Uranus’s extreme radiation belts linked to ancient solar wind event

New research suggests Uranus’s intense radiation belts may have formed during a powerful solar wind storm, not from unknown physics.

Edited By: Joshua Shavit

Edited By: Joshua Shavit

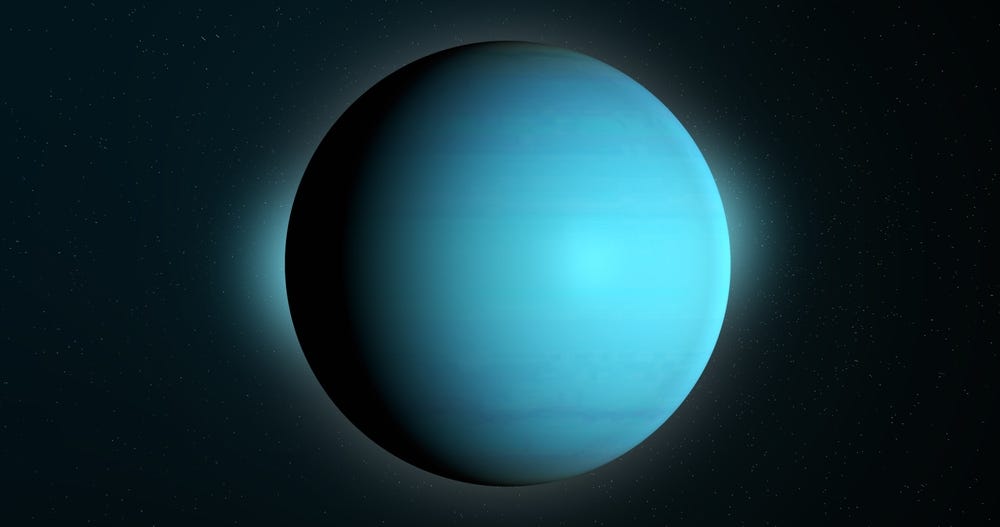

Scientists say a solar wind storm may explain Uranus’s powerful radiation belts seen by Voyager 2. (CREDIT: Shutterstock)

Far from the Sun, Uranus sits tipped on its side, carrying a magnetic system unlike any other planet’s. Its equator tilts about 97.7 degrees relative to its orbit, so the planet spends long stretches with its spin axis aimed almost directly at the Sun. At other times, that axis lies nearly sideways. These extreme seasons are expected to reshape how the solar wind pushes against the planet’s magnetic field.

Uranus’s magnetism adds another layer of complexity. The main dipole part of its magnetic field tilts about 60 degrees away from the rotation axis and appears offset from the planet’s center. Scientists interpret this shift as evidence that higher-order magnetic components play a strong role. The result is a tangled magnetic geometry that differs sharply from Earth’s more orderly field.

This unusual setup controls how charged particles move, gain energy, and become trapped. It shapes the radiation belts, regions of high-energy electrons and ions that encircle magnetized planets. For decades, however, scientists had only one brief look at Uranus’s belts, captured during a single flyby.

A Surprising Snapshot from Voyager 2

Voyager 2 passed Uranus in 1986 and remains the only spacecraft to do so. By chance, the planet’s rotation axis then lay close to the line between Uranus and the Sun, an uncommon alignment. During the encounter, the spacecraft detected radiation belts within about four Uranus radii of the planet, where one radius equals 25,559 kilometers.

The findings puzzled researchers. "The ion belt appeared weaker than we expected, while the electron belt was far stronger. Electron intensities reached the Kennel-Petschek limit, a theoretical ceiling where waves scatter particles so efficiently that further buildup becomes impossible. In practical terms, we found Uranus’s electrons to be as intense as physics would allow," said study lead author, Dr. Robert Allen of the Southwest Research Institute, to The Brighter Side of News.

At the same time, Voyager 2 measured very low densities of background plasma in the inner magnetosphere. For years, scientists struggled to explain how such strong relativistic electrons could exist alongside a weak ion population and sparse plasma.

A Solar Wind Clue

New analysis suggests the answer may lie in space weather. Evidence indicates that a large solar wind structure, called a co-rotating interaction region, or CIR, was passing over Uranus during the flyby. CIRs form where fast solar wind streams overtake slower ones, creating long-lasting disturbances.

Such a structure could have swept plasma out of parts of Uranus’s magnetosphere before Voyager 2 arrived. Combined with the planet’s offset magnetic field, the spacecraft may have sampled regions that were unusually empty at the time. If so, the flyby may not reflect typical conditions at all.

“Science has come a long way since the Voyager 2 flyby,” Allen said. “We decided to take a comparative approach looking at the Voyager 2 data and compare it to Earth observations we’ve made in the decades since.”

Lessons from Earth’s Radiation Belts

Since 1986, researchers have learned much more about radiation belts, especially around Earth. A major advance involved whistler-mode chorus waves, high-frequency signals that can rapidly boost electrons to extreme energies. These waves interact with lower-energy “seed” electrons and accelerate them through repeated encounters.

CIRs often trigger these processes at Earth. They drive persistent geomagnetic activity, supply seed particles, and sustain strong chorus waves. During such events, Earth’s electron belts can intensify dramatically, while proton belts remain relatively stable.

The Van Allen Probes mission, launched in 2012, tracked these effects in detail. Over more than a decade, the spacecraft showed that Earth’s proton belt changes little during disturbances. The electron belt, by contrast, varies widely and responds quickly to space weather.

A 2019 Earth Event Mirrors Uranus

Researchers compared Uranus’s 1986 flyby with a strong event at Earth in late August and early September 2019. Both periods occurred near solar minimum and involved repeated CIRs. At Earth, most of these disturbances boosted electrons to a few million electron volts. One CIR, however, pushed them up to 7.7 million electron volts.

During Voyager 2’s encounter, instruments recorded intense magnetic fields near Uranus and clear tail structures farther out. The spacecraft also detected powerful chorus waves, the strongest seen anywhere during the entire Voyager mission. These waves fell within a frequency range known to accelerate electrons efficiently.

Calculations show that the waves could strongly interact with electrons at energies Voyager 2 measured directly. Signs of substorm-like activity also appeared, suggesting a supply of fresh seed particles, much like Earth’s magnetosphere during storms.

“In 2019, Earth experienced one of these events, which caused an immense amount of radiation belt electron acceleration,” said Dr. Sarah Vines of the Southwest Research Institute, a co-author of the study. “If a similar mechanism interacted with the Uranian system, it would explain why Voyager 2 saw all this unexpected additional energy.”

A Shared Physics, Not a Fluke

The timing matters. At Uranus, peaks in energetic particle flux matched periods of intense chorus wave power. This pattern closely resembles Earth’s 2019 event, where electrons climbed steadily to higher energies while proton levels barely changed.

These similarities suggest that Uranus’s intense electron belt did not defy known physics. Instead, it may reflect the same wave-driven processes observed near Earth, amplified by Uranus’s low plasma density and unusual magnetic geometry. Such conditions may favor efficient acceleration, pushing electrons toward their theoretical limits.

“This is just one more reason to send a mission targeting Uranus,” Allen said. “The findings have some important implications for similar systems, such as Neptune’s.”

Why Uranus Still Holds Big Questions

If Voyager 2 caught Uranus during a storm-driven episode, scientists still need to know how often such events occur and how the belts behave over time. Uranus’s extreme seasons likely reshape its magnetosphere in ways never seen at Earth.

Researchers want to understand how particles enter the system, how waves scatter or accelerate them, and how the belts affect the planet’s moons and rings. They also want to track how auroras respond to this shifting environment.

Answering these questions requires an orbiter that can sample Uranus across seasons and regions. With modern instruments, such a mission could turn a fleeting snapshot into a full picture of one of the solar system’s strangest magnetic worlds.

Practical Implications of the Research

Understanding Uranus’s radiation belts helps scientists test whether space physics laws apply across very different environments.

These insights improve models used to protect spacecraft and astronauts from radiation. They also guide the design of future missions to the outer planets.

By showing that familiar processes can operate in extreme settings, the research strengthens confidence in predictions for other distant worlds, including Neptune and exoplanets with unusual magnetic fields.

Research findings are available online in the journal Geophysical Research Letters.

Related Stories

- Rethinking the “Ice Giants”: Uranus and Neptune may be rockier than we thought

- James Webb Telescope finds hidden moon orbiting Uranus

- Researchers solve the mystery of Uranus and Neptune's Magnetic Fields

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News' newsletter.

Joseph Shavit

Writer, Editor-At-Large and Publisher

Joseph Shavit, based in Los Angeles, is a seasoned science journalist, editor and co-founder of The Brighter Side of News, where he transforms complex discoveries into clear, engaging stories for general readers. With vast experience at major media groups like Times Mirror and Tribune, he writes with both authority and curiosity. His writing focuses on space science, planetary science, quantum mechanics, geology. Known for linking breakthroughs to real-world markets, he highlights how research transitions into products and industries that shape daily life.