69-million-year-old fossil discovery reveals earliest modern bird

A 69-million-year-old bird skull from Antarctica confirms early waterfowl evolution, reshaping our understanding of bird history.

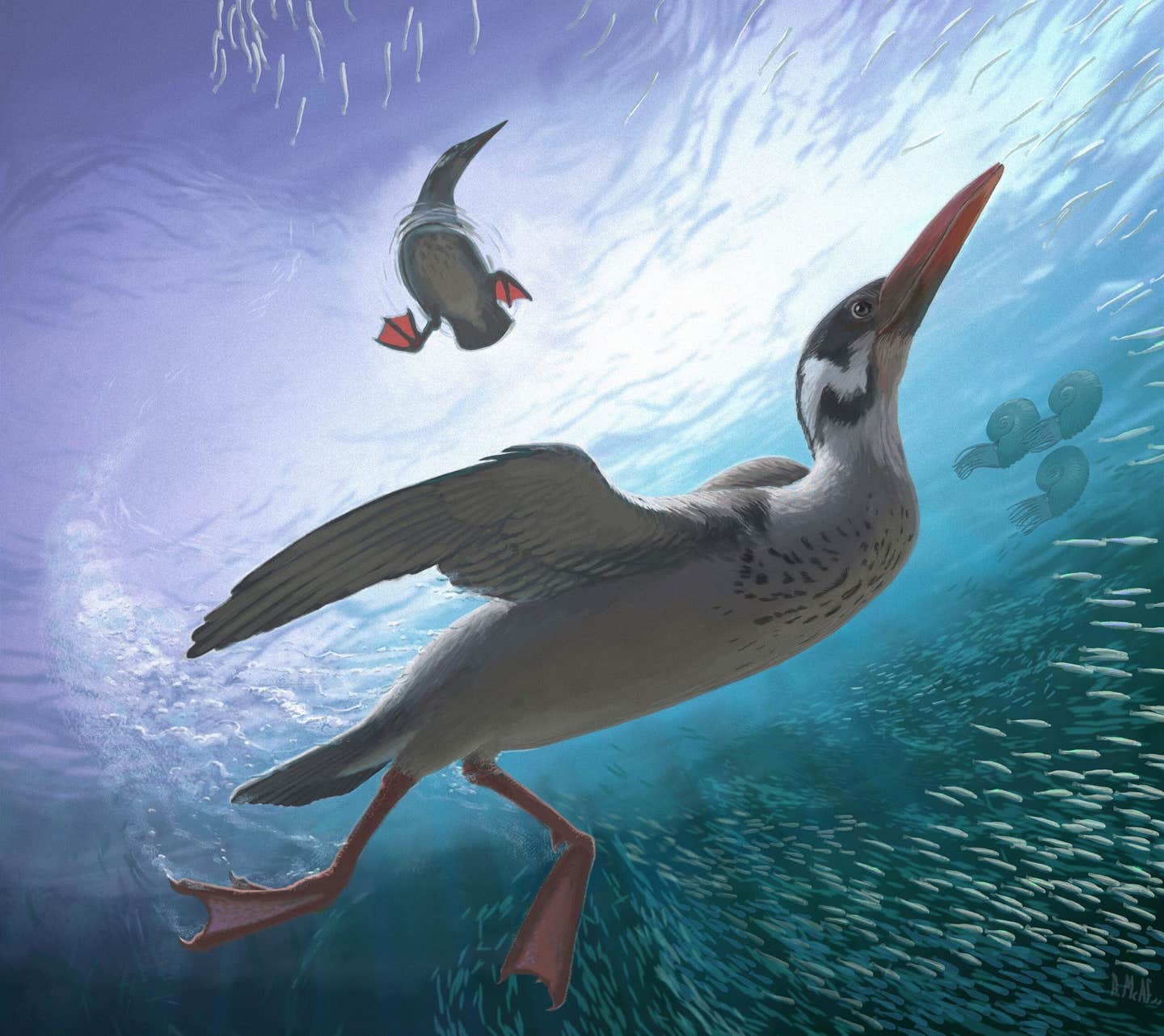

A pair of Vegavis iaai, the earliest known modern bird at 69 million years ago, foraging for fish and other animals in the Late Cretaceous ocean off the coast of the Antarctic Peninsula. (CREDIT: Andrew McAfee (Carnegie Museum of Natural History), 2025)

Sixty-six million years ago, an asteroid impact triggered the extinction of non-avian dinosaurs. Yet, some early birds, including the ancestors of modern waterfowl, survived.

A new discovery from Antarctica provides fresh insight into their evolution. Scientists at Ohio University have unearthed a nearly complete 69-million-year-old bird skull that could resolve long-standing debates about bird ancestry.

The fossil, belonging to Vegavis iaai, was discovered during a 2011 Antarctic expedition. A recent study, led by Dr. Christopher Torres at Ohio University and published in Nature, confirms Vegavis as an early member of modern birds. The fossilized skull offers details on brain shape, beak structure, and feeding adaptations, reinforcing its connection to today’s waterfowl.

A Skull That Changes Everything

Bird fossils from the Mesozoic Era are rare and often fragmentary, making it difficult to trace early bird evolution. Before this discovery, Vegavis was mainly known from postcranial remains, with only partial jaw fragments available. The newly examined skull changes that.

Using high-resolution X-ray micro-computed tomography (µCT), researchers reconstructed the skull in 3D. The results revealed critical avian traits, such as a beak devoid of teeth, a reduced maxillary contribution to the beak margin, and a brain shape similar to modern waterfowl.

“This new fossil is going to help resolve a lot of arguments,” said Dr. Torres. “Chief among them: where is Vegavis perched in the bird tree of life?”

The skull exhibits features unique to modern ducks and geese. Unlike most waterfowl today, its beak and jaw muscles suggest it was a diving predator, similar to loons or grebes. The discovery supports Vegavis as a true member of Anseriformes, a group that includes ducks, geese, and swans.

Related Stories

During the Late Cretaceous, Antarctica was not the frozen wasteland it is today. Fossil evidence suggests a temperate climate with forests and abundant water sources. Scientists speculate that Antarctica’s isolation helped preserve early bird species, shielding them from the catastrophic events that led to mass extinction elsewhere.

“And those few places with any substantial fossil record of Late Cretaceous birds, like Madagascar and Argentina, reveal an aviary of bizarre, now-extinct species with teeth and long bony tails,” noted Dr. Patrick O’Connor of Ohio University. “Something very different seems to have been happening in the far reaches of the Southern Hemisphere.”

This isolated environment may have provided the stability needed for the ancestors of today’s birds to thrive. The fossil evidence supports the idea that modern bird lineages originated in the Southern Hemisphere before expanding globally.

Evolutionary Clues From a 69-Million-Year-Old Brain

The fossilized skull of Vegavis preserves a rare endocast of the brain. The reconstruction shows a large cerebrum with hypertrophy similar to modern birds, meaning its brain had begun developing structures associated with advanced behaviors.

The optic lobes of Vegavis are ventrally deflected, a feature unique to modern birds. This trait suggests improved visual processing, which may have played a role in its survival. The wulst, a structure associated with sensory integration, is broad and comprises around half of the dorsal brain surface.

“Few birds are as likely to start as many arguments among paleontologists as Vegavis,” said Dr. Torres. “This fossil underscores that Antarctica has much to tell us about the earliest stages of modern bird evolution.”

Unlike most modern waterfowl, Vegavis exhibits deep temporal fossae in the skull, a feature found in diving birds like grebes and cormorants. This suggests that Vegavis was an active underwater hunter, pursuing fish rather than filtering food from water like modern ducks.

What This Discovery Means for Bird Evolution

The findings reshape our understanding of how modern birds evolved. Scientists had long debated whether Vegavis belonged to the crown group of birds or was a more primitive species. The new skull provides definitive proof that it was part of the lineage leading to today’s waterfowl.

“This discovery exemplifies the power of scientific research and the crucial role our institution plays in advancing knowledge about Earth's deep history,” said Ohio University President Lori Stewart Gonzalez.

Dr. Torres, now a professor at the University of the Pacific, emphasized that the study is a significant step in understanding bird evolution before the asteroid impact. “Large-scale projects like this one, involving students and postdoctoral researchers, prepare the scientists of tomorrow to collaborate, advance science, and tackle the biggest questions facing our planet,” added Dr. O’Connor.

With Antarctica revealing more secrets from Earth’s past, Vegavis stands as a crucial link in bird evolution. As scientists continue to uncover ancient fossils, this discovery may be just the beginning of rewriting avian history.

Note: Materials provided above by The Brighter Side of News. Content may be edited for style and length.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News' newsletter.

Joseph Shavit

Head Science News Writer | Communicating Innovation & Discovery

Based in Los Angeles, Joseph Shavit is an accomplished science journalist, head science news writer and co-founder at The Brighter Side of News, where he translates cutting-edge discoveries into compelling stories for a broad audience. With a strong background spanning science, business, product management, media leadership, and entrepreneurship, Joseph brings a unique perspective to science communication. His expertise allows him to uncover the intersection of technological advancements and market potential, shedding light on how groundbreaking research evolves into transformative products and industries.