Ancient Roman boundary stone sheds light on biblical ownership and taxation

Rare Roman boundary stone reveals ancient land ownership, settlement history, and Diocletian’s tax reforms in northern Israel.

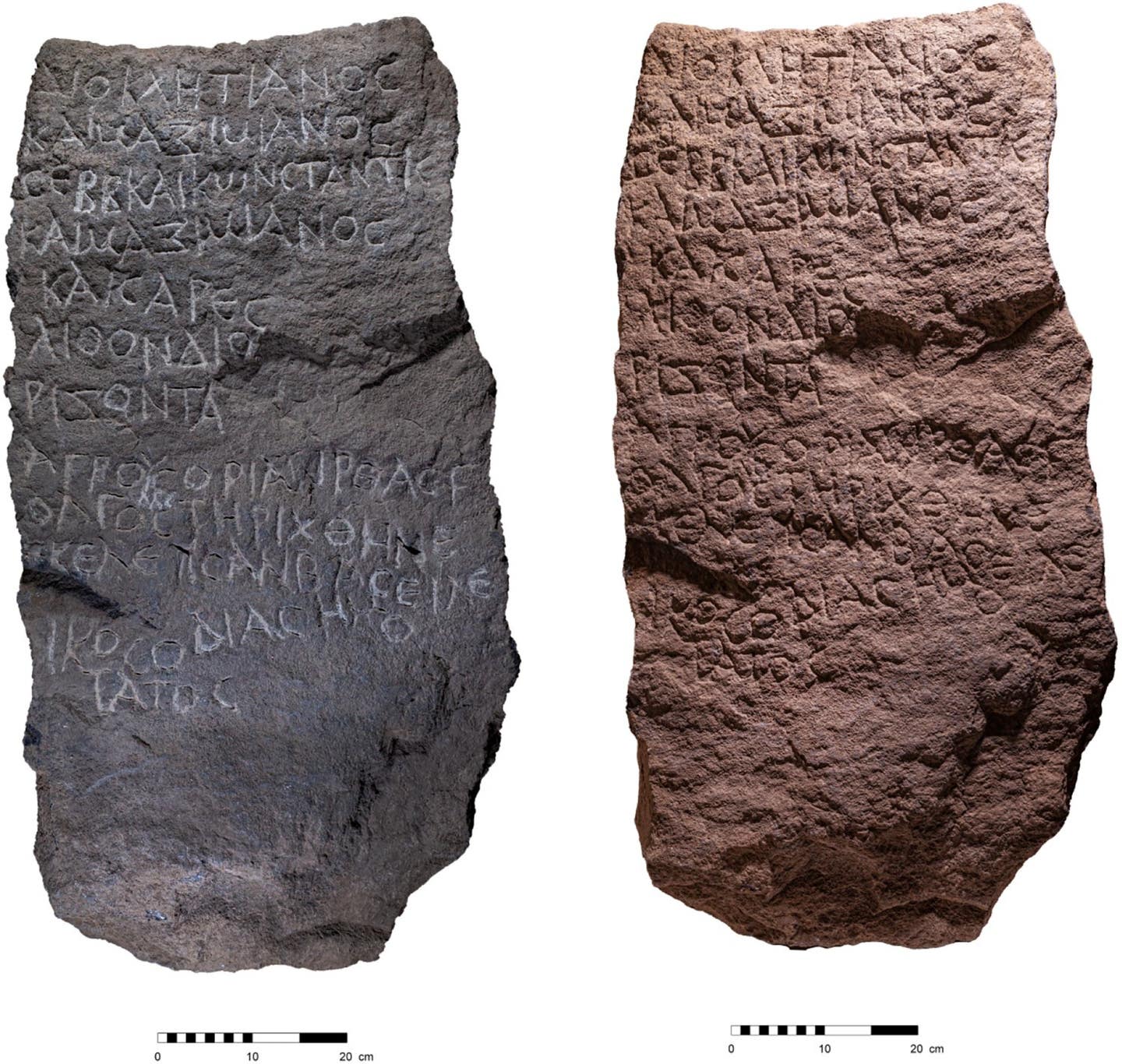

Diocletian and Maximian Augusti, and Constantius and Maximian, Caesars, have ordered this stone to be set up, marking boundaries of fields of Tirthas (and) Golgol/m; Baseileikos, vir perfectissimus (supervised). The inscription, with and without highlighting of the letters (CREDIT: T. Rogovski)

Archaeologists have uncovered a fascinating relic of ancient administrative practices during excavations at Abel Beth Maacah, a site in northern Israel rich with historical significance.

This discovery—a Tetrarchic boundary stone—dates back to the Roman Empire under Emperor Diocletian and sheds new light on land ownership, settlement patterns, and imperial taxation in the region nearly 1,700 years ago.

Found reused as a cover for a Mamluk-period grave, the basalt slab bears an inscription in Greek that offers rare insights into the socio-economic landscape of the Roman Near East.

Unearthing an Ancient Landmark

The excavation team, led by experts from the Hebrew University and Azusa Pacific University, uncovered the boundary stone during their 2022 field season. Measuring over a meter in length and weighing several hundred kilograms, the slab originally stood upright to mark the borders of agricultural fields.

Its inscription reveals the names of Roman emperors Diocletian and Maximian, as well as their successors Constantius and Galerius, reflecting the hierarchical governance structure established under the Tetrarchy in 293 CE.

While the stone’s original location remains unknown, its proximity to the findspot suggests it was not moved far. The meticulous engraving provides details about an imperial surveyor, or "censitor," named Baseilikos, whose identity had not been recorded until now.

This surveyor likely played a key role in implementing Diocletian’s sweeping tax reforms, which aimed to systematize land ownership and taxation across the empire.

New Insights into Roman Geography

A particularly exciting aspect of this discovery is the mention of two previously unknown village names: Tirthas and Golgol. These toponyms may correspond to sites identified in the 19th-century Survey of Western Palestine.

Related Stories

Tirthas is thought to match Kh. Turritha, a site marked by basalt stone heaps along the Hasbani River. Golgol, meanwhile, evokes the Hebrew root GLGL, meaning "to roll," and could describe a nearby round hill now called Tell ‘Ajul.

The inscription also contains linguistic curiosities. For example, it pairs the terms "fields" and "boundaries," which are usually separate on similar stones. This anomaly may reflect a grammatical influence from Semitic languages or an error by the engraver. These nuances, along with corrections made to misspelled place names, hint at the challenges faced by those tasked with creating these enduring markers of Roman authority.

Context and Significance

This boundary stone joins a corpus of over 40 similar artifacts found across the Hula Valley, the Golan, and surrounding regions. These stones marked the borders between villages or fields and were instrumental in Diocletian’s efforts to reform land taxation.

Unlike earlier systems that tied taxes to urban centers, Diocletian’s reforms required small landholders to pay taxes directly to the empire. This shift underscores the economic independence of rural communities and the intricate relationship between imperial policies and local livelihoods.

“This discovery is a testament to the meticulous administrative reorganization of the Roman Empire during the Tetrarchy,” said Professor Uzi Leibner of the Hebrew University. “Finding a boundary stone like this not only sheds light on ancient land ownership and taxation but also provides a tangible connection to the lives of individuals who navigated these complex systems nearly two millennia ago.”

Dr. Avner Ecker, who helped decipher the inscription, emphasized its broader implications: “What makes this find particularly exciting is the mention of two previously unknown place names and a new imperial surveyor. It underscores how even seemingly small discoveries can dramatically enhance our understanding of the socio-economic and geographic history of the region.”

Bridging History and Archaeology

The abundance of boundary stones in the northern Hula Valley reflects the region’s agricultural importance during the Roman period. Scholars suggest that the high concentration of small landholders in this area contributed to its unique socio-economic dynamics.

Remarkably, rabbinic sources from the same era reference burdens imposed by Diocletian’s tax reforms, highlighting the challenges faced by local communities under imperial rule.

This particular stone’s placement on a hilltop rather than in the fields below adds to its intrigue. The elevated location may have served as a prominent landmark, visible across the surrounding valley. Nearby, the archaeological record hints at a complex settlement history, with evidence of Roman, Byzantine, and Ottoman-era activity.

The discovery also raises questions about the fate of these ancient villages. Neither Tirthas nor Golgol appears in Ottoman land tax records from the 16th century, suggesting that these sites were likely abandoned long before. This pattern aligns with broader trends in the region, where many Roman-era settlements were deserted during the transition to Byzantine and Early Islamic periods.

Boundary stones like this one offer a rare glimpse into the interplay of geography, governance, and daily life in antiquity. They reveal not only the administrative reach of the Roman Empire but also the resilience of local communities adapting to imperial demands. For modern researchers, each stone is a puzzle piece, helping to reconstruct the economic and social fabric of a bygone era.

“This exceptional artifact now joins the broader narrative of Roman imperial administration in the Levant,” said Professor Leibner. “It enriches our understanding of how ancient societies functioned and how their stories continue to resonate through the archaeological record.”

With its rich inscription, the Abel Beth Maacah boundary stone stands as a testament to the enduring legacy of Roman engineering and governance. Its discovery not only deepens our appreciation for the complexities of ancient land management but also highlights the ongoing importance of archaeology in uncovering the past.

Note: Materials provided above by The Brighter Side of News. Content may be edited for style and length.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News' newsletter.

Rebecca Shavit

Science & Technology Journalist | Innovation Storyteller

Based in Los Angeles, Rebecca Shavit is a dedicated science and technology journalist who writes for The Brighter Side of News, an online publication committed to highlighting positive and transformative stories from around the world. With a passion for uncovering groundbreaking discoveries and innovations, she brings to light the scientific advancements shaping a better future. Her reporting spans a wide range of topics, from cutting-edge medical breakthroughs and artificial intelligence to green technology and space exploration. With a keen ability to translate complex concepts into engaging and accessible stories, she makes science and innovation relatable to a broad audience.