Scientists bend magnetic fields around real-world objects to create ‘invisibility cloaks’

Engineers have developed a new way to design magnetic cloaks for complex shapes using materials already on the market.

Edited By: Joseph Shavit

Edited By: Joseph Shavit

New research shows magnetic cloaks can be built for real-world shapes using superconductors and soft magnets. (CREDIT: AI-generated image / The Brighter Side of News)

For nearly 20 years, physicists and engineers have chased the idea of invisibility. Early efforts focused on hiding objects from light using so-called metamaterials with extreme and often unrealistic properties. Later work extended the idea to sound, heat, and electric and magnetic fields. In most cases, these designs stayed confined to theory or worked only for ideal shapes that rarely exist outside the lab.

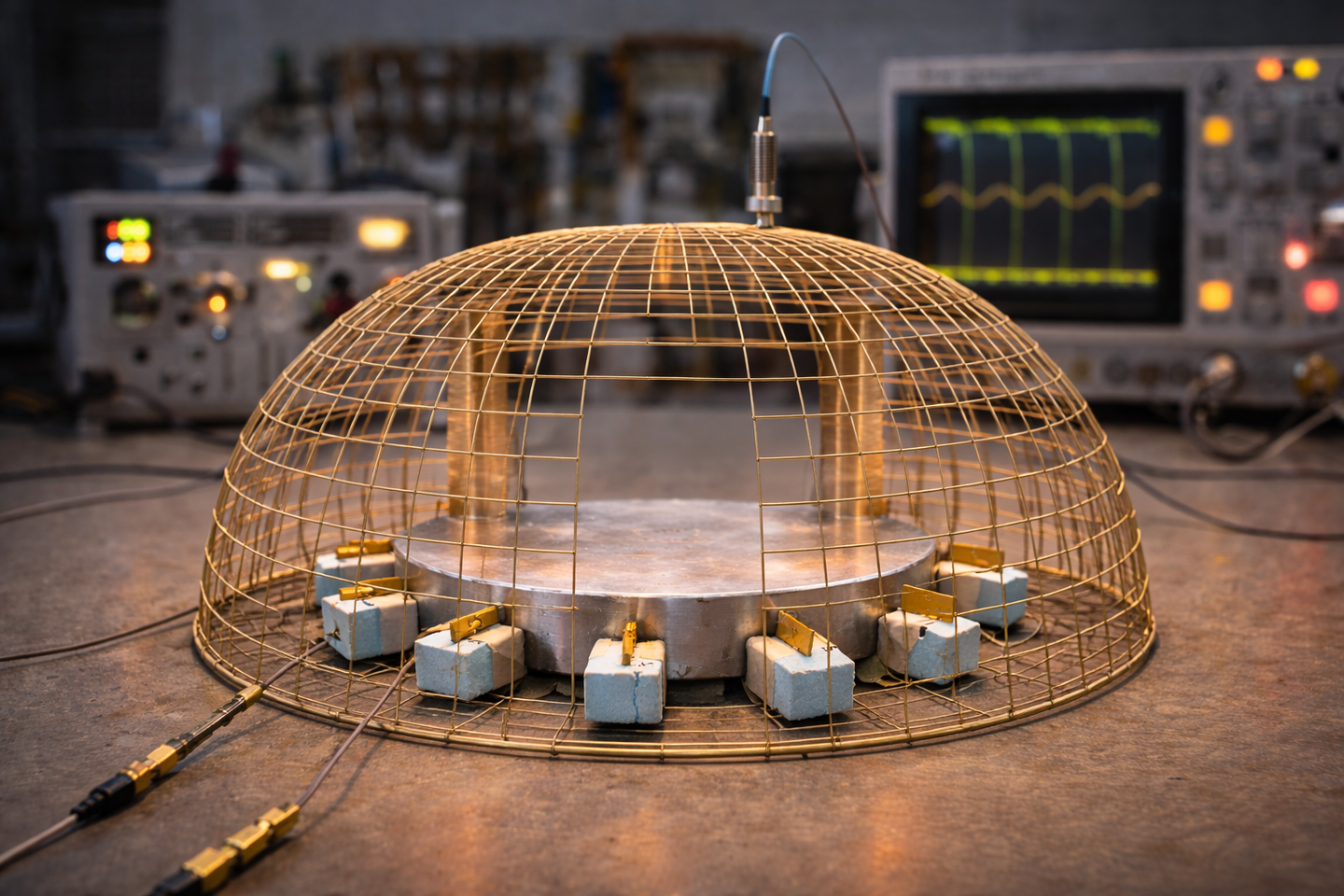

Researchers at the University of Leicester are now pushing magnetic cloaking closer to everyday use. In a new study published in Science Advances, engineers from the university’s School of Engineering present a design framework that allows magnetic cloaks to be built around objects of almost any shape using materials that already exist.

At the center of the work is a familiar pairing. Magnetic cloaks often rely on two layers. The inner layer is a superconductor, which naturally pushes magnetic fields away. The outer layer is a soft ferromagnet, which can guide magnetic field lines back into their original paths. When tuned correctly, the two layers work together so the magnetic field outside the object looks undisturbed, as if nothing were there.

Why Shape Has Been the Biggest Barrier

Earlier experiments showed that this approach works well for simple shapes. Long cylinders and spheres with perfect symmetry could be cloaked using a superconducting core wrapped in a ferromagnetic shell. In these ideal cases, researchers could even calculate an exact value for the magnetic permeability of the outer layer to achieve near-perfect cloaking. Laboratory tests confirmed that these designs could hide objects from static and low-frequency magnetic fields.

The problem is that real devices rarely look like perfect cylinders. Power cables, electronic housings, and scientific instruments often have square edges, sharp corners, or complex outlines. When the same cloaking rules are applied to these shapes, the magnetic field distorts badly, and the illusion breaks down.

The Leicester team set out to solve this problem directly. Instead of relying on formulas that only work for ideal geometries, they built a general optimization framework based on the full Maxwell equations. This approach lets a computer search for the best magnetic properties needed to restore the field outside an object, no matter how irregular the shape inside may be.

Testing the Method on Known Ground

To check that their framework worked, the researchers started with a familiar test. They modeled a hollow cylindrical superconductor coated with a ferromagnetic shell. Because the exact solution for this case is already known, it offered a clear benchmark.

"Our optimization algorithm searched for the best constant permeability for the ferromagnetic layer. The result matched the analytic solution with more than 99 percent accuracy when the outer shell had the right thickness. This close agreement showed us that the numerical method could reliably reproduce established theory," Harold Ruiz, a researcher at the University of Leicester School of Engineering told The Brighter Side of News.

"With that confidence, our team moved beyond circles. We tested square and diamond-shaped pipes, which interact with magnetic fields in very different ways. In a square pipe, we found that the field strikes flat faces head-on. In a diamond shape, the field meets sharp corners at an angle. These differences change how the superconducting layer repels the field," he continued.

Using a single, uniform ferromagnetic shell failed in both cases. The solution was to allow the magnetic permeability of the outer layer to vary from place to place. By tailoring this variation, the algorithm could bend the field lines back into position outside the cloak.

For the diamond shape, the optimized cloak reduced external field distortion to about 0.01 percent. For the square shape, distortion dropped to roughly 0.31 percent. In both cases, the surrounding magnetic field looked almost identical to the original background.

Making the Designs Buildable

Perfect performance came with a drawback. The best solutions relied on sharp spikes in magnetic permeability and sudden changes across the ferromagnetic layer. Such extreme and uneven properties would be very difficult to manufacture.

To address this, the researchers introduced a regularization step. This part of the optimization penalizes abrupt changes in permeability and favors smoother, more uniform material profiles. By tuning this parameter, they accepted a small loss in cloaking performance in exchange for designs that are far more realistic.

The effect was clear. In the diamond-shaped cloak, peak permeability dropped from about 11.5 to 7.3 with only a tiny increase in distortion. In the square cloak, peak values fell from more than 80 to about 11, while the field outside remained largely undisturbed.

The team also explored shell thickness. Making the ferromagnetic layer slightly thicker allowed lower peak permeability values. Across several shapes, modest increases in thickness reduced extreme material demands by up to nearly 40 percent.

Tackling Real Cable Geometries

The most demanding test involved a complex, multi-lobed cross section inspired by high-voltage power cables. In this geometry, the superconducting layer alone created uneven shielding. Some regions experienced near-zero fields, while others showed strong distortion.

Even so, the optimization framework found a workable solution. The combined superconducting and ferromagnetic cloak restored the external field to within a few percent of its original pattern across most of the region. Regularization again smoothed extreme material values while keeping performance within practical limits.

Behind these designs lies a detailed physical model. The simulations operate in a low-frequency regime suitable for real power systems. The superconducting layer is modeled using parameters from commercially available high-temperature superconducting tapes operating at liquid nitrogen temperatures. Field strengths span values relevant to technologies such as medical imaging systems.

Looking Ahead

For you, the key takeaway is that magnetic cloaking is no longer limited to tidy laboratory shapes. By combining realistic material models with flexible optimization, the Leicester researchers show that cloaks can be tailored to square housings, faceted pipes, and complex cable layouts.

The work points toward practical fabrication routes. Superconducting tapes could be shaped around custom supports, while outer shells could be formed from soft magnetic composites with adjustable properties.

“Magnetic cloaking is no longer a futuristic concept tied to perfect analytical conditions. This study shows that practical, manufacturable cloaks for complex geometries are within reach, enabling next-generation shielding solutions for science, medicine, and industry,” Ruiz said.

He added, “Our next step is the fabrication and experimental testing of these magnetic cloaks using high-temperature superconducting tapes and soft magnetic composites. We are already planning follow-up studies and collaborations to bring these designs into real-world settings.”

Practical Implications of the Research

This research could reshape how sensitive technologies are protected from magnetic interference. As devices become more precise, stray magnetic fields increasingly cause errors, noise, or failures.

Custom-shaped magnetic cloaks could shield components in hospitals, power grids, laboratories, and aerospace systems without disturbing surrounding equipment.

In the long term, these designs may help protect fusion reactors, improve medical imaging reliability, and support emerging quantum sensors and navigation tools. By showing that tailored cloaks can be built from available materials, the study brings magnetic invisibility closer to everyday use.

Research findings are available online in the journal Science Advances.

Related Stories

- Scientists create thermal-invisible surfaces by mimicking clouds

- AI chatbots can hide secret messages invisible to surveillance

- World First: MIT scientists demonstrate how to make invisible matter

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News' newsletter.

Joshua Shavit

Writer and Editor

Joshua Shavit is a Nor Cal-based science and technology writer with a passion for exploring the breakthroughs shaping the future. As a co-founder of The Brighter Side of News, he focuses on positive and transformative advancements in technology, physics, engineering, robotics and astronomy. Joshua's work highlights the innovators behind the ideas, bringing readers closer to the people driving progress.