Ancient circular burial site found to be much older than Stonehenge

New dating of the Flagstones site shows it predates Stonehenge by 200 years, reshaping ideas about Neolithic Britain.

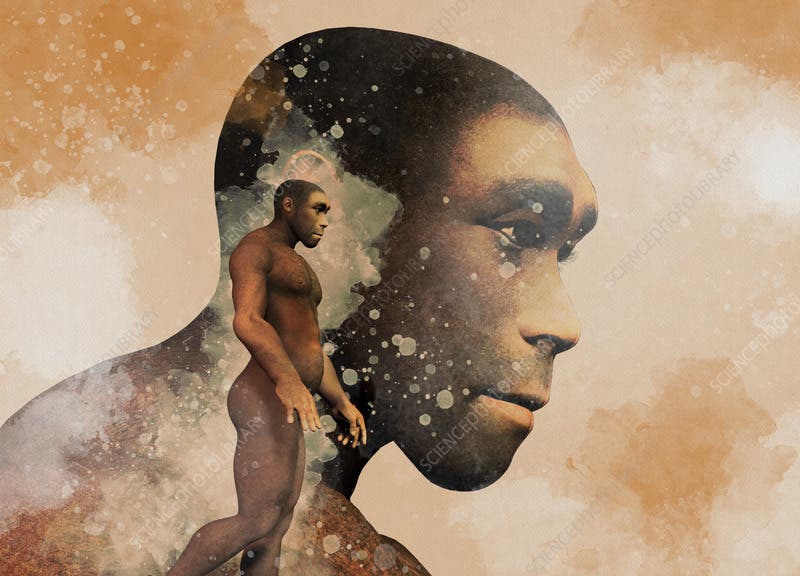

Flagstones enclosure seen shortly after construction in the middle Neolithic period. (CREDIT: Reconstruction by Jennie Anderson)

In the green hills of southwest Britain, a quiet revolution took place over 5,000 years ago. Long before Stonehenge rose from the plains of Wiltshire, people were already shaping the land into sacred circles. The circular enclosure at Flagstones near Dorchester may be the oldest of its kind in Britain, and it’s rewriting what archaeologists thought they knew about how the Neolithic world transformed.

Thanks to new radiocarbon dating, Flagstones has now been dated to around 3200 BC—about 200 years earlier than previously believed. This new timeline positions it as a key monument during the Middle Neolithic, a time of major cultural and ceremonial change. The site’s deep age and unusual design suggest it could have influenced later famous landmarks, like the first phase of Stonehenge.

The Rise of Round Monuments

During the Middle Neolithic, from about 3400 to 2800 BC, builders in Britain and Ireland began moving away from long, rectangular structures like barrows and cursus monuments. They started building large circular enclosures, called proto-henges or formative henges. These new forms were striking: wide circles ranging from 80 to 110 meters in diameter, typically marked by ditches, banks, and narrow entrances.

While these early henges don’t always contain much pottery or flint, they do reveal strong ceremonial purposes. Excavations at several sites have uncovered cremated remains and inhumed bodies, often buried with care in specially dug pits. These practices hint at changing views on death, space, and ritual.

The transition to building circles instead of lines wasn’t just a shift in shape—it reflected deeper cultural changes. Ritual deposits of animal bone and other materials in ditches point back to older customs at causewayed enclosures. But the cleaner, more segmented layouts at proto-henges also suggest something new: a growing interest in order, symmetry, and perhaps a more centralized form of ceremony.

Digging into Flagstones’ Secrets

The Flagstones enclosure stands out not just for its age, but for its form and the story it tells. Hidden beneath Thomas Hardy’s former home, Max Gate, and partly under the modern Dorchester bypass, this site went unnoticed for centuries until construction work in the 1980s revealed its buried mystery. What archaeologists found was a nearly perfect 100-meter-wide circle, formed by intercutting pits, with evidence suggesting an outer and inner bank.

Related Stories

Unlike many other early enclosures, Flagstones was carved into chalk bedrock with care and complexity. Some of the pits held burials—a cremated adult placed beneath a large sarsen stone, and three uncremated children, one covered with a limestone slab. Other cremations, buried in a ring-shaped ditch, added to the monument's solemn use as a burial ground.

At first, researchers believed Flagstones had been built around 3000 BC, close in age to the early phase of Stonehenge. But only six radiocarbon dates existed for the site, most taken from material unearthed in the 1980s.

That changed recently when Dr. Susan Greaney, an expert in Neolithic and Bronze Age monuments at the University of Exeter, and Dr. Peter Marshall, formerly with Historic England, led a new scientific dating program. Their team worked with labs at ETH Zürich and the University of Groningen to obtain 23 new radiocarbon measurements from human remains, red deer antlers, and charcoal.

The results surprised everyone.

Early activity on the site—such as pit digging—dates back to around 3650 BC. Then, after a long gap, the large circular enclosure was built around 3200 BC. Soon after, burials were placed in the pits.

But the most astonishing discovery came from the center of the monument: the grave of a young adult male, buried beneath a massive sarsen stone about 1,000 years after the enclosure’s original use. This unexpected reuse hints that Flagstones remained an important or sacred site for many centuries.

A Monument Ahead of Its Time

Comparing Flagstones with other sites shows just how unusual—and ahead of its time—it was. The first phase of Stonehenge, a similarly circular enclosure, wasn’t built until around 2900 BC. Yet the designs are so similar that researchers now wonder if Flagstones might have served as a model.

“The chronology of Flagstones is essential for understanding the changing sequence of ceremonial and funeral monuments in Britain,” says Dr. Greaney. “The ‘sister’ monument to Flagstones is Stonehenge, whose first phase is almost identical, but it dates to around 2900 BC. Could Stonehenge have been a copy of Flagstones? Or do these findings suggest our current dating of Stonehenge might need revision?”

These questions matter because they reshape our view of how ideas and building styles spread. Flagstones might not have stood alone. It shares key traits with other monuments, like Llandygái ‘Henge’ A in Gwynedd, Wales. There, researchers also found cremated remains in a segmented enclosure. Together, these sites reflect a broader network of ceremonial spaces across Britain.

Even more intriguing is the possibility that this network extended beyond Britain. Artifacts and burial customs at Flagstones hint at ties to Ireland, suggesting that communities across the Irish Sea were sharing ideas.

The similarities in monument shape, burial style, and ritual practice point to a connected world, where people influenced each other’s beliefs and behaviors across wide distances.

Why Chronology Matters

Getting the timeline right is more than a matter of dates—it’s about understanding how people lived, thought, and remembered. With better radiocarbon dating and modeling, archaeologists are now able to place sites like Flagstones more accurately within broader cultural shifts.

Other major monuments in the Dorchester area, like the Mount Pleasant henge and the causewayed enclosure at Maiden Castle, are already well dated. Maiden Castle’s ditch was cut between 3660 and 3525 BC, while Mount Pleasant was built between 2615 and 2495 BC. Flagstones sits in between, helping bridge the gap in ceremonial styles between older linear enclosures and later monumental henges.

The updated chronology shows that Flagstones was not just a local experiment—it was part of a larger wave of innovation. It marks a point in time when builders began thinking in circles, not lines, and when death was honored in new and lasting ways.

Even though much of Flagstones now lies under a modern road, its legacy continues to grow. The site is a scheduled monument, with excavation archives preserved at the Dorset Museum. And the questions it raises—about tradition, influence, and memory—remain at the heart of research into Britain’s prehistoric past.

Thanks to this new research, the oldest known large circular enclosure in Britain is no longer just a footnote. It’s a landmark.

Research findings are available online in the journal Cambridge University Press.

Note: The article above provided above by The Brighter Side of News.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News' newsletter.

Rebecca Shavit

Science & Technology Journalist | Innovation Storyteller

Based in Los Angeles, Rebecca Shavit is a dedicated science and technology journalist who writes for The Brighter Side of News, an online publication committed to highlighting positive and transformative stories from around the world. With a passion for uncovering groundbreaking discoveries and innovations, she brings to light the scientific advancements shaping a better future. Her reporting spans a wide range of topics, from cutting-edge medical breakthroughs and artificial intelligence to green technology and space exploration. With a keen ability to translate complex concepts into engaging and accessible stories, she makes science and innovation relatable to a broad audience.