2,500-year-old lost city discovered sunken off the coast of Egypt

Sunken city of Thonis-Heracleion, Egypt’s largest port before Alexandria, reveals its lost history through ongoing underwater excavations.

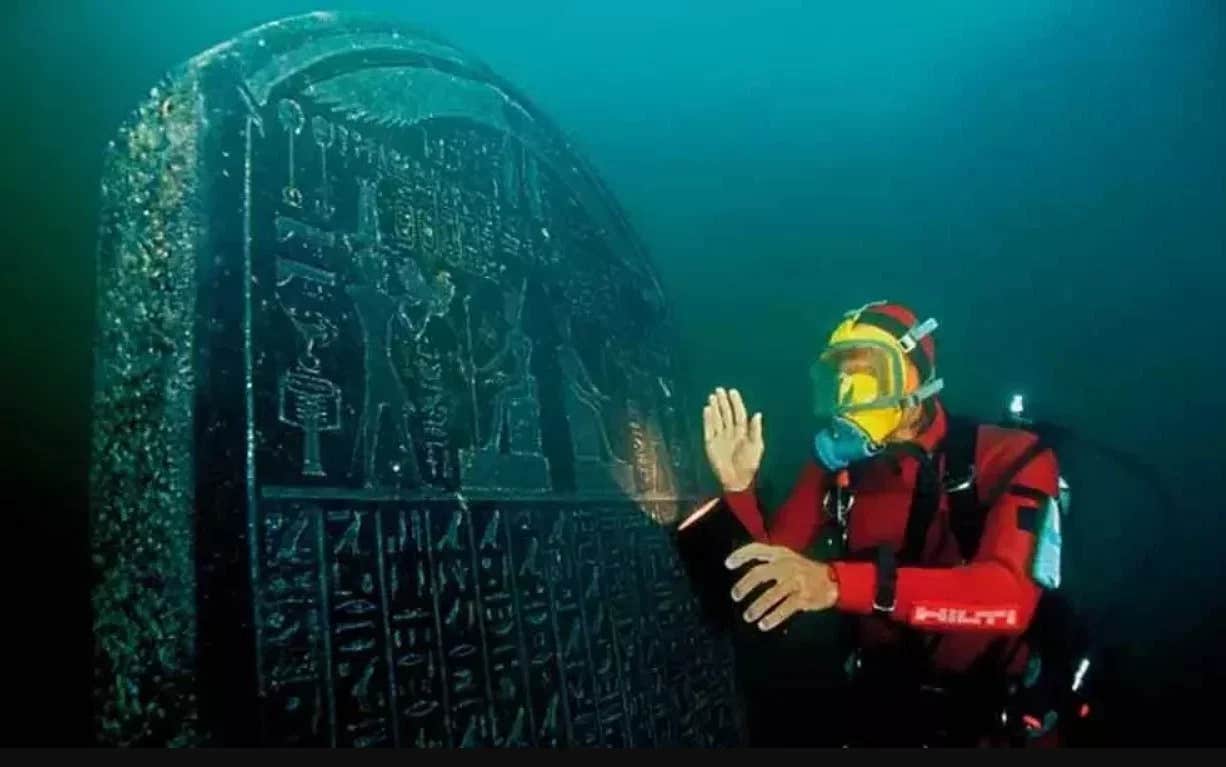

Franck Goddio examines the stele of Thonis-Heracleion erected on site under water in the city of Thonis-Heracleion, Abukir Bay. The intact stele (1.99 m) is inscribed with the decree of Saϊs. It was commissioned by Nectanebos I (380-362 BC). (CREDIT: Franck Goddio/Hilti Foundation, photo: Christoph Gerigk)

Thonis-Heracleion was once a bustling city at the mouth of the River Nile, serving as Egypt’s primary port for international trade before the rise of Alexandria in 331 BCE. This city, a fusion of myth and reality, played a vital role in ancient Egyptian civilization, hosting a grand temple dedicated to Amun, which had significance in the country’s dynastic rites.

Founded around the 8th century BCE, Thonis-Heracleion thrived for centuries, surviving natural disasters until it finally sank into the Mediterranean in the 8th century AD. Lost to time, it vanished from all records except for the accounts of historians like Herodotus, who described the city’s temple as the place where the Greek hero Herakles first set foot in Egypt.

Strabo, another ancient geographer, placed it at the Canopic mouth of the Nile. Despite these historical mentions, no physical trace of the city was found until the turn of the 21st century.

In 2000, Franck Goddio and his team from the European Institute for Underwater Archaeology (IEASM) made a groundbreaking discovery. After years of research beginning in 1996, they finally located the sunken city of Thonis-Heracleion six kilometers off Egypt’s coast, submerged under 10 meters of water in Aboukir Bay.

This discovery not only brought the lost city back into the light, but it also solved an archaeological puzzle—Thonis and Heracleion were the same city, known by different names to the Egyptians and Greeks. What Goddio and his team uncovered was a vast civilization frozen in time.

From grand temples and colossal statues to daily life artifacts like coins and ceramics, the relics recovered tell the story of a city that flourished between the 6th and 4th centuries BCE. Its extensive harbors made it a crucial hub of trade, drawing merchants from across the Mediterranean.

Archaeologists found over 700 anchors and 79 shipwrecks, vivid evidence of the city’s bustling maritime activity. A network of canals intertwined with the city’s layout, giving it a lake-like appearance with temples and homes scattered across the islands.

Related Stories

Thonis-Heracleion also served as a religious center, where the Mysteries of Osiris were celebrated annually, symbolizing the god’s rebirth. Ceremonies took place along the canals, with Osiris being carried in a ceremonial boat from the temple of Amun-Gereb to his shrine in Canopus. These rituals were central to the religious and cultural identity of the city.

One of the more recent and significant discoveries came in 2021 when an Egyptian-French underwater team uncovered the remains of a military vessel beneath the ancient city. The ship, built in the classical tradition with Egyptian shipbuilding techniques, sank in the 2nd century BCE while loading massive stones from the temple of Amun.

This ship, around 25 meters long, was a rowing vessel equipped with a large sail. Its flat bottom and keel made it ideal for navigating the Nile and the surrounding Delta.

Ayman Ashmawy from the Egyptian Ministry of Antiquities described the discovery as a rare find, noting that only a handful of such ships from this period have ever been recovered. The ship, buried under five meters of clay and temple debris, was preserved by the very blocks it had been transporting, which settled over the wreck during a cataclysmic event.

Further excavations revealed a large funerary complex that likely belonged to Greek merchants who had settled in Thonis-Heracleion during the late Pharaonic dynasties.

These merchants, who had constructed their own sanctuaries near the grand Egyptian temple, were integral to the city's economy, controlling access to Egypt at the Canopic branch of the Nile. Their presence underscores the multicultural nature of the city, where Egyptians and Greeks lived side by side, sharing religious and commercial spaces.

Thonis-Heracleion’s story does not end with these discoveries. Archaeologists believe that only 5% of the city has been excavated so far, leaving much of its history still submerged beneath the sea. Mostafa Waziri, Secretary-General of the Supreme Council of Antiquities, emphasized the significance of these finds, noting that the city was once Egypt’s largest port before Alexandria was established.

The city’s downfall came through a series of earthquakes and tidal waves that liquefied the land, causing it and the neighboring city of Canopus to sink. Rediscovered in 1999 and 2001, respectively, these two cities continue to provide invaluable insights into ancient Egyptian and Greek interactions.

The underwater exploration of Thonis-Heracleion is far from over. As technology advances, new methods will likely reveal more of the city’s secrets. Franck Goddio believes the city still holds untold treasures, waiting to be unearthed.

The importance of these findings stretches beyond just understanding Thonis-Heracleion; it illuminates a vital chapter in the history of Mediterranean trade and cultural exchange. The city, once lost beneath the sea, now tells its story through the artifacts and ruins brought to the surface.

Note: Materials provided above by The Brighter Side of News. Content may be edited for style and length.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News' newsletter.

Rebecca Shavit

Science & Technology Journalist | Innovation Storyteller

Based in Los Angeles, Rebecca Shavit is a dedicated science and technology journalist who writes for The Brighter Side of News, an online publication committed to highlighting positive and transformative stories from around the world. With a passion for uncovering groundbreaking discoveries and innovations, she brings to light the scientific advancements shaping a better future. Her reporting spans a wide range of topics, from cutting-edge medical breakthroughs and artificial intelligence to green technology and space exploration. With a keen ability to translate complex concepts into engaging and accessible stories, she makes science and innovation relatable to a broad audience.