Archaeologists locate the lost site depicted in the Bayeux Tapestry

Archaeologists uncover the lost residence of King Harold, revealing Anglo-Saxon power centers before the Norman Conquest.

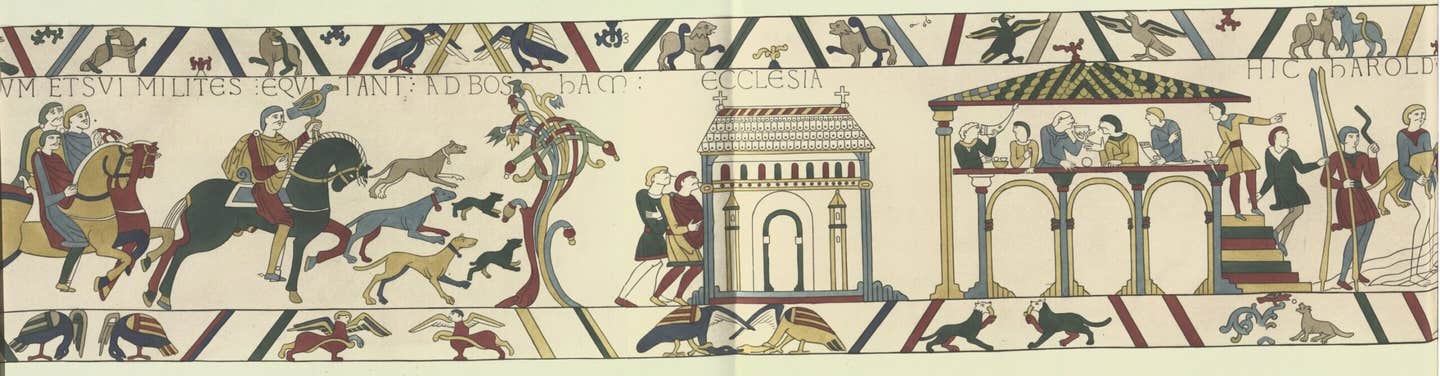

The Bayeux Tapestry, showing King Harold riding to Bosham, where he attends church and feasts in a hall, before departing for France. The Society of Antiquaries of London. (CREDIT: The Society of Antiquaries of London)

The towering castles that dot England’s landscape symbolize power, conquest, and control. For centuries, they have been viewed as monuments to the Norman elite who reshaped the country after 1066. However, the grand estates and fortified structures that came before the Norman Conquest have often been overlooked.

New research sheds light on the aristocratic power centers that existed before the arrival of William the Conqueror, challenging long-held assumptions about medieval England.

Castles and the Norman Influence

In the 12th century, historian William of Malmesbury described how the English lived in simple houses while the Normans and French resided in noble mansions. This perception of Norman superiority in architecture and defense has persisted for centuries.

The Normans introduced castles, revolutionizing England’s military and social structures. The word “castle” itself first appeared in English records in 1051, when foreign builders erected a fortification in Herefordshire. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle described the structure as alien, emphasizing its disruptive presence.

However, the idea that castles marked an abrupt break from the past is a modern interpretation. The Normans did not introduce fortifications to England; they transformed existing traditions of aristocratic architecture.

Before their arrival, English noble estates functioned as centers of power, integrating residential, economic, and religious elements. These sites, enclosed by defensive structures, served as visible expressions of wealth and status.

Pre-Conquest Power Centers

Long before the Normans built their castles, England’s aristocracy had established their own fortified sites. These residences were hubs of power where lords controlled land, managed resources, and reinforced their status.

Related Stories

By the 10th century, wealth and influence were measured not only by military strength but by the ability to construct grand homes that combined defensive, religious, and residential functions.

Archaeological evidence reveals that Anglo-Saxon elites enclosed their estates with earthworks and ditches, much like the later Norman castles. Places like Trowbridge in Wiltshire and Faccombe Nethercombe in Hampshire exhibit these fortified layouts. Some sites even incorporated early versions of moats. The transition from these earlier noble estates to Norman castles was gradual, rather than a sudden revolution.

While castles remain the dominant focus of medieval studies, historians and archaeologists have recently turned their attention to these earlier power centers.

The shift from kin-based aristocratic authority to a system built around personal wealth in the 10th century reshaped England’s landscape. Sites that combined grand halls, churches, and agricultural estates became essential symbols of status.

The Rediscovery of Harold Godwinson’s Estate

Recent excavations in Bosham, West Sussex, have uncovered what is believed to be the lost residence of Harold Godwinson, England’s last Anglo-Saxon king. The Bayeux Tapestry, which depicts the events of 1066, shows Harold feasting in an opulent hall at Bosham before departing for France. However, the exact location of this estate had remained uncertain.

A team from Newcastle University and the University of Exeter revisited previous excavations and conducted new surveys to trace the site’s history.

Their findings, published in The Antiquaries Journal, suggest that a private home in Bosham stands on the remains of Harold’s estate. The discovery of a medieval latrine within a timber building—an early sign of elite housing—was a crucial piece of evidence.

By the 10th century, high-status residences began incorporating toilets, setting them apart from common dwellings. The presence of a church within the estate further reinforced its significance as a center of power.

Dr. Duncan Wright, the lead archaeologist, explained, “The realization that the 2006 excavations had found, in effect, an Anglo-Saxon en-suite confirmed to us that this house sits on the site of an elite residence pre-dating the Norman Conquest.”

His colleague, Professor Oliver Creighton, added, “The Norman Conquest saw a new ruling class supplant an English aristocracy that has left little in the way of physical remains, which makes the discovery at Bosham hugely significant—we have found an Anglo-Saxon show-home.”

Rethinking England’s Medieval Past

The research at Bosham is part of a broader initiative called “Where Power Lies,” funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council. This project aims to map and analyze aristocratic sites across England between 800 and 1200 AD. By studying these locations, historians hope to bridge the divide between pre- and post-Conquest aristocratic estates, recognizing continuity rather than stark contrast.

For centuries, scholars have focused on castles as the defining feature of medieval power, often viewing Anglo-Saxon estates as mere precursors. However, evidence suggests that the Norman Conquest accelerated changes that were already underway, rather than introducing an entirely new system. The arrival of the Normans undoubtedly reshaped England’s ruling class, but native elites adapted, finding opportunities within the new hierarchy.

Despite their historical importance, many Anglo-Saxon power centers remain understudied. The fragmented nature of medieval studies—where historians and archaeologists often work in isolation—has contributed to this gap. The “Where Power Lies” project seeks to change this by providing a national survey of noble residences, offering fresh insights into how power was expressed and maintained across centuries.

The discovery at Bosham challenges the notion that the Normans introduced elite residences to England. Instead, it reveals a deeper history of aristocratic life, one that extends beyond castles and into the grand halls of the Anglo-Saxon nobility.

By reevaluating these forgotten sites, researchers are uncovering a more nuanced picture of England’s medieval past—one where power lay not just in stone fortresses but in the estates of lords who shaped the country long before 1066.

Note: Materials provided above by The Brighter Side of News. Content may be edited for style and length.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News' newsletter.

Joshua Shavit

Science & Technology Writer | AI and Robotics Reporter

Joshua Shavit is a Los Angeles-based science and technology writer with a passion for exploring the breakthroughs shaping the future. As a contributor to The Brighter Side of News, he focuses on positive and transformative advancements in AI, technology, physics, engineering, robotics and space science. Joshua is currently working towards a Bachelor of Science in Business Administration at the University of California, Berkeley. He combines his academic background with a talent for storytelling, making complex scientific discoveries engaging and accessible. His work highlights the innovators behind the ideas, bringing readers closer to the people driving progress.