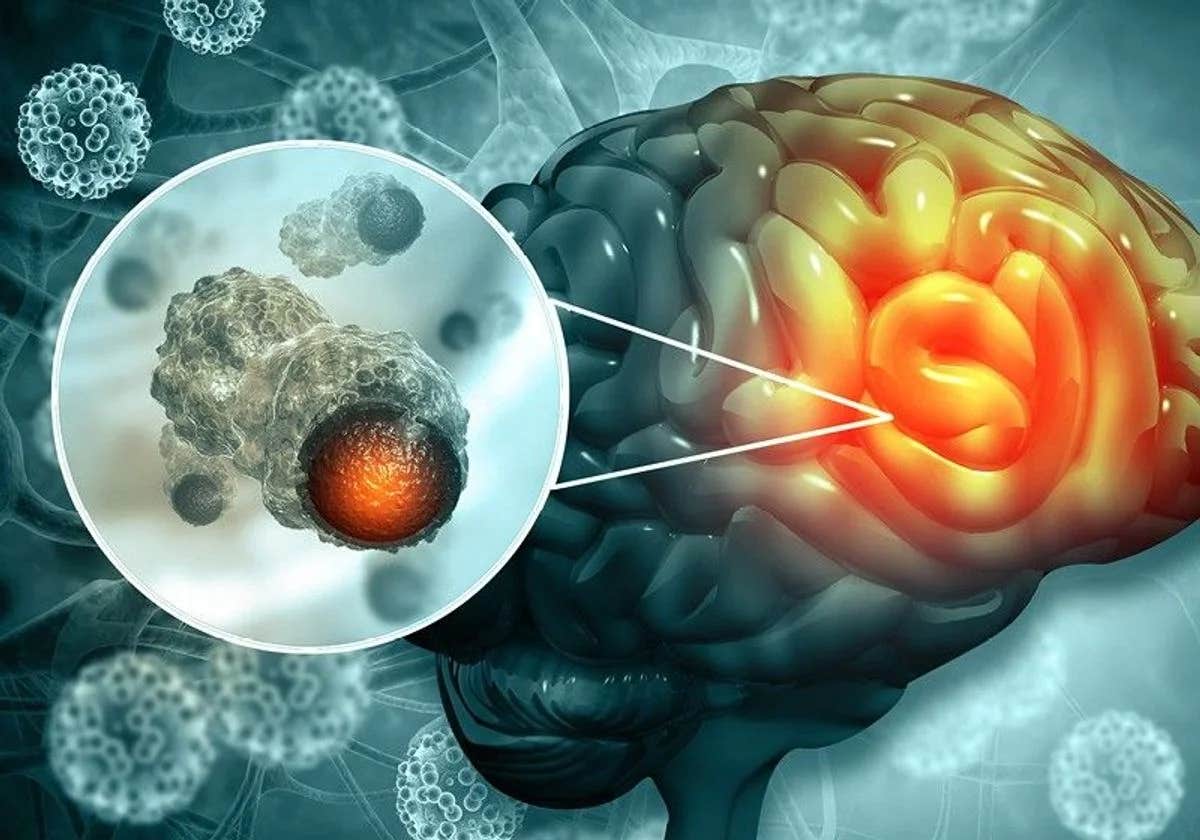

Groundbreaking cancer vaccine found to both kill and prevent brain cancer

Scientists are transforming cancer cells into anti-cancer agents, aiming for a groundbreaking new cancer treatment approach.

Dual-action cell therapy engineered to eliminate established tumors and train the immune system to eradicate primary tumor and prevent cancer’s recurrence. (CREDIT: Creative Commons)

In an audacious bid to rewrite the narrative of cancer treatment, scientists are converging on an ingenious approach: morphing cancer cells into potent anti-cancer soldiers. Spearheading this revolutionary endeavor is Dr. Khalid Shah, MS, PhD, and his stellar team at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, under the aegis of the Mass General Brigham healthcare system.

According to their research published in the esteemed journal, Science Translational Medicine, this cell therapy not only eliminates established tumors but also kickstarts long-term immunity, effectively educating the immune system to thwart any potential resurgence of the disease.

Dr. Khalid Shah, who helms the Center for Stem Cell and Translational Immunotherapy (CSTI) and is also the vice chair of research in the Department of Neurosurgery at the Brigham, elucidates, “Our team has pursued a simple idea: to take cancer cells and transform them into cancer killers and vaccines.”

As a faculty member at both Harvard Medical School and Harvard Stem Cell Institute (HSCI), Shah’s pioneering stance is backed by an enviable academic heft.

Harnessing the ever-evolving domain of gene engineering, Shah's team is not merely content with destroying cancer. They aim to “repurpose cancer cells to develop a therapeutic that kills tumor cells and stimulates the immune system to both destroy primary tumors and prevent cancer.”

The quest for cancer vaccines has kept many a lab buzzing. However, what sets Shah and his team apart is their unique methodology. While traditional research focuses on inactivated tumor cells, Shah’s methodology zeroes in on living tumor cells, which, in an almost poetic nod to homing pigeons, journey across vast expanses of the brain to reunite with their kin.

Leveraging this innate trait, the team adeptly modified these living tumor cells. Utilizing the advanced gene editing tool, CRISPR-Cas9, they have endowed these cells with the capability to unleash a potent tumor cell-killing agent. Simultaneously, these transformed cells were crafted to exhibit markers, making them easily identifiable by the immune system. This facilitates not only an immediate defensive response but also primes the immune system for sustained anti-tumor actions.

Related Stories

In the ensuing experiments, the team tested these repurposed, CRISPR-enhanced, and meticulously reverse-engineered therapeutic tumor cells (ThTC). The subjects? A variety of mice strains, some even bearing bone marrow, liver, and thymus cells originating from humans – an attempt to mirror the human immune microenvironment.

Dr. Shah and his team didn’t just stop there. Incorporating a commendable foresight, they integrated a two-tiered safety switch within the cancer cell. This switch, upon activation, can obliterate ThTCs, if deemed necessary. Preliminary results? This dual-action cell therapy emerged as safe, adaptable, and effective, charting a course towards potential therapeutic applications.

Importantly, the choice of using human cells in their mouse model was strategic. As Shah explains, “Even when it is highly technical, we never lose sight of the patient. Our goal is to take an innovative but translatable approach so that we can develop a therapeutic, cancer-killing vaccine that ultimately will have a lasting impact in medicine.”

Shah and his team advocate for this therapeutic model's applicability beyond just glioblastoma, suggesting its relevance for a wider spectrum of solid tumors. Their clarion call? Further exploration into this promising realm.

In an era where the mere mention of cancer sends shivers down spines, this novel approach, with its dual-pronged assault on cancer cells, offers a glimmer of hope. The path may be winding, but with relentless researchers like Dr. Khalid Shah at the helm, the journey seems promising.

How common are brain tumors, and are they dangerous?

In the United States, brain and nervous system tumors affect about 30 adults out of 100,000. Brain tumors are dangerous because they can put pressure on healthy parts of the brain or spread into those areas. Some brain tumors can also be cancerous or become cancerous. They can cause problems if they block the flow of fluid around the brain, which can lead to an increase in pressure inside the skull. Some types of tumors can spread through the spinal fluid to distant areas of the brain or the spine.

Brain Tumor Symptoms

According to Johns Hopkins Medicine, different parts of the brain control different functions, so brain tumor symptoms will vary depending on the tumor’s location.

For example, a brain tumor located in the cerebellum at the back of the head may cause trouble with movement, walking, balance and coordination. If the tumor affects the optic pathway, which is responsible for sight, vision changes may occur.

The tumor’s size and how fast it’s growing also affect which symptoms a person will experience.

In general, the most common symptoms of a brain tumor may include:

- Headaches

- Seizures or convulsions

- Difficulty thinking, speaking or finding words

- Personality or behavior changes

- Weakness, numbness or paralysis in one part or one side of the body

- Loss of balance, dizziness or unsteadiness

- Loss of hearing

- Vision changes

- Confusion and disorientation

- Memory loss

Brain Tumor Causes and Risk Factors

Doctors don’t know why some cells begin to form into tumor cells. It may have something to do with a person’s genes or his or her environment, or both. Some potential brain tumor causes and risk factors may include:

- Cancers that spread from other parts of the body

- Certain genetic conditions that predispose a person to overproduction of certain cells

- Exposure to some forms of radiation

Are brain tumors hereditary?

Genetics are to blame for a small number (fewer than 5%) of brain tumors. Some inherited conditions put individuals at greater risk of developing tumors, including:

- Neurofibromatosis

- Von Hippel-Lindau disease

- Li-Fraumeni syndrome

- Familial adenomatous polyposis

- Lynch syndrome

- Basal cell nevus syndrome (Gorlin syndrome)

- Tuberous sclerosis

- Cowden syndrome

Note: Materials provided above by The Brighter Side of News. Content may be edited for style and length.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News' newsletter.

Joseph Shavit

Head Science News Writer | Communicating Innovation & Discovery

Based in Los Angeles, Joseph Shavit is an accomplished science journalist, head science news writer and co-founder at The Brighter Side of News, where he translates cutting-edge discoveries into compelling stories for a broad audience. With a strong background spanning science, business, product management, media leadership, and entrepreneurship, Joseph brings a unique perspective to science communication. His expertise allows him to uncover the intersection of technological advancements and market potential, shedding light on how groundbreaking research evolves into transformative products and industries.