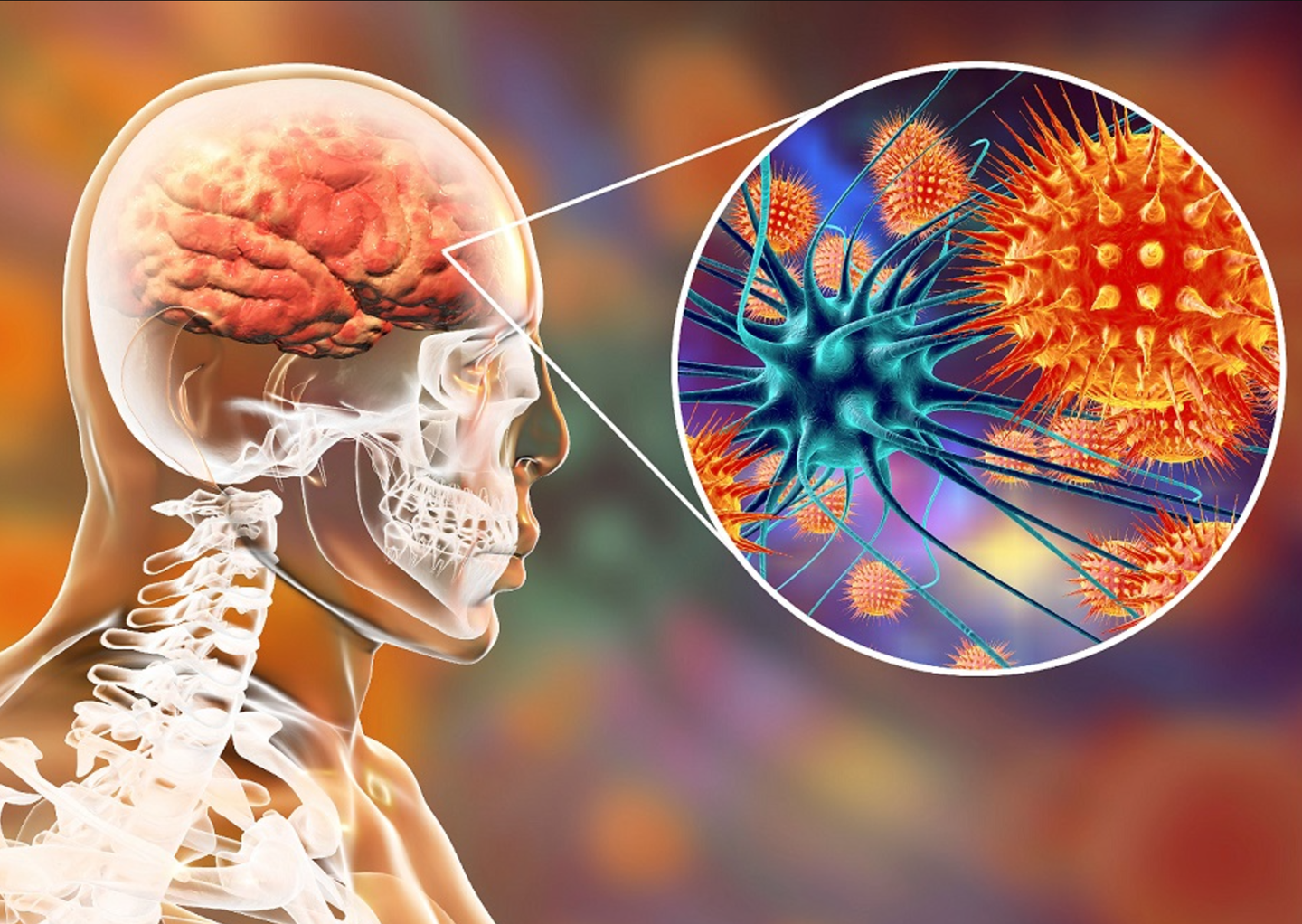

Research links microbial infections to Alzheimer’s. (CREDIT: Shutterstock)

Alzheimer’s disease (AD), a devastating brain disorder affecting millions globally, has long been a puzzle for researchers. Known for its slow progression and profound memory loss, AD has resisted decades of study, leaving no cure in sight.

Despite an investment of over $100 billion, its causes remain elusive. However, emerging evidence suggests that microbial infections might play a significant role in dementia, including AD. This notion, though controversial, has gained traction thanks to recent research and compelling patient stories.

Nine years ago, Nikki Schultek, a vibrant mother of two, faced a nightmare. Debilitating cognitive and physical symptoms left her undiagnosed after numerous scans and tests. Eventually, doctors discovered the culprit: Borrelia burgdorferi, the bacteria behind Lyme disease, had invaded her brain.

Antibiotics restored her health, but the journey underscored a critical gap in diagnosing and treating brain infections. Schultek’s story is not unique. A recent paper she co-authored highlights cases where infections, ranging from bacteria to fungi, were misdiagnosed as dementia. Remarkably, treatment often reversed cognitive decline.

The Overlooked Role of Infections in Dementia

Microbial infections have long been linked to various types of dementia. Infections such as Cryptococcus neoformans, a fungal pathogen, and Borrelia, have been implicated in numerous cases.

Other microbes, including herpes simplex and zoster viruses, have also been found in the brains of dementia patients. Yet, diagnosing these infections early remains challenging due to the lack of standardized methods.

The skepticism surrounding the infection-dementia connection dates back to Alois Alzheimer, who first described the disease over a century ago.

Both Alzheimer and his contemporary, Oskar Fischer, speculated about microbial involvement. However, technological limitations stifled further exploration. Today, advanced research methods have reignited interest in this theory.

Related Stories

Recent studies have revealed that the human brain, once thought sterile, hosts a diverse microbiome. In healthy brains, microbial communities are balanced, resembling the gut microbiome.

In Alzheimer’s patients, however, this balance often skews toward harmful overgrowths. Bacteria such as Streptococcus and Staphylococcus and fungi like Candida and Cryptococcus are frequently found in these cases.

Pioneering Research into the Brain Microbiome

Schultek now leads the Alzheimer’s Pathobiome Initiative, bringing together scientists across disciplines to explore how infections contribute to dementia. According to Richard Lathe, an infectious medicine expert at the University of Edinburgh, their findings suggest that up to 50% of dementia cases might be treatable if infections are addressed early.

The brain microbiome remains largely uncharted due to sampling challenges. Unlike the gut, the brain is protected by the blood-brain barrier, making it difficult to access microbial evidence.

Researchers like David Corry at Baylor College of Medicine have started culturing brain samples to identify microbes, while others use gene amplification techniques to confirm findings. These studies have uncovered previously unknown organisms, shedding light on the brain’s microbial complexity.

Vaccines could play a vital role in reducing dementia risk. The BCG vaccine, originally developed for tuberculosis, has shown promise in protecting against Alzheimer’s. Studies suggest it reduces risk by up to 75%. Vaccines for shingles, influenza, and other diseases also appear to offer some protection, likely by boosting overall immunity.

This connection between infections and cognitive decline extends beyond the brain. In Denmark, research has linked multiple infections to increased Alzheimer’s risk, while individuals with Alzheimer’s are more prone to infections. Maintaining a robust immune system may be key to mitigating these risks.

Preventing Brain Infections: A Multifaceted Approach

Timely treatment of infections throughout the body could help protect the brain. However, diagnosing brain infections often requires invasive procedures like lumbar punctures, which carry risks. Until non-invasive diagnostic tools are developed, raising awareness of infection-related dementia is crucial.

Lifestyle changes also play a role. Good oral hygiene, for instance, can reduce the risk of gum disease, which has been linked to increased blood-brain barrier permeability. A balanced diet and regular exercise support immune function, helping the body combat infections naturally.

Despite mounting evidence, skepticism persists. Some researchers dismiss the idea of microbes contributing to dementia, calling it improbable. Funding for such research remains limited, hindering progress. However, Schultek and her team remain undeterred, advocating for further studies to uncover the truth.

The potential implications are enormous. Understanding the brain microbiome and its role in dementia could transform treatment strategies. Vaccination campaigns, targeted antimicrobial therapies, and preventive measures might one day reduce the burden of Alzheimer’s disease worldwide.

Schultek’s journey from patient to advocate highlights the urgent need for change. Whether through better diagnostics, innovative treatments, or public awareness, addressing infections in dementia offers hope to millions. As Lathe notes, “Boosting the immune system and treating infections early could significantly alter the course of this disease.”

Note: Materials provided above by The Brighter Side of News. Content may be edited for style and length.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News' newsletter.

Joseph Shavit

Head Science News Writer | Communicating Innovation & Discovery

Based in Los Angeles, Joseph Shavit is an accomplished science journalist, head science news writer and co-founder at The Brighter Side of News, where he translates cutting-edge discoveries into compelling stories for a broad audience. With a strong background spanning science, business, product management, media leadership, and entrepreneurship, Joseph brings a unique perspective to science communication. His expertise allows him to uncover the intersection of technological advancements and market potential, shedding light on how groundbreaking research evolves into transformative products and industries.