Archeologists discover the first stone toolmakers from 2.9 million years ago

Archaeologists discover 2.9-million-year-old Oldowan stone tools in Kenya, revealing early human ancestors’ use of technology.

Nyayanga site being excavated in July 2016. (CREDIT: J.S. Oliver, Homa Peninsula Paleoanthropology Project)

Archaeologists have uncovered some of the oldest stone tools ever found, shedding light on how early humans and their relatives adapted to their environment.

A remarkable excavation near Lake Victoria in Kenya has revealed hundreds of tools and fossils, dating back as far as three million years. These discoveries provide some of the earliest evidence of hominins using tools to butcher large animals and process plant materials.

Unearthing Early Innovation

The artifacts, found at a site called Nyayanga on the Homa Peninsula, were excavated over several field seasons beginning in 2015. A local worker initially noticed stone tools and animal fossils eroding from the soil.

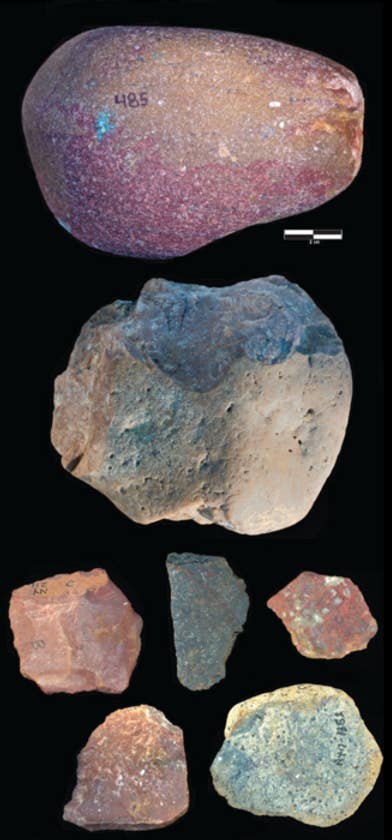

Archaeologists later recovered 330 artifacts, including 42 Oldowan tools—primitive instruments used for cutting, scraping, and pounding. These tools were discovered near the butchered remains of at least three hippos, some bearing cut marks, and alongside a pair of ancient molars belonging to Paranthropus, a close evolutionary relative of modern humans.

Associate Professor Julien Louys, from Griffith University’s Australian Research Centre for Human Evolution, was part of a large team of researchers led by scientists with the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History and Queens College, City University of New York, as well as the National Museums of Kenya, Liverpool John Moores University and the Cleveland Museum of Natural History.

The artifacts were dated between 2.6 and 3 million years old, making them some of the oldest Oldowan tools ever found. This discovery extends the known timeline of large-animal butchering by at least 600,000 years.

Analysis of wear patterns on the tools indicates they were used for cutting meat, breaking bones to extract marrow, and processing plants such as tubers.

Who Made the Tools?

The presence of Paranthropus teeth near the tools has sparked debate about whether this hominin lineage, rather than early members of the Homo genus, was responsible for their creation. Historically, scientists believed only Homo species crafted stone tools, but the findings challenge that assumption.

Related Stories

"The assumption among researchers has long been that only the genus Homo, to which humans belong, was capable of making stone tools," said Rick Potts, a paleoanthropologist from the Smithsonian's National Museum of Natural History. "But finding Paranthropus alongside these stone tools opens up a fascinating whodunnit."

Not everyone is convinced. Some researchers argue that Paranthropus had strong jaws adapted for chewing tough plant matter, reducing its need for tools.

Despite the uncertainty, the discovery of Oldowan tools alongside Paranthropus remains raises intriguing questions about early technological development and how multiple hominin species might have influenced toolmaking traditions.

The Significance of Oldowan Technology

Oldowan tools represent a major evolutionary step in early human technology. They include hammerstones, cores, and flakes, which were systematically shaped to perform specific tasks. These tools were a significant improvement over older, cruder implements like those found at Lomekwi 3, a 3.3-million-year-old site in northern Kenya.

Unlike their predecessors, Oldowan tools were produced using "freehand percussion," where a core stone was held in one hand and struck with a hammerstone in the other. This technique required greater dexterity and planning.

“With these tools, you can crush better than an elephant’s molar and cut better than a lion’s canine,” Potts explained. “Oldowan technology was like suddenly evolving a brand-new set of teeth outside your body.” These tools made a wider range of foods accessible, allowing early hominins to consume not just fruits and leaves but also meat and underground plant parts, such as roots and tubers.

A New Perspective on Early Human Life

The Nyayanga discoveries expand the known range of early tool use far beyond previous finds. Earlier Oldowan tools had been found 800 miles away in Ethiopia and were dated to 2.6 million years ago. Unlike those, the newly unearthed tools were found alongside clear evidence of use—animal bones bearing cut marks and plant residues on tool surfaces.

The excavation site also highlights the changing environment that shaped early human evolution. Potts describes East Africa at the time as a "boiling cauldron of environmental change," marked by alternating periods of drought and heavy rains. The ability to use stone tools would have provided a critical survival advantage, allowing hominins to exploit diverse food sources and adapt to shifting landscapes.

Microscopic analysis of the tools showed they were used for cutting meat, scraping plant material, and pounding both animal and vegetable matter. Since fire would not be harnessed for cooking for another two million years, early hominins likely consumed raw meat and plants, possibly tenderizing food by pounding it.

The discoveries at Nyayanga contribute to a broader understanding of human origins. They provide a glimpse into how early hominins interacted with their environment and how their technological innovations helped them thrive.

Whether the tools were crafted by members of the Homo genus or their evolutionary cousins, the findings suggest that multiple hominin species may have played a role in developing stone technology.

“This is one of the oldest, if not the oldest, examples of Oldowan technology,” said Thomas Plummer of Queens College, a co-author of the study. “This shows the toolkit was more widely distributed at an earlier date than people realized, and that it was used to process a wide variety of plant and animal tissues.”

The study, published in Science, was supported by the Smithsonian, the Leakey Foundation, the National Science Foundation, and other research institutions. These findings reshape our understanding of early technological evolution and raise new questions about who first wielded these stone tools and how they shaped the course of human history.

Note: Materials provided above by The Brighter Side of News. Content may be edited for style and length.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News' newsletter.

Joseph Shavit

Head Science News Writer | Communicating Innovation & Discovery

Based in Los Angeles, Joseph Shavit is an accomplished science journalist, head science news writer and co-founder at The Brighter Side of News, where he translates cutting-edge discoveries into compelling stories for a broad audience. With a strong background spanning science, business, product management, media leadership, and entrepreneurship, Joseph brings a unique perspective to science communication. His expertise allows him to uncover the intersection of technological advancements and market potential, shedding light on how groundbreaking research evolves into transformative products and industries.