Severe drought pushed the ‘hobbits’ of Flores toward extinction 61,000 years ago

New research shows drought, not humans, led to the disappearance of the “hobbits” on Flores.

Edited by: Joshua Shavit

Edited by: Joshua Shavit

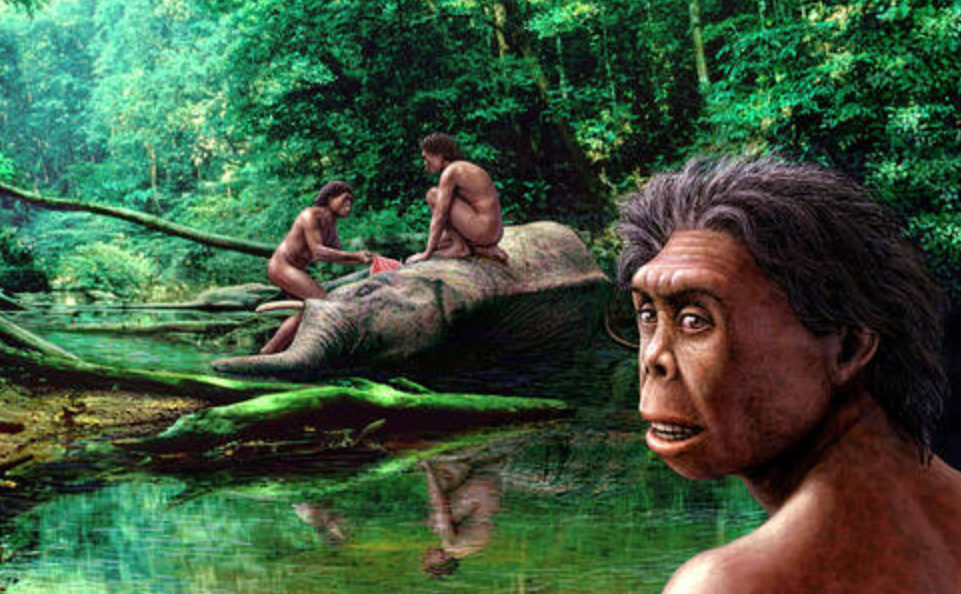

Climate records from cave stone and elephant teeth reveal how severe drought pushed Homo floresiensis toward extinction. (CREDIT: Wikimedia / CC BY-SA 4.0)

In 2003, bones pulled from a cave on the Indonesian island of Flores surprised scientists worldwide. The remains belonged to a small human relative no one had known about before: Homo floresiensis. Standing only about 3.5 feet tall, these people soon earned the nickname “hobbits.” Their discovery raised a major question. Did they survive long enough to meet modern humans, and did that contact end their story?

Later work changed that idea. Better dating showed the last known fossils of these people at Liang Bua cave were far older than first thought. The most recent bones there fall between 100,000 and 60,000 years old. Tools and animal remains found with them vanish by about 50,000 years ago. Modern humans, by contrast, did not reach the cave until around 46,000 years ago. That gap suggested the “hobbits” were gone before any meeting could happen, so researchers began to search for another cause.

A new study now offers a strong answer and it points to drought. An international team led by the University of Wollongong reports that long-term drying on Flores reshaped the landscape and drained crucial water sources. Their research, published in Communications Earth & Environment, shows the cave and its surroundings became steadily drier for thousands of years until life there could no longer be sustained.

“The ecosystem around Liang Bua became dramatically drier around the time Homo floresiensis vanished,” said UOW Honorary Professor Dr. Mike Gagan, the study’s lead author. “Summer rainfall fell and river-beds became seasonally dry, placing stress on both hobbits and their prey.”

The prey in question was a dwarf elephant called Stegodon florensis insularis. Weighing as much as a small car, these animals would have needed a steady supply of water. When rains weakened, elephants likely clustered around the few remaining sources. Humans would have followed. Both groups were tied to the same lifelines.

Reading Rainfall in Stone

To uncover what the climate was like tens of thousands of years ago, scientists turned to an unlikely record keeper: a stalagmite growing in Liang Luar cave, a little over a kilometer from Liang Bua. Layer by layer, dripping water had built the mineral column, locking in signals about rainfall.

By measuring tiny chemical changes inside the stone, including ratios of magnesium to calcium and forms of oxygen, the team rebuilt a history of rainfall from 91,000 to 47,000 years ago. The pattern was clear. Rain had been shrinking for millennia.

From about 76,000 to 61,000 years ago, annual rainfall dropped by roughly 37 percent. Conditions worsened from there. Between 61,000 and 55,000 years ago, summer rains fell to about half of what they are today. That stretch lines up closely with the last signs of both dwarf elephants and “hobbits” at Liang Bua.

To make sure the cave record matched real life above ground, the team studied elephant teeth. Like modern animals, Stegodon absorbed chemical traces from drinking water into their enamel. Those traces mirrored the cave signals, showing the same steady drying trend outside.

Out of 716 elephant bones from key sites, most came from a narrow band between 76,000 and 62,000 years ago. After that, the record thins fast. Only ten bones date later than 62,000 years ago, and the youngest is about 57,000 years old. Human fossils follow almost the same timeline, with the latest from around 61,000 years ago.

The River That Failed

One river likely tied the entire system together. The Wae Racang flows near Liang Bua and probably supplied water to both animals and people. The chemical match among most elephant teeth suggests they drank from the same place, almost certainly that river.

During wetter centuries, the Wae Racang would have flowed year-round. During long dry ones, it may have shrunk or stopped completely at times. Young elephants would have suffered most. Nearly all elephant remains at the cave belonged to juveniles or teens, animals less able to travel far in search of water.

At first, that stress may have helped hunters. Crowded animals near shrinking pools would have made easy targets. Over time, though, fewer elephants meant fewer meals. Water was also harder to find. Survival grew harder by the year.

Researchers describe three climate stages. The first, before 76,000 years ago, was wet and stable. Life thrived. The second brought strong seasons and longer dry periods. Grasslands probably expanded, which helped grazers but raised water stress. The third, after 61,000 years ago, marked a sharp and lasting drop in rain. Evidence from uranium in the stalagmite shows groundwater failed to refill as before. The region’s last reliable water likely broke down.

“Surface freshwater, Stegodon and Homo floresiensis all decline at the same time, showing the compounding effects of ecological stress,” said UOW Honorary Fellow Dr. Gert van den Berg. “Competition for dwindling water and food probably forced the hobbits to abandon Liang Bua.”

Not a Story of Human Conflict

Because modern humans reached the cave thousands of years later, direct conflict almost certainly did not cause the disappearance there. Some evidence suggests people like us passed through parts of Southeast Asia around the same era. Still, no signs show contact at Liang Bua.

The researchers suggest a simpler sequence. As rivers dried, animals moved or perished. Humans followed prey to better ground. What looks like extinction at one site may have begun as migration. Over time, shrinking habitats and smaller groups could have erased both species from the island.

Dr. Gagan notes that climate may still link the two human groups. “It’s possible that as the hobbits moved in search of water and prey, they encountered modern humans,” he said. “In that sense, climate change may have set the stage for their final disappearance.”

By pairing cave chemistry with fossils and teeth, scientists have built one of the most precise extinction timelines for an early human group. The picture that emerges is not one of battle but of thirst. When water failed, the web of life around it unraveled.

The “hobbits” did not vanish overnight. They faded as wells dried and rivers weakened. Their world, once rich with game and water, slowly became a place that could no longer support them.

Practical Implications of the Research

This research shows how shifts in rainfall can reshape entire ecosystems, including human communities. It offers a clear warning for today’s warming world, where fresh water grows less reliable in many regions.

The study also proves that caves and fossils can serve as powerful climate archives, helping scientists forecast how modern species, including humans, may respond to future drought.

By understanding how ancient populations struggled and adapted, researchers can better predict which regions now face the greatest risk.

Research findings are available online in the journal Communications Earth & Environment.

Related Stories

- Million-year-old sea crossing near ‘Hobbit’s’ island rewrites early human history

- New species of ancient humans rewrites the story of early human evolution

- What a new prehistoric ‘Hobbit’ creature tells us about evolution, mammals and dinosaurs

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News' newsletter.

Joseph Shavit

Science News Writer, Editor-At-Large and Publisher

Joseph Shavit, based in Los Angeles, is a seasoned science journalist, editor and co-founder of The Brighter Side of News, where he transforms complex discoveries into clear, engaging stories for general readers. With experience at major media groups like Times Mirror and Tribune, he writes with both authority and curiosity. His work spans astronomy, physics, quantum mechanics, climate change, artificial intelligence, health, and medicine. Known for linking breakthroughs to real-world markets, he highlights how research transitions into products and industries that shape daily life.