Breakthrough study finds that Earth has six continents not seven

From an early age, most of us are taught to recognize seven continents: Africa, Antarctica, Asia, Oceania, Europe, North America, and South America.

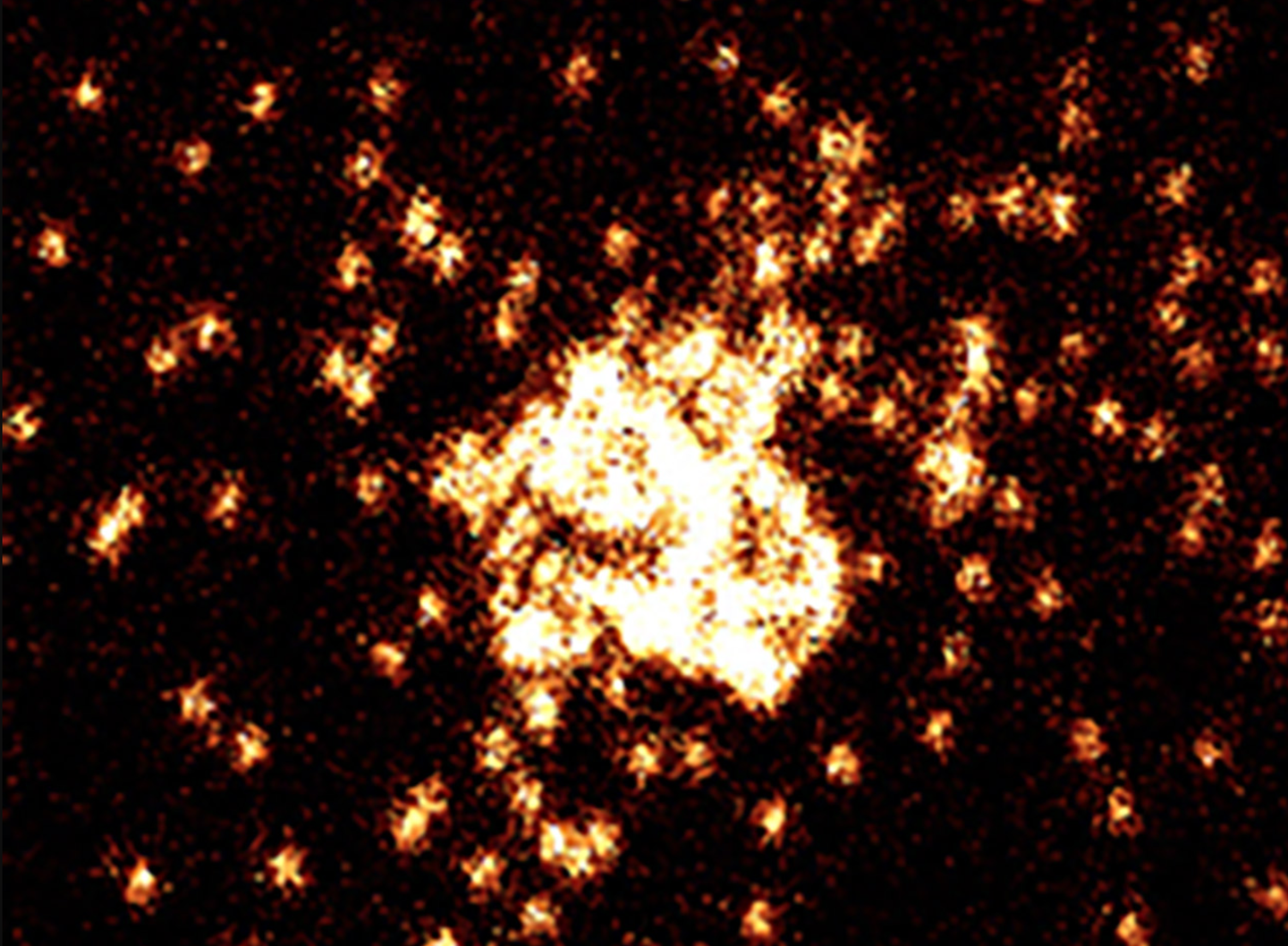

The study focuses on the volcanic island of Iceland. (CREDIT: skynesher/Getty Images)

Forget what you learned in school—Earth might not have seven continents after all.

From an early age, most of us are taught to recognize seven continents: Africa, Antarctica, Asia, Oceania, Europe, North America, and South America. But groundbreaking research published in the journal Gondwana Research challenges that long-held notion.

The study, led by Dr. Jordan Phethean from the University of Derby, argues that the traditional division of continents might not be as clear-cut as we think. According to the findings, North America and Europe—separated by the Atlantic Ocean—may still be geologically linked.

"The North American and Eurasian tectonic plates have not yet actually broken apart, as is traditionally thought to have happened 52 million years ago," Dr. Phethean explained. Instead, these plates are still stretching and gradually pulling apart, suggesting that they remain part of a single, evolving landmass rather than two distinct continents.

Central to this research is Iceland, a volcanic island long thought to have formed about 60 million years ago at the mid-Atlantic ridge—a tectonic boundary between the North American and Eurasian plates. Traditionally, scientists believed the ridge triggered a hot mantle plume, eventually creating the island.

However, the new study proposes a more nuanced view, emphasizing how this geological process supports the idea that North America and Europe have not yet fully separated.

This reinterpretation of Earth's geological history calls into question the definition of continents and could reshape how we understand our planet’s evolution.

Related Stories:

However, by carefully analyzing tectonic movements across Africa, Phethean and his colleagues have challenged this theory and put forward a radical new idea. They argue that Iceland, along with the Greenland Iceland Faroes Ridge (GIFR), contains geological fragments from both European and North American tectonic plates.

This suggests that these regions are not isolated landforms as previously thought but interconnected pieces of a larger continental structure. The scientists have even coined the term “Rifted Oceanic Magmatic Plateau” (ROMP) to describe this new geological feature, which could fundamentally alter our perception of the formation and separation of Earth’s continents.

Phethean describes the discovery as the Earth Science equivalent of finding the Lost City of Atlantis because his team uncovered “fragments of lost continent submerged beneath the sea and kilometers of thin lava flows.”

Furthermore, the researchers have found striking similarities between Iceland and Africa’s volcanic Afar region. If their study proves accurate, this would mean that the European and North American continents are still in the process of breaking apart and are, therefore, still linked. Phethean acknowledges that his team’s findings will raise some eyebrows but insists they are grounded in meticulous research.

“It is controversial to suggest that the GIFR contains a large amount of continental crust within it and that the European and North American tectonic plates have perhaps not yet officially broken up,” he admitted, while stressing that his work supports these hypotheses.

Nevertheless, the research is still in its conceptual phase, and the team aims to conduct further tests on Iceland’s volcanic rocks to obtain more concrete evidence of an ancient continental crust. They are also employing computer simulations and plate tectonic modeling to better understand how the ROMP is formed.

This research follows Phethean’s earlier discovery of a hidden “proto-microcontinent” nestled between Canada and Greenland. This primitive landmass, about the size of England, sits below the Davis Strait, just off Baffin Island.

Phethean noted that “rifting and microcontinent formation are ongoing phenomena” that help scientists better understand the behavior of continents and plate tectonics. Such knowledge can help experts predict how our planet might look in the distant future and locate where useful resources may be found.

Our understanding of Earth's continents might need an update based on these groundbreaking findings. The research suggests that the interconnected nature of North America and Europe challenges long-held geological beliefs and opens new avenues for studying Earth's dynamic processes.

As scientists continue to investigate, the very map of the world we thought we knew may change.

Note: Materials provided above by The Brighter Side of News. Content may be edited for style and length.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News' newsletter.

Joseph Shavit

Head Science News Writer | Communicating Innovation & Discovery

Based in Los Angeles, Joseph Shavit is an accomplished science journalist, head science news writer and co-founder at The Brighter Side of News, where he translates cutting-edge discoveries into compelling stories for a broad audience. With a strong background spanning science, business, product management, media leadership, and entrepreneurship, Joseph brings a unique perspective to science communication. His expertise allows him to uncover the intersection of technological advancements and market potential, shedding light on how groundbreaking research evolves into transformative products and industries.