Ancient human fossils reveal a startling twist in evolutionary history

The Juluren show a blend of traits seen in Neanderthals but not in Denisovans, Homo erectus, or modern humans.

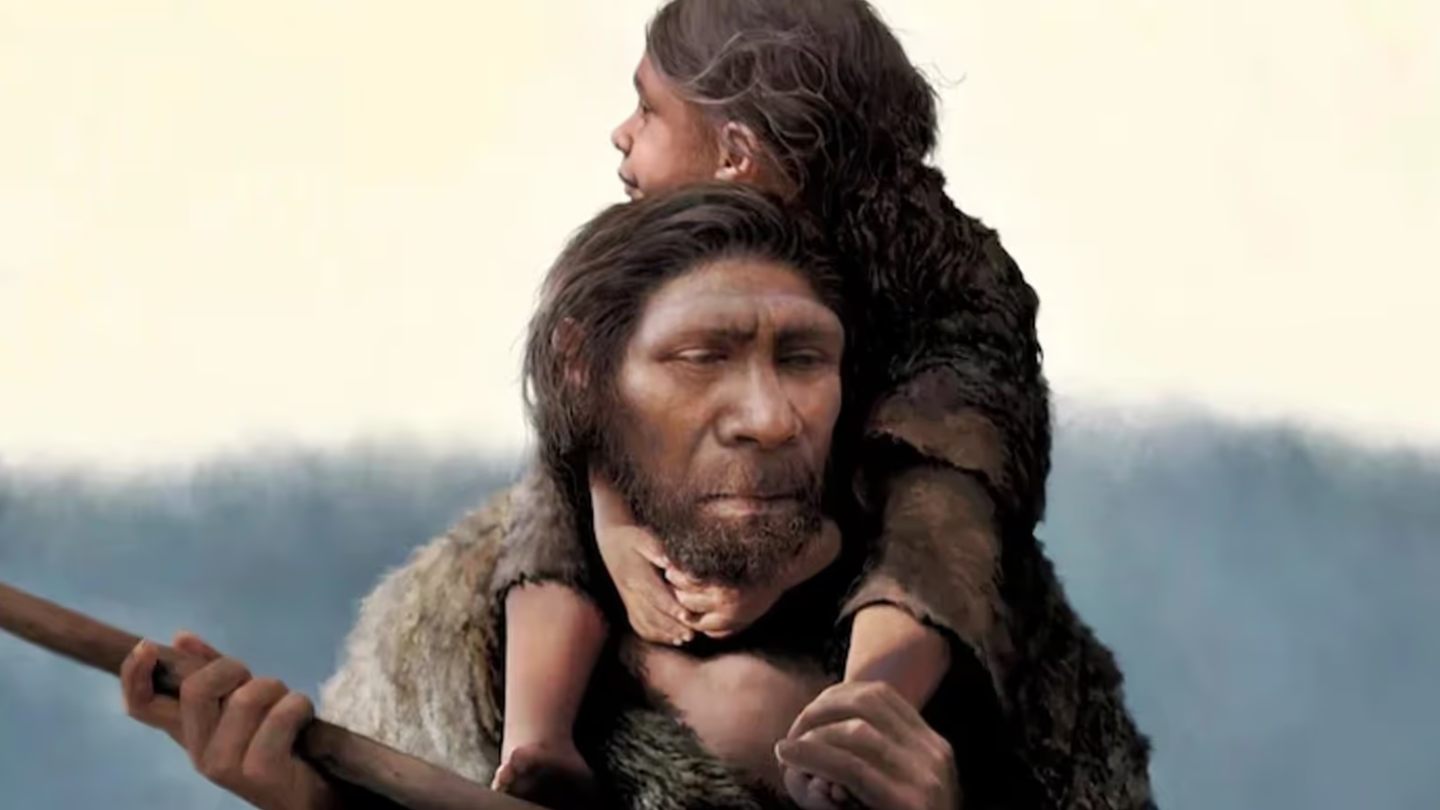

Over 100,000 years ago, a mysterious group of ancient humans walked the lands of eastern Asia. (CREDIT: Tom Bjorklund)

Over 100,000 years ago, a mysterious group of ancient humans walked the lands of eastern Asia. Known as the Juluren—meaning “large head people”—they’ve recently been introduced to science under the name Homo juluensis. These early humans are unlike any other group ever found.

What sets the Juluren apart isn’t just their strange mix of traits. It's their unusually large brains, some over 1,700 cubic centimeters. That’s bigger than most ancient humans—and even many of us today. These features are forcing scientists to rethink how human evolution unfolded, especially in places long overlooked.

Paleoanthropologists Xiujie Wu and Christopher Bae say this group doesn’t fit the usual mold. The Juluren show a blend of traits seen in Neanderthals but not in Denisovans, Homo erectus, or modern humans. Their facial structures and jaws tell a complex and surprising story.

For years, Asian fossils that didn’t match familiar categories were swept under broad labels like “Denisovans.” Wu and Bae argue this misses the point. These fossils, they say, belong to a distinct group with its own role in the human family tree.

The Juluren lived between 300,000 and 50,000 years ago. That means they shared the planet with early Homo sapiens. Their presence adds a new layer to the picture of human life during this time. And their brain size hints at capacities we haven’t yet understood.

Anthropologist John Hawks called the research “provocative.” He said there’s still a lot to uncover about Asia’s role in human evolution. By naming the group Juluren, researchers are giving these people a rightful place in our shared story.

For a long time, scientists treated eastern Asia as a dead end in evolution. The common view was that Homo erectus stuck around there too long, using simple tools and making little progress. But those ideas have started to fall apart.

Findings from the Middle Pleistocene suggest the opposite. This region wasn’t lagging behind—it was alive with change. The Juluren help prove that. Their discovery shows that the roots of humanity stretch farther, and deeper, than we once thought.

Related Stories

Chinese scientists, including Xinzhi Wu and Lanpo Jia, challenged these outdated views. They proposed a “river network” model of human evolution, where populations diverged and merged across Africa and Eurasia. This idea of genetic exchanges and regional continuity forms the basis for understanding the Juluren and their place in history.

Recent advances in dating techniques, such as cosmogenic burial aging, U-series-ESR, and optically stimulated luminescence (OSL), have refined the chronology of these fossils. Genetic studies have also transformed our understanding, especially those from Denisova Cave in Central Asia.

Yet, the anatomical variation of Denisovans remains mostly unknown, leaving researchers to ponder which fossils truly represent this enigmatic group. Wu and Bae’s work shifts the focus to fossils from northern and central China, particularly from the Xujiayao and Xuchang sites, which they suggest may belong to the Juluren.

The Xujiayao site, located in the Nihewan Basin of northern China, has yielded over 10,000 stone artifacts and 21 hominin fossils since its discovery in 1974. These fossils date to between 250,000 and 130,000 years ago and include fragments of skulls and teeth.

The most complete skull, Xujiayao 6, reveals a cranial capacity of 1700 milliliters, the largest of its time. While its size rivals modern humans, its shape is markedly different, with a broader base and lower height.

Other fossils from Xujiayao, such as a child’s upper jaw (Xujiayao 1), offer insights into dental patterns. These teeth display a mix of traits seen in both Neanderthals and earlier Asian hominins. For example, the shovel-shaped incisors resemble those from Zhoukoudian, while their curvature hints at Neanderthal-like traits. Researchers have also noted similarities in molar root structure and development patterns with modern humans.

Further south, the Xuchang site in Henan Province has contributed two key fossils, Xuchang 1 and 2, dating to between 125,000 and 105,000 years ago. These skulls reveal even larger cranial capacities—1800 milliliters in Xuchang 1—exceeding most living humans and Neanderthals.

Despite their size, these skulls lack the high, rounded shape of modern humans, sharing some traits with Neanderthals, such as a suprainiac fossa, a small depression at the back of the skull.

Together, the Xujiayao and Xuchang fossils present a mosaic of traits that challenge traditional classifications. Some characteristics link them to Neanderthals, while others suggest connections to Denisovans or earlier Asian populations. The diversity within these fossils reflects the complexity of human evolution in eastern Asia, where interbreeding and migration likely played significant roles.

The Juluren’s distinct features also raise questions about their relationship to the Denisovans. Fossils identified as Denisovans, such as those from Denisova Cave and the Xiahe mandible from Baishiya Karst Cave, share some traits with the Xujiayao and Xuchang specimens.

Large, complex molars and robust jaw structures suggest possible connections, but significant differences remain. Wu and Bae propose that the Juluren represent a unique population shaped by genetic exchanges between Asian Homo erectus, Neanderthals, and other ancient groups.

Names like “Denisovan” and “Juluren” are critical for organizing our understanding of ancient human groups. The term “Denisovan,” coined after genetic analysis of a finger bone from Denisova Cave, has become a catch-all for diverse populations across Asia and the Pacific. However, this broad label obscures the complexity of their evolutionary history.

Genetic evidence reveals deep divergences within Denisovan populations, some dating back 350,000 years. The Juluren’s distinct anatomy and evolutionary timeline warrant a separate designation, even if they share common ancestry with Denisovans.

Naming these groups also helps clarify their cultural and ecological contexts. The Xujiayao and Xuchang fossils reflect lives shaped by varying environmental pressures, tools, and social behaviors.

Their large brain sizes hint at advanced cognitive abilities, but their fragmented fossil record limits definitive conclusions. As Wu and Bae emphasize, these groups likely represent a dynamic network of populations that mixed and adapted over millennia.

The discovery of the Juluren underscores the complexity of human evolution and challenges the idea of linear progress. Instead, the human story appears as a tangled web of migrations, interactions, and adaptations.

As new technologies and discoveries refine our understanding, names like Juluren provide valuable tools for navigating this intricate history. The large head people, with their unique combination of traits, remind us of the diversity that has always defined humanity.

Note: Materials provided above by The Brighter Side of News. Content may be edited for style and length.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News' newsletter.

Joshua Shavit

Science & Technology Writer | AI and Robotics Reporter

Joshua Shavit is a Los Angeles-based science and technology writer with a passion for exploring the breakthroughs shaping the future. As a contributor to The Brighter Side of News, he focuses on positive and transformative advancements in AI, technology, physics, engineering, robotics and space science. Joshua is currently working towards a Bachelor of Science in Business Administration at the University of California, Berkeley. He combines his academic background with a talent for storytelling, making complex scientific discoveries engaging and accessible. His work highlights the innovators behind the ideas, bringing readers closer to the people driving progress.