New solid-state battery design retains 75% capacity after 1,500 cycles

PSI researchers densified a solid electrolyte and added a 65 nm LiF layer, keeping 75% capacity after 1,500 cycles.

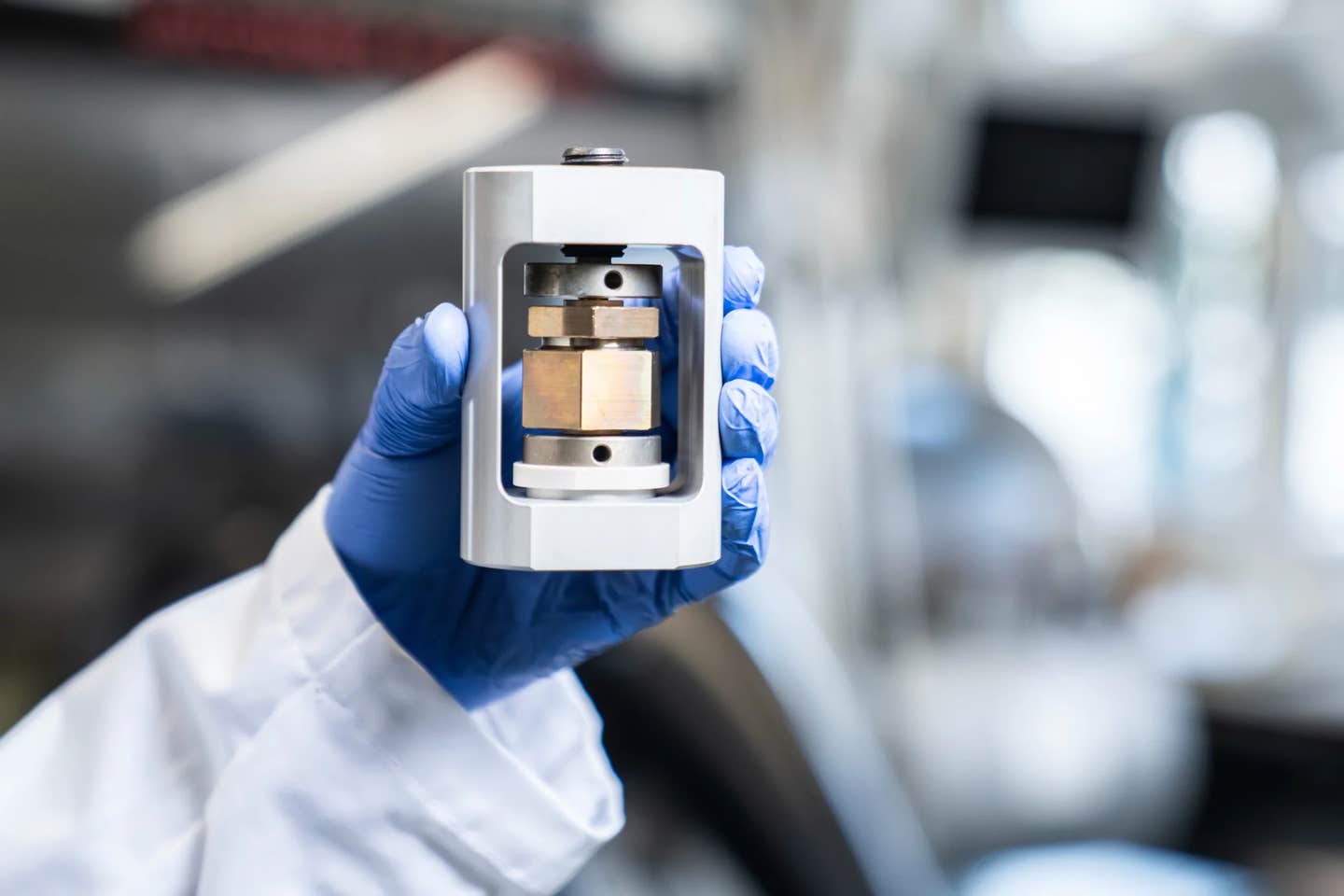

A new PSI method combines gentle sintering and an ultra-thin LiF layer to curb dendrites and stabilize solid-state lithium metal batteries. (CREDIT: PSI)

A battery that charges fast, holds more energy, and stays safer under stress has become a kind of modern promise. You hear it in electric car ads, in phone launches, and in grid storage plans. Yet the technology behind that promise keeps running into the same hard walls. A new advance from the Paul Scherrer Institute, known as PSI, suggests one of those walls may finally be cracking.

Researchers at PSI report a production approach that tackles two stubborn problems in lithium metal all-solid-state batteries, a next-generation design that replaces flammable liquid electrolytes with a solid material. The team says the method helps stop lithium dendrites, which can trigger short circuits. It also steadies the fragile boundary where lithium metal touches the solid electrolyte.

The idea sounds technical, but the goal is simple. You want a battery that keeps working after thousands of charge cycles. You also want it to survive fast charging without developing internal damage. The PSI team argues its strategy brings that goal closer.

Why Solid-State Batteries Draw So Much Hope

Most lithium-ion batteries today rely on a liquid electrolyte. It helps lithium ions move between electrodes during charging and discharging. The drawback is clear. Liquids can be flammable. That risk forces designers to add layers of protection.

All-solid-state batteries avoid that liquid. In principle, this makes them inherently safer. It also opens the door to higher energy storage, faster charging, and longer life. That is why researchers see them as a key option for electromobility, mobile electronics, and stationary energy storage.

Yet the market has waited. The delay is not a lack of ambition. It is physics and chemistry at work inside the cell. Two problems in particular have blocked progress.

First, lithium dendrites can grow from the lithium metal anode. These tiny, needle-like structures can push into the solid electrolyte, reach toward the cathode, and create an internal short circuit.

Second, the interface between lithium metal and the solid electrolyte can be unstable. That instability harms performance and erodes reliability over time.

PSI’s new work targets both problems at once, with a combination approach that focuses on the electrolyte body and the anode interface.

The Electrolyte at the Center of the Breakthrough

The study centers on an argyrodite-type solid electrolyte called Li₆PS₅Cl, shortened as LPSCl. It is a sulphide-based material made of lithium, phosphorus, and sulphur. Researchers value it because it has high lithium-ion conductivity. That means lithium ions can move rapidly through it, which is crucial for high power and efficient charging.

Yet LPSCl has had a manufacturing problem. It is hard to densify properly. If the electrolyte contains voids or porous regions, those weak pathways can become an invitation for dendrites.

Researchers have typically tried two main densification routes. One is very high pressure at room temperature. The other is a classic sintering approach, which combines pressure with temperatures above 400 degrees Celsius so particles fuse and pack tightly.

Both have downsides. Room-temperature pressing can leave a porous microstructure and can drive excessive grain growth. High-temperature processing risks breaking down the electrolyte.

PSI’s team needed a method that densifies LPSCl without destabilizing it. They found it by changing the temperature strategy.

A Gentler Heat, a Denser Structure

Mario El Kazzi, head of the Battery Materials and Diagnostics group at PSI, led the work. “We combined two approaches that, together, both densify the electrolyte and stabilize the interface with the lithium,” he said.

Instead of classic sintering, the researchers used what they describe as gentle sintering. They compressed the mineral under moderate pressure at a moderate temperature of about 80 degrees Celsius.

That lower heat matters. It allows particles to rearrange and bond tightly while preserving chemical stability. The process helps close small cavities and reduce porous areas. The result is a compact, dense microstructure that resists dendrite penetration. At the same time, it remains well suited for rapid lithium-ion transport.

Still, the team found that densification alone did not fully solve the problem. A battery also needs a stable interface when it operates at high current densities, especially during rapid charging and discharging. That is where the second part of their strategy comes in.

A 65-Nanometre Shield at the Interface

To stabilize the interface, the researchers added a thin layer of lithium fluoride, or LiF, on the lithium surface. The coating measured only 65 nanometres thick. The team applied it uniformly by evaporating LiF under vacuum, creating an ultra-thin passivation layer.

This layer serves two roles.

First, it helps prevent electrochemical decomposition of the solid electrolyte when it contacts lithium metal. That suppression also reduces the formation of “dead,” inactive lithium, which can build up and reduce usable capacity.

Second, the coating acts as a physical barrier against dendrite growth. In effect, it makes it harder for needle-like structures to dig into the electrolyte.

Together, gentle sintering and the LiF layer create a system that addresses both the body of the electrolyte and the vulnerable boundary at the anode.

Button Cells That Keep Going, and Going

The test results came from laboratory button cells. PSI reports strong performance under demanding conditions.

“Its cycle stability at high voltage was remarkable,” said Jinsong Zhang, a doctoral candidate and lead author of the study.

After 1,500 charge and discharge cycles, the cell retained about 75 percent of its original capacity. In simple terms, three-quarters of the lithium ions still migrated between electrodes as designed. Zhang called it “An outstanding result. These values are among the best reported to date.”

The team frames the result as more than a single strong battery. It is a demonstration that two persistent problems can be suppressed together. Dendrite growth and interfacial instability often appear like separate battles. This approach treats them as linked.

"There are practical benefits for manufacturing. The low-temperature process saves energy, which can reduce costs. That also brings a possible environmental advantage, since it reduces energy demand during production," Kazzi told The Brighter Side of News.

“Our approach is a practical solution for the industrial production of argyrodite-based all-solid-state batteries. A few more adjustments; and we could get started,” he continued.

Practical Implications of the Research

This work offers a clearer route toward batteries that are safer and more durable, especially in applications that demand fast charging. If dendrites and unstable interfaces become less of a threat, designers can more confidently use lithium metal anodes, which are central to higher energy storage in solid-state designs. That could translate into electric vehicles that travel farther per charge, and devices that maintain useful battery life longer before needing replacement.

The study also pushes research toward manufacturing methods that match real-world constraints. Gentle sintering at about 80 degrees Celsius uses far less heat than classic sintering above 400 degrees Celsius. That low-temperature approach can lower energy use in production and reduce the risk of damaging sensitive electrolyte materials. If industry can adopt such methods, large-scale solid-state battery production may become more feasible and less expensive.

Finally, the combined strategy provides a testable blueprint for other solid electrolytes and interface coatings. Researchers can build on this approach, compare materials, and refine coatings to improve performance at high current densities. That shared direction can speed progress, reduce trial-and-error work, and help the field move toward batteries that support cleaner transport and steadier renewable energy storage.

Research findings are available online in the journal Advanced Science.

Related Stories

- Breakthrough battery technology knows whether your EV will make it back home

- Next-gen wireless chip boosts battery life and reduces signal errors

- World’s smallest battery works in blood to power medical sensors

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News' newsletter.

Shy Cohen

Science & Technology Writer