Quantum technologies have reached a critical stage in their growth

New study finds that quantum technologies have reached a critical stage, echoing the early days of classical computing and highlighting what must change to scale them.

Edited By: Joseph Shavit

Edited By: Joseph Shavit

A new Science paper explains why quantum technology faces its biggest scaling challenge yet and how history offers a path forward. (CREDIT: Shutterstock)

Quantum information science is no longer confined to chalkboards and controlled laboratory tests. You now see working quantum computers, early quantum networks, and ultra-sensitive quantum sensors moving toward practical use. The moment echoes the early decades of classical computing, when microelectronics began to shift from theory into tools that reshaped society. A new study argues that quantum technology now sits at a similar turning point.

The paper, published in the journal Science, brings together researchers from the University of Chicago, Stanford University, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, the University of Innsbruck in Austria, and Delft University of Technology in the Netherlands. It reviews the current state of quantum hardware and outlines what must change to build large, reliable quantum systems.

“This transformative moment in quantum technology is reminiscent of the transistor’s earliest days,” said lead author David Awschalom, the Liew Family Professor of molecular engineering and physics at the University of Chicago and director of the Chicago Quantum Exchange and the Chicago Quantum Institute. “The foundational physics concepts are established, functional systems exist, and now we must nurture the partnerships and coordinated efforts necessary to achieve the technology’s full, utility-scale potential. How will we meet the challenges of scaling and modular quantum architectures?”

Lessons from the rise of classical computing

Looking back at classical computing helps frame the challenge ahead. Over roughly 75 years, the cost of a basic computing operation fell by more than 14 orders of magnitude. Transistor counts climbed from a few thousand in the early 1970s to nearly 100 billion on modern chips. These gains did not come from a single discovery but from repeated shifts in materials, device design, and system architecture.

Progress followed a top-down path. System needs shaped circuit design, which then dictated materials and fabrication methods. Replacing silicon dioxide with hafnium dioxide in transistors or building three-dimensional NAND memory came from clear performance demands, not curiosity alone. Open, precompetitive research also played a central role, allowing industry, academia, and government labs to share knowledge and avoid wasted effort.

The authors argue that quantum technologies must follow a similar model. Open science, realistic timelines, and strong collaboration will matter as much as any single breakthrough.

Measuring readiness without losing perspective

To assess where the field stands, the researchers compared six leading quantum hardware platforms: superconducting qubits, trapped ions, spin defects in solids, semiconductor quantum dots, neutral atoms, and photonic qubits. They evaluated each platform across computing, simulation, networking, and sensing using technology readiness levels, or TRLs.

TRLs range from 1, where basic principles are observed, to 9, where systems operate in real-world settings. To avoid a narrow view, the authors drew on assessments from large language models, including ChatGPT and Gemini, to capture a broad picture of perceived maturity.

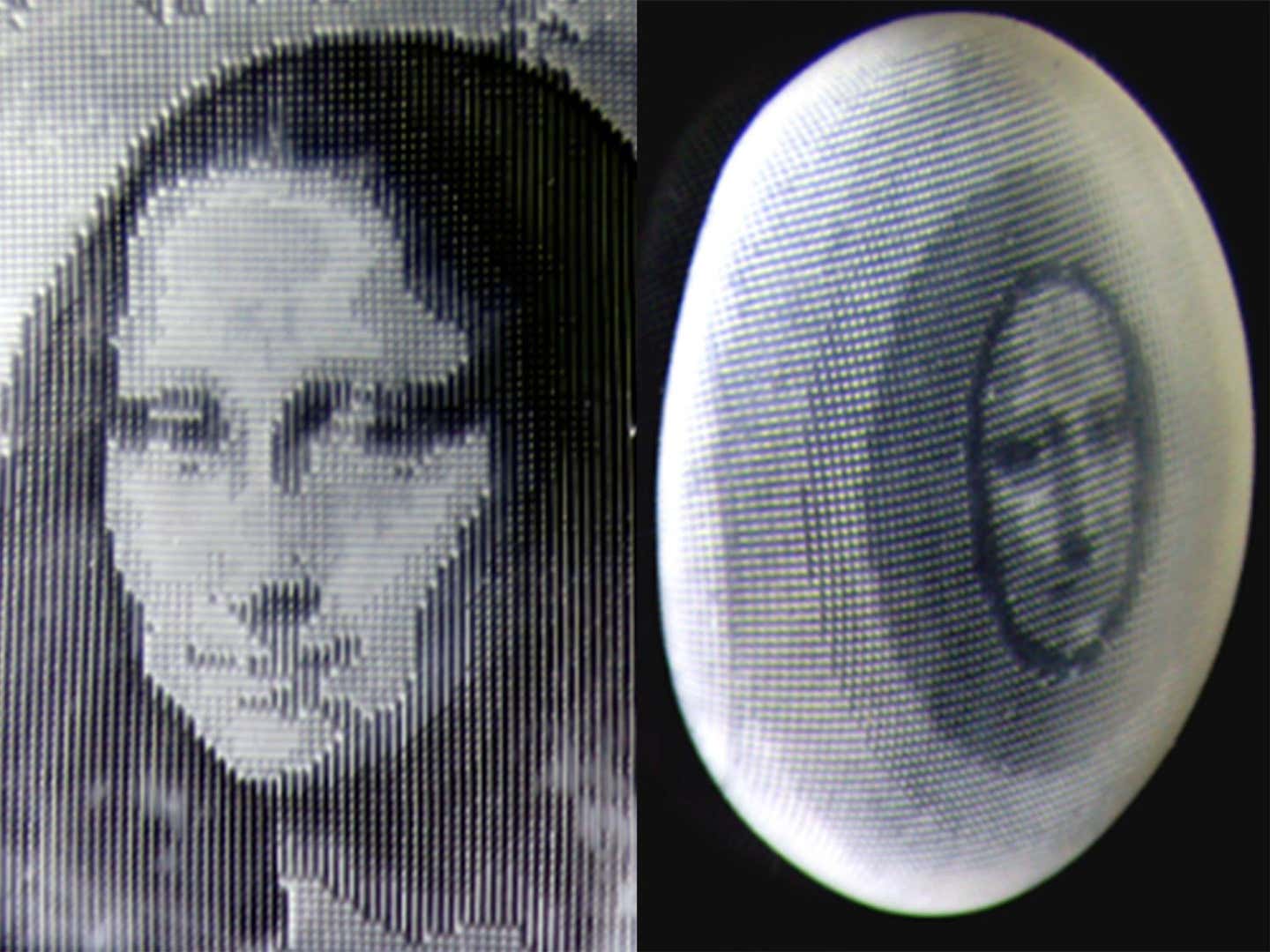

A key point is context. A high TRL does not mean a technology is close to its final form. The Intel 4004 processor in 1971 ranked high for its time because it worked in real products, even though it was limited by today’s standards. Quantum systems today occupy a similar position.

“While semiconductor chips in the 1970s were TLR-9 for that time, they could do very little compared with today’s advanced integrated circuits,” said coauthor William D. Oliver, the Henry Ellis Warren (1894) Professor of electrical engineering and computer science and professor of physics at MIT. “Similarly, a high TRL for quantum technologies today does not indicate that the end goal has been achieved, nor does it indicate that the science is done and only engineering remains.”

A diverse landscape of quantum hardware

Each quantum platform brings strengths and limits. Superconducting qubits and semiconductor quantum dots act as engineered “artificial atoms” that operate at extremely low temperatures. Superconducting systems already host more than 100 qubits with fast operation and high accuracy. Quantum dots offer smaller size and dense integration but face wiring and control challenges.

Spin defects, such as color centers in diamond, stand out for long coherence times and strong optical links. These systems already support small quantum networks over tens of kilometers of fiber. Trapped ions and neutral atoms benefit from natural uniformity and long-lived quantum states, with arrays now reaching hundreds or thousands of atoms.

Photonic approaches aim to compute using entangled light itself. While losses still limit scale, new photon sources and optical devices are improving rapidly. Across all platforms, photonics plays a central role in control, readout, and networking.

Shared obstacles to scaling

"Despite progress, scaling any platform to millions of qubits presents similar barriers," Awschalom explained to The Brighter Side of News. "Fabrication must become more reliable and compatible with large-scale manufacturing. Wiring poses another constraint, since most systems still rely on individual control lines for each qubit. Calibration grows harder as devices expand, with tiny differences between qubits demanding constant adjustment," he continued.

Power, size, and cooling add further pressure. Many systems depend on bulky cryogenic equipment or high-power lasers. Simply building larger versions of today’s machines will not work.

"We grouped these limits into four themes: materials and fabrication, wiring, calibration and control, and size and power. Solving them will require coordinated advances rather than isolated fixes," Awschalom said.

Modularity as a path forward

To overcome these limits, the paper highlights modular architectures. Instead of one massive chip, a quantum system could be built from smaller, repeatable modules connected by quantum links. Each module would manage its own qubits, control electronics, and cooling, while networks of modules would share quantum information.

This approach mirrors classical data centers, where complexity stays manageable through replication. It also allows flexibility, letting different modules specialize in memory, processing, or networking.

Achieving this vision depends on reliable quantum connections and hybrid devices that link different technologies. Photonics, especially new low-loss materials and integrated optical components, sits at the center of this effort.

A long-term global effort

Quantum hardware has advanced rapidly over the past decade, but the authors stress patience. Many classical technologies took decades to mature. Quantum systems will likely follow a similar timeline, shaped by sustained investment and shared goals.

For you as a reader, the message is grounded. Quantum technologies are real and advancing, but they remain early in their development. Their future depends on careful design choices, collaboration across sectors, and a willingness to learn from the past.

Research findings are available online in the journal Science.

Related Stories

- Reading a quantum clock takes more energy than operating it

- New quantum sensors aim to detect hidden forces behind dark matter

- Oxford physicists achieve teleportation between two quantum supercomputers

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News' newsletter.

Joshua Shavit

Writer and Editor

Joshua Shavit is a NorCal-based science and technology writer with a passion for exploring the breakthroughs shaping the future. As a co-founder of The Brighter Side of News, he focuses on positive and transformative advancements in technology, physics, engineering, robotics, and astronomy. Joshua's work highlights the innovators behind the ideas, bringing readers closer to the people driving progress.