AI innovation fills in the missing gaps in ancient texts

A team of AI researchers has developed an AI application to help historians fill in the gaps of text missing from stone and metal artifacts

[Mar 13, 2022: Bob Yirka]

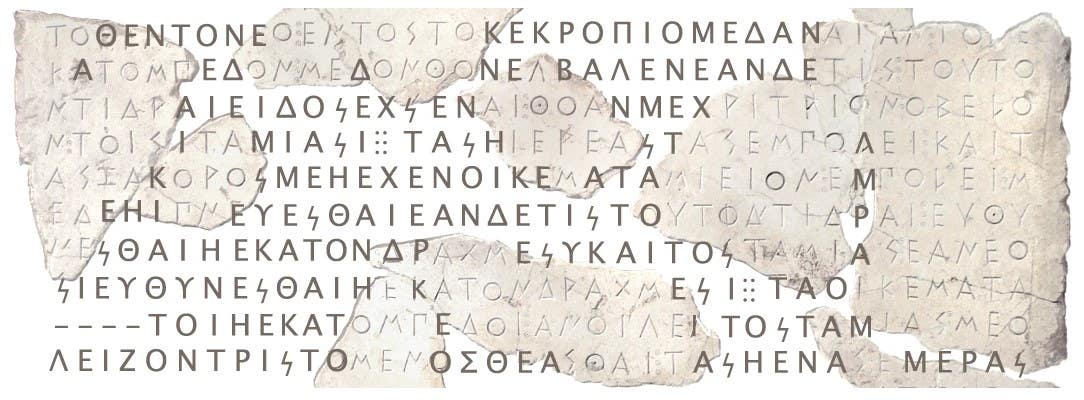

This inscription (Inscriptiones Graecae, volume 1, edition 3, document 4, face B (IG I3 4B)) records a decree concerning the Acropolis of Athens and dates to 485/4 BC. Marsyas, Epigraphic Museum. (CREDIT: WikiMedia CC BY 2.5.)

A team of AI researchers at DeepMind, working with colleagues from the University of Venice, the University of Oxford and Athens University of Economics and Business, has developed an artificial intelligence (AI) application to help historians fill in the gaps of text missing from stone, metal or pottery artifacts.

In their paper published in the journal Nature, the group describes how they built the app, how it can be used and how well it worked when tested against known texts. Charlotte Roueché, with King's College London, has published a News and Views piece in the same journal issue outlining the history of using new technology to better understand historical artifacts and the work done by the team on this new effort.

During certain points in history, humans began using written text for purposes such as keeping accounts. Such accounts can give modern scholars clues as to how people in ancient societies went about their days. But that is only if the artifacts can be deciphered. Many have been eroded by weather or have been broken and are missing pieces.

Modern scholars use a variety of tools to determine the content of the original text. This is almost always a long and tedious process. In this new effort, the team at DeepMind set out to develop a tool to help in such endeavors. The result was Ithaca, a machine-learning application that learns from other ancient texts to predict missing text.

Related Stories:

The researchers trained the application using 60,000 Greek texts from the years 700BC to 500AD. Each had already been extensively studied and reconstructed when necessary. The team then ran the app on the same texts prior to reconstruction. They then trained the app on another 8,000 well-studied texts to test it against the work done by human experts.

The researchers found the system to be 62% accurate, which was better than the performance of historians. But the best results came from collaborations between the AI system and the historians; together, they were able to achieve 72% accuracy.

This restored inscription (IG I3 4B) records a decree concerning the Acropolis of Athens and dates 485/4 BCE. (CREDIT: CC BY-SA 3.0, WikiMedia)

The researchers also added another feature—the ability to attribute a text to a time and place using clues found in the text and from other sources. They found the system to be 71% accurate in determining the origin of the writer and could place the date of writing to within 30 years, on average.

The study published in Nature is available here.

Note: Materials provided above by Bob Yirka. Content may be edited for style and length.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get the Brighter Side of News' newsletter.

Tags: #New_Innovations, #AI, #Language, #Research, #History, #Text, #Reconstruction, #Restoration, #Science, #The_Brighter_Side_of_News

Joseph Shavit

Head Science News Writer | Communicating Innovation & Discovery

Based in Los Angeles, Joseph Shavit is an accomplished science journalist, head science news writer and co-founder at The Brighter Side of News, where he translates cutting-edge discoveries into compelling stories for a broad audience. With a strong background spanning science, business, product management, media leadership, and entrepreneurship, Joseph brings a unique perspective to science communication. His expertise allows him to uncover the intersection of technological advancements and market potential, shedding light on how groundbreaking research evolves into transformative products and industries.