Artificial greenhouse gases could signal alien activity on terraformed planets

If aliens altered a planet to make it warmer, we’d be able to detect it, a new study from UC Riverside concludes.

If aliens altered a planet to make it warmer, we’d be able to detect it. A new study from the University of California, Riverside, reveals specific artificial greenhouse gases that could signal a terraformed planet.

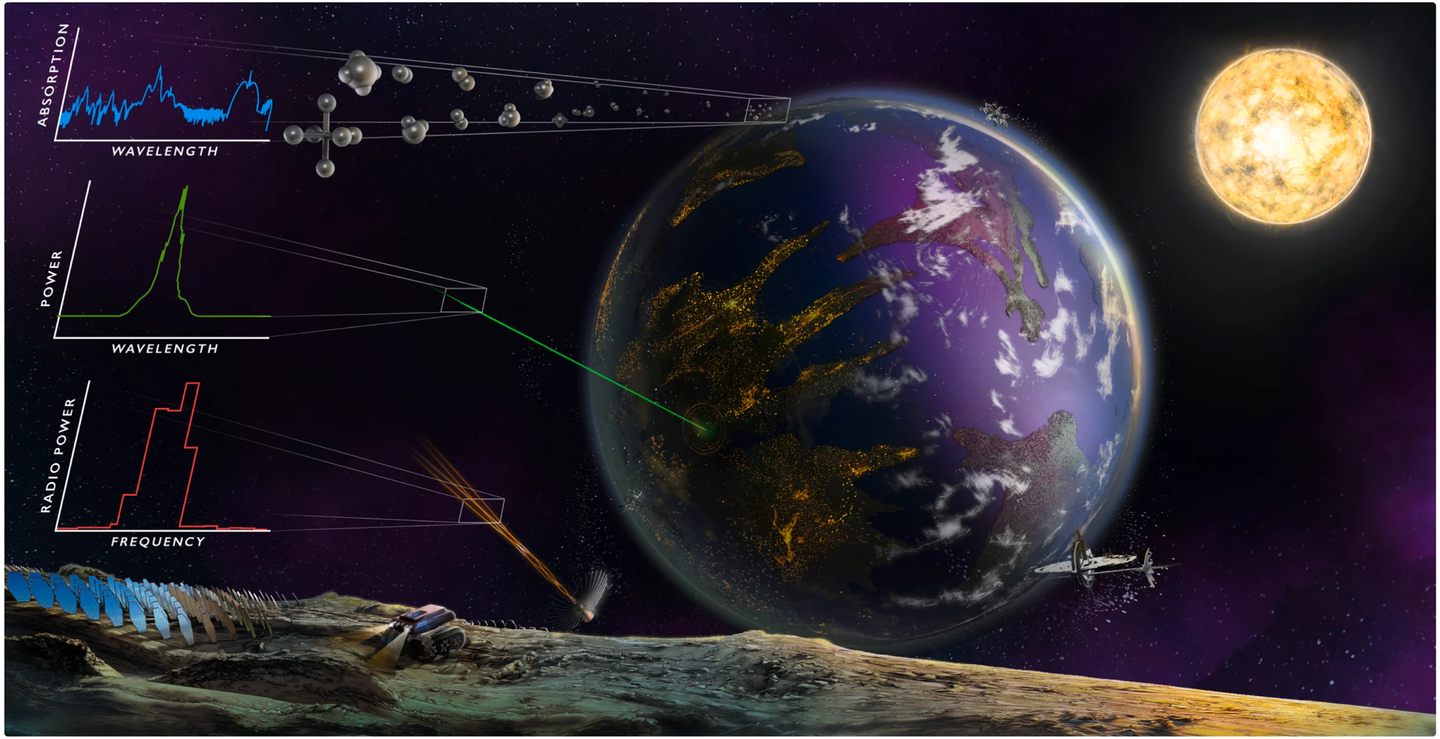

A terraformed planet has been artificially modified to support life. The study shows that these gases could be identified even at low concentrations in the atmospheres of planets outside our solar system using existing technology like the James Webb Space Telescope or a proposed European space telescope.

While controlling these gases is crucial on Earth to avoid harmful climate effects, they might be deliberately used on an exoplanet for beneficial reasons.

“For us, these gases are bad because we don’t want to increase warming. But they’d be good for a civilization that perhaps wanted to forestall an impending ice age or terraform an otherwise-uninhabitable planet in their system, as humans have proposed for Mars,” said Edward Schwieterman, a UCR astrobiologist and the lead author of the study.

These gases do not naturally occur in significant amounts, meaning they must be manufactured. Therefore, finding them would indicate intelligent, technology-using life forms. Such signs are known as technosignatures.

The five gases proposed by the researchers are used on Earth in industrial applications, such as making computer chips. They include fluorinated versions of methane, ethane, and propane, along with gases made of nitrogen and fluorine or sulfur and fluorine. Their advantages as terraforming gases are detailed in a new paper published in the Astrophysical Journal.

Related Stories

One significant advantage is their effectiveness as greenhouse gases. Sulfur hexafluoride, for example, has 23,500 times the warming power of carbon dioxide. Even a small amount could warm a freezing planet to the point where liquid water could exist on its surface.

Another advantage of these gases, from an alien perspective, is their longevity. In an Earth-like atmosphere, they could persist for up to 50,000 years. “They wouldn’t need to be replenished too often for a hospitable climate to be maintained,” Schwieterman explained.

Previously, refrigerant chemicals like CFCs were proposed as technosignature gases because they are almost exclusively artificial and visible in Earth’s atmosphere. However, CFCs are not ideal because they destroy the ozone layer. In contrast, the fully fluorinated gases discussed in the new paper are chemically inert and do not harm the ozone layer.

“If another civilization had an oxygen-rich atmosphere, they’d also have an ozone layer they’d want to protect,” Schwieterman said. “CFCs would be broken apart in the ozone layer even as they catalyzed its destruction.”

CFCs are also short-lived, making them harder to detect.

The fluorinated gases, on the other hand, absorb infrared radiation, which creates an infrared signature detectable by space-based telescopes. With current or planned technology, scientists could identify these chemicals in certain nearby exoplanetary systems.

“With an atmosphere like Earth’s, only one out of every million molecules could be one of these gases, and it would be potentially detectable,” Schwieterman said. “That gas concentration would also be sufficient to modify the climate.”

To arrive at this calculation, the researchers simulated a planet in the TRAPPIST-1 system, about 40 light-years away from Earth. This system, with its seven known rocky planets, is one of the most studied planetary systems aside from our own and a realistic target for existing space-based telescopes.

The research team also evaluated the European LIFE mission’s potential to detect fluorinated gases. The LIFE mission aims to directly image planets using infrared light, allowing it to target more exoplanets than the Webb telescope, which observes planets as they pass in front of their stars.

This research involved collaboration with Daniel Angerhausen at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology/PlanetS and researchers from NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, the Blue Marble Space Institute of Science, and Paris University.

While the likelihood of finding these gases soon is uncertain, the researchers are confident that if these gases exist, they can be detected during planned missions to study planetary atmospheres.

“You wouldn’t need extra effort to look for these technosignatures if your telescope is already characterizing the planet for other reasons,” Schwieterman said. “And it would be jaw-droppingly amazing to find them.”

Other members of the research team share enthusiasm for the potential of discovering signs of intelligent life and how current technology has brought us closer to this goal.

“Our thought experiment shows how powerful our next-generation telescopes will be. We are the first generation in history that has the technology to systematically look for life and intelligence in our galactic neighborhood,” added Angerhausen.

This research not only highlights the potential of current and future telescopes but also underscores humanity's quest to explore the cosmos and uncover its secrets.

Note: Materials provided above by the The Brighter Side of News. Content may be edited for style and length.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get the Brighter Side of News' newsletter.

Joshua Shavit

Science & Technology Writer | AI and Robotics Reporter

Joshua Shavit is a Los Angeles-based science and technology writer with a passion for exploring the breakthroughs shaping the future. As a contributor to The Brighter Side of News, he focuses on positive and transformative advancements in AI, technology, physics, engineering, robotics and space science. Joshua is currently working towards a Bachelor of Science in Business Administration at the University of California, Berkeley. He combines his academic background with a talent for storytelling, making complex scientific discoveries engaging and accessible. His work highlights the innovators behind the ideas, bringing readers closer to the people driving progress.