125 million-year-old giant venomous scorpion fossil unearthed in China

Scientists uncover a 125-million-year-old scorpion fossil in China, revealing its role in an ancient food web.

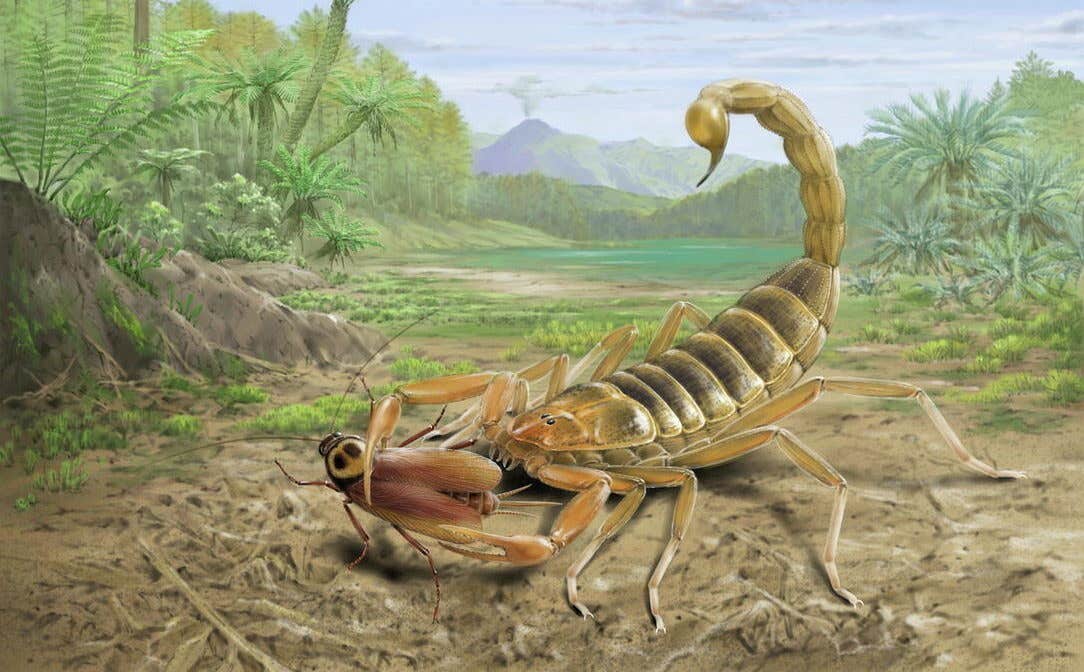

A giant scorpion fossil, Jeholia longchengi, has been discovered in China. (CREDIT: Science Bulletin)

A newly discovered scorpion fossil is rewriting the story of ancient ecosystems. This rare find, named Jeholia longchengi, lived 125 million years ago and belonged to the Early Cretaceous Jehol Biota of northeastern China.

Measuring 10 centimeters in length, it was a giant among its kind, standing out as the largest known scorpion fossil from the Mesozoic era. The discovery sheds new light on the food web of this prehistoric world, where scorpions played a much larger role than previously understood.

A Rare and Unusual Find

Scorpions have walked the Earth for over 400 million years, yet their fossils remain scarce. Unlike insects trapped in amber, these arachnids lived in environments where fossilization was unlikely.

Most known Mesozoic scorpion fossils come from mid-Cretaceous Burmese amber, while compression fossils are rare. The newly identified Jeholia longchengi is the first Mesozoic scorpion fossil ever found in China, and only the fourth terrestrial scorpion fossil unearthed in the country.

This fossil, housed at the Fossil Valley Museum in Chaoyang, China, was preserved in dark grey mudstones from the Yixian Formation in Inner Mongolia.

Researchers carefully examined it using advanced imaging techniques, including high-resolution macro photography and microscopic analysis, to document its features. The team measured key anatomical structures, reconstructing its ecological role within the Jehol Biota’s food web.

A Fierce Predator in a Prehistoric World

Unlike many of its ancient relatives, J. longchengi had long, slender legs, a pentagonal body, and an elongated venomous stinger. These traits suggest it was an agile hunter, preying on insects, spiders, and even small vertebrates. Researchers believe it occupied a mid-level position in the food chain, serving as both a predator and prey.

Related Stories

“If placed in today’s environment, it might become a natural predator of many small animals, and could even hunt the young of small vertebrates,” said Diying Huang, a researcher at the Nanjing Institute of Geology and Palaeontology.

Despite its formidable hunting abilities, J. longchengi likely fell prey to larger creatures. Early birds, mammals, and even small dinosaurs may have targeted these scorpions as part of their diet. The Jehol Biota, a well-known fossil assemblage, was home to feathered dinosaurs, early birds, mammals, and insects, creating a complex food web where J. longchengi played a key role.

A Window Into Prehistoric Ecosystems

Understanding the role of J. longchengi in its environment helps researchers reconstruct ancient ecosystems. Scientists analyzed its place in the Jehol Biota’s food web by studying the diets of related species and examining fossilized gut contents from other Jehol fossils. They also calculated Betweenness Centrality, a metric that reveals how essential a species was in mediating interactions between predators and prey.

High Betweenness Centrality values suggest that J. longchengi was an integral part of its ecosystem, linking various species within the food web. This analysis strengthens the idea that scorpions were more than just minor predators—they were essential players in the balance of ancient biodiversity.

Expanding the Fossil Record

Before this discovery, only three fossilized scorpions had been found in China, dating to the Miocene, Devonian, and Permian periods. The addition of J. longchengi from the Early Cretaceous fills an important gap in the fossil record. Its discovery also highlights the value of the Jehol Biota, a site that continues to yield exceptional fossils of prehistoric life.

“This is the first Mesozoic scorpion from China, and its discovery gives us a fresh perspective on the evolution of these ancient predators,” Huang noted.

The fossil’s remarkable preservation allows scientists to compare its anatomy to modern scorpions, offering insights into their evolutionary history. Features such as rounded spiracles, used for breathing, suggest links to modern Asian scorpion families. However, its elongated limbs and unique body shape set it apart from today’s species.

Despite these insights, many questions remain. The fossil lacks well-preserved mouthparts, making it difficult to determine its exact diet. Future discoveries may provide more evidence to clarify its role in the ecosystem.

The findings were published in the journal Science Bulletin, marking a significant contribution to the study of prehistoric arthropods. As researchers continue to uncover new fossils, each discovery adds another piece to the puzzle of Earth’s ancient past.

Note: Materials provided above by The Brighter Side of News. Content may be edited for style and length.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News' newsletter.

Joseph Shavit

Head Science News Writer | Communicating Innovation & Discovery

Based in Los Angeles, Joseph Shavit is an accomplished science journalist, head science news writer and co-founder at The Brighter Side of News, where he translates cutting-edge discoveries into compelling stories for a broad audience. With a strong background spanning science, business, product management, media leadership, and entrepreneurship, Joseph brings a unique perspective to science communication. His expertise allows him to uncover the intersection of technological advancements and market potential, shedding light on how groundbreaking research evolves into transformative products and industries.