Scientists create Bose-Einstein condensate leading to a new fifth state of matter

Columbia physicists created a long-lived molecular BEC using microwaves, opening new paths for quantum simulation and materials research.

Edited By: Joseph Shavit

Edited By: Joseph Shavit

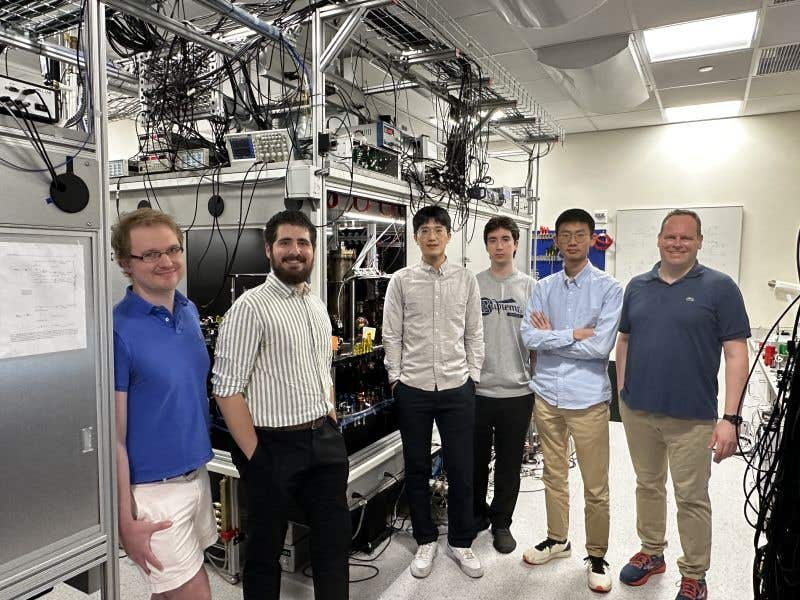

The members of the BEC team at Columbia, from left to right: associate research scientist Ian Stevenson, doctoral student Niccolò Bigagli, doctoral student Weijun Yuan, undergraduate student Boris Bulatovic, doctoral student Siwei Zhang, and principal investigator Sebastian Will. (CREDIT: Sebastian Will/ Will Lab/ Columbia University)

In a Columbia University laboratory in New York, physicist Sebastian Will and his team have reached one of ultracold physics’ long-running goals: turning molecules into a Bose-Einstein condensate. Their results, reported in Nature, rely on a key idea from theoretical collaborator Tijs Karman at Radboud University in the Netherlands, who helped design a way to stop fragile molecules from destroying one another during the final push to extreme cold.

The group created a Bose-Einstein condensate, or BEC, from sodium-cesium molecules, a polar species with an uneven electric charge distribution. The condensate formed at roughly 5 nanoKelvin, about minus 459.66 degrees Fahrenheit. It also lasted an unusually long time for this kind of experiment, about two seconds, giving researchers a wider window to probe how the system behaves.

“Molecular Bose-Einstein condensates open up whole new areas of research, from understanding truly fundamental physics to advancing powerful quantum simulations,” Will said. “This is an exciting achievement, but it’s really just the beginning.”

A century-old prediction meets modern control

The basic idea of a BEC traces back to 1924 and 1925, when Satyendra Nath Bose and Albert Einstein predicted that particles cooled close to a standstill would collapse into a single quantum state. For decades, that concept lived mostly on paper.

In 1995, researchers finally made BECs from atoms. The breakthrough later earned the 2001 Nobel Prize in Physics, around the time Will was starting his career in physics at the University of Mainz in Germany. Since then, atomic BECs have become standard tools for studying quantum behavior, including superfluidity, where a fluid flows without friction.

But molecules pose a harder challenge. Even simple two-atom molecules carry more internal motion than atoms do. They also collide and react in ways that can wipe out a carefully prepared sample before it cools far enough. For years, that made a molecular BEC feel like a finish line that kept moving.

A major step came in 2008, when Deborah Jin and Jun Ye at JILA in Boulder, Colorado, cooled potassium-rubidium molecules to about 350 nanoKelvin. That opened new directions in quantum simulation and ultracold chemistry. Still, the temperatures needed for a true molecular BEC sat much lower.

Why molecules kept slipping away

In practice, cooling depends on having a sample that survives long enough to be “evaporatively” cooled. The idea resembles blowing across hot coffee. The most energetic molecules leave first, and the remaining sample cools.

With molecules, that process kept failing because collisions were too destructive. Two-body and three-body loss processes could rapidly drain the sample. Even molecules chosen for chemical stability often showed short lifetimes, limiting how far cooling could go.

Fermionic molecules made some progress because quantum statistics can reduce how often particles clump together. Bosonic molecules, like sodium-cesium in this work, face the opposite tendency. They “bunch” more, increasing losses and raising the bar for any shielding method.

This is where the Columbia and Radboud collaboration mattered most. Karman’s theoretical work pointed toward “microwave shielding,” a way to dress molecules with electromagnetic fields so they repel each other at close range rather than collide and vanish.

Cooling with microwaves instead of heat

The Columbia team had already built an ultracold gas of sodium-cesium molecules in 2023 using laser cooling and magnetic techniques. To go further, they turned to microwaves, drawing on a long Columbia legacy in the field.

“Rabi was one of the first to control the quantum states of molecules and was a pioneer of microwave research,” Will said. “Our work follows in that 90-year-long tradition.”

Microwave shielding works by putting each molecule into a protected “dressed” state. In plain terms, the microwaves change how molecules look to each other during an approach. With the right settings, an energy barrier forms at short range, and the molecules bounce apart instead of reacting.

The group first showed that basic approach in earlier work, but a single microwave field came with a trade-off. Stronger shielding could reduce two-body loss, yet it also created conditions that increased three-body loss through long-range attraction and bound states that encourage recombination.

The new Nature result hinged on adding a second microwave field. One field was circularly polarized, and the other was linearly polarized. Together, they let the team cancel much of the long-range attraction while keeping the close-range repulsion. The outcome was closer to a purely repulsive interaction, which reduced both two-body and three-body losses enough to let evaporation finally work.

“This was fantastic closure for me,” said Niccolò Bigagli, who finished his PhD this spring and helped launch the lab’s effort. “We went from not having a lab set up yet to these fantastic results.”

What the molecular condensate makes possible

"The experiment began with about 30,000 sodium-cesium molecules in their electronic, vibrational and rotational ground states, held in an optical trap at about 700 nanoKelvin. Over about three seconds, we cooled them into the few-nanoKelvin range. During the evaporation sequence, condensation appeared once the sample crossed the threshold for quantum degeneracy, with more than 2,000 molecules near the transition. After further cooling, our team produced condensates with about 200 molecules and small thermal leftovers," Will told The Brighter Side of News.

The condensate’s measured 1/e lifetime was about 1.8 seconds, a standout for molecular systems. Many ultracold experiments run on timescales well under one second. “That will really let us investigate open questions in quantum physics,” said co-first author and PhD student Siwei Zhang.

Controlling molecular orientation is also part of the payoff. A polar molecule has a built-in separation of charge, which can support longer-range interactions than most atoms provide. “By controlling these dipolar interactions, we hope to create new quantum states and phases of matter,” said co-author and Columbia postdoc Ian Stevenson.

Ye, the JILA physicist who helped lead the 2008 milestone, called the new work a high level achievement. “The work will have important impacts on a number of scientific fields, including the study of quantum chemistry and exploration of strongly correlated quantum materials,” he commented. “Will’s experiment features precise control of molecular interactions to steer the system toward a desired outcome, a marvelous achievement in quantum control technology.”

Karman emphasized what it means when theory and experiment lock together. “We really have a good idea of the interactions in this system, which is also critical for the next steps, like exploring dipolar many-body physics,” he said. “We’ve come up with schemes to control interactions, tested these in theory, and implemented them in the experiment. It's been really an amazing experience to see these ideas for microwave ‘shielding’ being realized in the lab.”

One near-term target is using lasers to arrange the condensate in an optical lattice, an artificial crystal made of light. Atomic lattices already serve as quantum simulators, but atoms mostly interact at very short range. Molecules can bring longer-range behavior into those simulations. “The molecular BEC will introduce more flavor,” Will said.

Co-first author and PhD student Weijun Yuan pointed to geometry as another lever. “We would like to use the BECs in a 2D system. When you go from three dimensions to two, you can always expect new physics to emerge,” he said.

“It seems like a whole new world of possibilities is opening up,” Will said.

Practical Implications of the Research

This molecular condensate gives researchers a cleaner way to test ideas about materials whose behavior depends on strong, long-range interactions. If the system can be tuned from weakly interacting to strongly interacting regimes, it could help explain how complex quantum phases form, including phases that remain difficult to compute with standard methods. That matters for condensed matter physics, where better models can clarify why some solids show unusual electrical or magnetic behavior.

The work also strengthens the toolbox for quantum simulation. With atoms, many simulations rely on short-range contact effects. Polar molecules can extend that reach, letting experiments better mimic real materials where particles influence one another over longer distances.

Over time, this could guide the design of new quantum devices, improve control methods used across quantum technology labs, and expand ultracold chemistry into a setting where reactions and collisions can be studied with finer precision.

Research findings are available online in the journal Nature.

Related Stories

- Quantum liquid crystal: Scientists discover a new 5th state of matter

- A flash of light just redefined what we know about matter

- Swiss physicists detect traces of a potential fifth force of nature

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News' newsletter.

Joshua Shavit

Writer and Editor

Joshua Shavit is a NorCal-based science and technology writer with a passion for exploring the breakthroughs shaping the future. As a co-founder of The Brighter Side of News, he focuses on positive and transformative advancements in technology, physics, engineering, robotics, and astronomy. Joshua's work highlights the innovators behind the ideas, bringing readers closer to the people driving progress.