4,000-year-old town found hidden in Saudi Arabian oasis

Archaeologists uncover a 4,000-year-old town in Saudi Arabia, shedding light on slow urbanization in early Arabian societies.

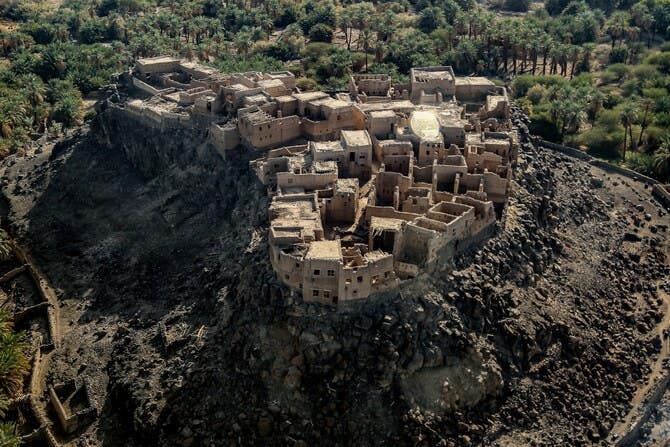

Hidden for millennia, a 4,000-year-old fortified town in Saudi Arabia’s Khaybar Oasis reveals a unique path to urbanization. (CREDIT: Mohammad QASIM / AFP)

In the arid desert of Saudi Arabia, the Khaybar Oasis holds a remarkable discovery: the ruins of an ancient town that tell a story of slow, transformative urbanization. Buried for millennia beneath layers of black basalt rock, this settlement—named al-Natah by researchers—offers a glimpse into the lives of people who transitioned from nomadic herding to organized urban life over 4,000 years ago.

Archaeologists have uncovered the remnants of this once-thriving town, reshaping our understanding of early urbanization on the Arabian Peninsula.

Led by French archaeologist Guillaume Charloux and his team, a French-Saudi collaboration has uncovered this Bronze Age site near the present-day city of Al-'Ula. The team's findings, published recently in the journal PLOS One, reveal that al-Natah likely housed around 500 residents and covered approximately 3.7 acres, or 1.5 hectares. A 14.5-kilometer wall enclosed the town, shielding it from potential threats and marking the boundaries of a unique social structure.

Al-Natah is unlike other cities of the same era, such as those in Egypt or Mesopotamia. Instead of large, bustling centers with well-established infrastructures, this small settlement shows a slower, community-centered form of urbanization. Researchers call this process "slow urbanism," highlighting a gradual shift from pastoral lifestyles to small-scale, organized communities that adapted to life in the desert.

“This type of settlement suggests a unique path to urbanization, one distinct from the bustling cities of Egypt and Mesopotamia,” Charloux noted. He explained that in northwestern Arabia, towns were fortified oases rather than sprawling city-states. While early civilizations in Mesopotamia and Egypt flourished with complex social systems and larger populations, al-Natah developed a different model of urban life suited to its environment.

The discovery at al-Natah builds on earlier archaeological work in the region. Fifteen years ago, researchers found Bronze Age ramparts in Tayma, an oasis north of Khaybar, sparking further studies of settlements across northwestern Arabia. "That first discovery was essential," Charloux said. It encouraged scientists to look deeper into the Arabian oases, revealing an unexpected pattern of development.

Observing al-Natah from above offered initial clues to the town's layout. Satellite images exposed pathways and house foundations, directing archaeologists on where to dig. Excavations revealed sturdy foundations capable of supporting multi-story buildings—a sign of advanced planning and construction techniques. Although no examples of writing have been found at the site, Charloux suggests that the al-Natah people likely grew crops nearby, relying on agriculture as well as animal husbandry.

Related Stories

Evidence from pottery fragments supports the idea of a structured community with clear social organization. Researchers found pieces of simple but attractive ceramics, which they believe point to a relatively egalitarian society. According to Charloux, these ceramics, along with grinding stones and other artifacts, indicate that people lived in close-knit communities focused on sustenance and survival rather than vast wealth or elaborate displays of power.

A large necropolis found in the western part of al-Natah’s central district hints at complex burial customs. This cemetery contains distinctive “stepped tower tombs” along with metal artifacts, such as axes and daggers, which suggest that the people of al-Natah had access to metalworking technologies. Agate and other stones found in the tombs indicate trade networks that likely extended beyond the oasis.

One notable feature of al-Natah is the fortified wall surrounding it. The wall, stretching approximately 14.5 kilometers (or nine miles), would have served as a powerful defense against raids from nomadic groups in the region. “The sheer scale of these ramparts suggests that al-Natah was home to a powerful local authority,” Charloux explained. This level of fortification points to an organized society, capable of both constructing and maintaining substantial defenses.

While other Bronze Age civilizations in the Levant, Mesopotamia, and Egypt were expanding into complex city-states, settlements like al-Natah evolved more slowly. The Khaybar Oasis, despite its smaller population and simpler architecture, illustrates how early societies on the Arabian Peninsula adapted to their harsh surroundings. This adaptation involved balancing between nomadic traditions and new forms of urban life.

The researchers hypothesize that these early fortified oases may have facilitated interactions across the desert, laying the foundation for future trade routes. Charloux suggests that such exchanges could have even contributed to the beginnings of the “incense route”—a trade network that would later transport goods like frankincense, myrrh, and spices from southern Arabia to the Mediterranean.

Despite its size, al-Natah’s influence and its inhabitants' way of life offer valuable insights. The slow urbanization seen in this town provides a unique perspective on societal development, showing how urbanization did not always follow the rapid, large-scale patterns seen in other ancient civilizations. Charloux noted, “This gradual process allowed for a distinctive model of urban life, one that was modest, slower, and specific to northwestern Arabia.”

The reasons for al-Natah’s eventual abandonment remain unknown. Researchers estimate that people left the town between 1500 and 1300 B.C., around a thousand years after it was first established. Charloux acknowledged the mystery, stating, “We have very few clues about the last phase of occupation.” Environmental changes, resource depletion, or shifts in trade routes could have played a role, but further evidence is needed to clarify the cause.

Scholars outside the project have praised the findings at al-Natah for adding depth to our understanding of the region’s history. Juan Manuel Tebes, director of the Center of Studies of Ancient Near Eastern History at the Catholic University of Argentina, highlighted the research’s importance.

“The Khaybar project significantly expands our knowledge of urbanization in northwestern Arabia,” Tebes remarked. He noted that previous archaeological efforts in Tayma and Qurayyah have provided essential information, helping historians piece together a timeline of the region’s social and cultural evolution.

Robert Andrew Carter, a senior archaeology academic at Qatar Museums, also commended Charloux and his team. Carter, who specializes in fieldwork in the Hejaz region, stated that this study “greatly enriches our understanding of the Bronze Age in western Saudi Arabia.” He emphasized that these findings contribute to a broader theoretical framework for early Arabian urbanization, illustrating a path distinct from those taken by Egypt and Mesopotamia.

Today, the Khaybar Oasis stands as a testament to the ingenuity of early civilizations that managed to thrive in challenging environments. Al-Natah may be modest compared to the great cities of its time, but it reveals a unique story of resilience, adaptation, and gradual societal transformation.

Archaeologists continue to study this site, hoping to uncover more details about the daily lives, cultural practices, and eventual fate of the people who once called it home.

Note: Materials provided above by The Brighter Side of News. Content may be edited for style and length.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News' newsletter.

Rebecca Shavit

Science & Technology Journalist | Innovation Storyteller

Based in Los Angeles, Rebecca Shavit is a dedicated science and technology journalist who writes for The Brighter Side of News, an online publication committed to highlighting positive and transformative stories from around the world. With a passion for uncovering groundbreaking discoveries and innovations, she brings to light the scientific advancements shaping a better future. Her reporting spans a wide range of topics, from cutting-edge medical breakthroughs and artificial intelligence to green technology and space exploration. With a keen ability to translate complex concepts into engaging and accessible stories, she makes science and innovation relatable to a broad audience.