Archeologists discover how Egypt’s first pyramid may have been built

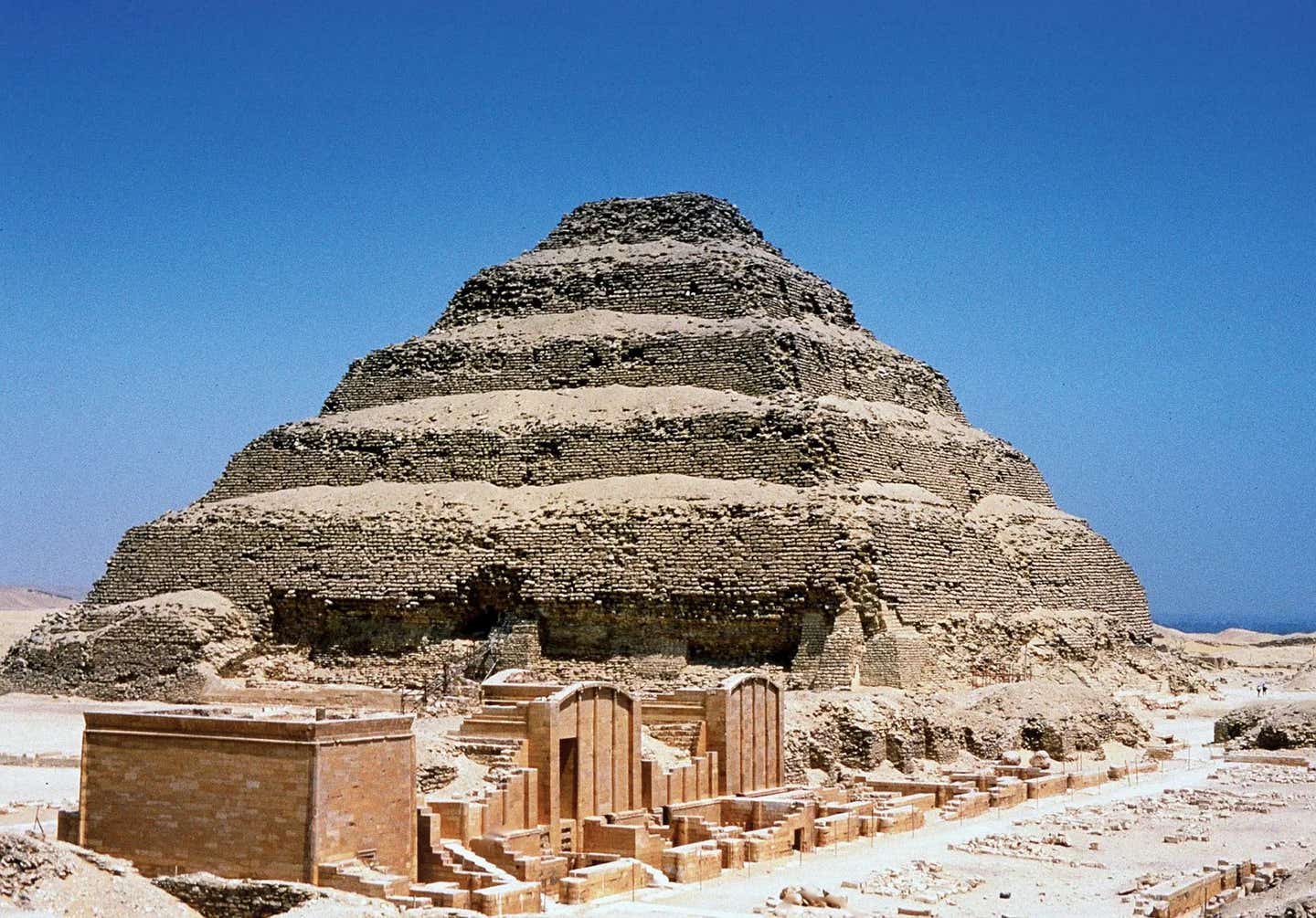

Ancient architects might have designed a hydraulic system to hoist stone blocks, used to assemble the six-tiered, roughly 62-meter-tall pyramid of King Djoser.

Ancient architects might have designed a hydraulic system to hoist stone blocks, used to assemble the six-tiered, roughly 62-meter-tall pyramid of King Djoser. (CREDIT: Creative Commons)

Builders of Egypt’s oldest known pyramid, the nearly 4,700-year-old Step Pyramid of Djoser at Saqqara, may have used waterpower to help construct this monumental structure.

Ancient architects might have designed a hydraulic system to hoist stone blocks, used to assemble the six-tiered, roughly 62-meter-tall pyramid of King Djoser.

This proposal, detailed by scientists in PLOS ONE, suggests that controlled water flows in and out of a large shaft inside the pyramid lifted and lowered a platform carrying building stones to higher levels. Xavier Landreau, from the Paris research institute Paleotechnic, and his colleagues support this theory.

Although the idea is intriguing, some researchers are skeptical. They aren't fully convinced that pyramid builders used such a device. Landreau, with expertise in materials science and plasma physics, founded Paleotechnic to explore ancient technologies.

There is no universally accepted method for how ancient Egyptians built pyramids from millions of massive stone blocks, each weighing up to around 2,500 kilograms. Suggested techniques include ramps, cranes, rope-and-pulley devices, and rolling wooden rods attached to stones.

Earlier this year, another team of researchers identified a now-dry Nile tributary that borders a chain of 31 pyramids, including Djoser's. This discovery suggests that vessels carrying workers and materials could have traveled along this branch to sites where pyramids were constructed between around 4,700 and 3,700 years ago.

Landreau believes water played an even more crucial role in constructing Egypt's first pyramid. He argues that Djoser’s pyramid designers expertly managed water flow, a knowledge field now known as hydraulics.

Related Stories

How the Hydraulic System May Have Worked

The proposed hydraulic system stems from a computer model incorporating data on the pyramid’s surviving internal features and a network of underground tunnels at the site. The team also used high-resolution satellite images to model ancient rainfall and runoff levels.

In this model, a walled enclosure several hundred meters from the pyramid captured floodwater that flowed through desert channels during periodic heavy rains. Known as Gisr el-Mudir, this structure directed water to a basin west of Djoser’s burial grounds. Intense rains could have temporarily turned the basin into a lake, draining into a section of a limestone trench encircling the burial complex.

Researchers have previously suggested that this trench, called the Dry Moat, served as a quarry or a model of the pharaoh’s path to the afterlife.

The team’s model proposes that water from the Dry Moat entered two large, excavated shafts, including one inside the pyramid. Granite chambers at the bottom of these shafts contained stone plugs that, when removed, allowed water to rush in. This setup formed the basis of a hydraulic lift.

In this hypothetical design, a massive wooden float rested above the granite chamber. The float was attached to long ropes passing over pulleys at the top of the shaft, looping around to connect to a lift platform. As water filled or drained from the shaft, the float and lift platform would counterbalance each other.

Access points for workers hauling building stones to the lift platform were either at ground level or through a tunnel located several meters above ground. As water filled the shaft, the float rose, lowering the platform. Once stones were placed on the platform, the shaft was drained. The descending float then pulled the platform and its cargo up to new construction levels.

Skepticism Surrounding the Hydraulic Theory

University of Toronto archaeologist Oren Siegel argues that Gisr el-Mudir could not have held enough water from occasional rains to sustain Landreau’s hydraulic system. Siegel suggests Gisr el-Mudir might represent an early experiment in building stone enclosures that later surrounded pharaohs’ burial sites.

Egyptologist Kamil Kuraszkiewicz adds another complication: the proposed lake isn't mentioned in any ancient writings and may never have existed. Moreover, Djoser’s pyramid stones, averaging about 300 kilograms each, were smaller and easier for workers to transport than those used in later pyramids.

"To build the hydraulic device proposed in the new model, much more effort would be needed than to move the stone blocks using just manpower," says Kuraszkiewicz, of the University of Warsaw.

Landreau calls for further research at Djoser’s pyramid. It's unclear how high the partially excavated north shaft extends, limiting the ability to model the hydraulic lift system accurately. However, he predicts that stonework on the shaft sides would have supported a structure rising beyond its known length of about four meters aboveground. Further exploration and excavation might shed more light on this ancient engineering marvel.

Note: Materials provided above by The Brighter Side of News. Content may be edited for style and length.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News' newsletter.