Harvard scientists tell a ‘hot’ story about beetles and plant sex

Long before colorful flowers evolved, ancient cycads attracted beetle pollinators by heating their cones.

Edited By: Joseph Shavit

Edited By: Joseph Shavit

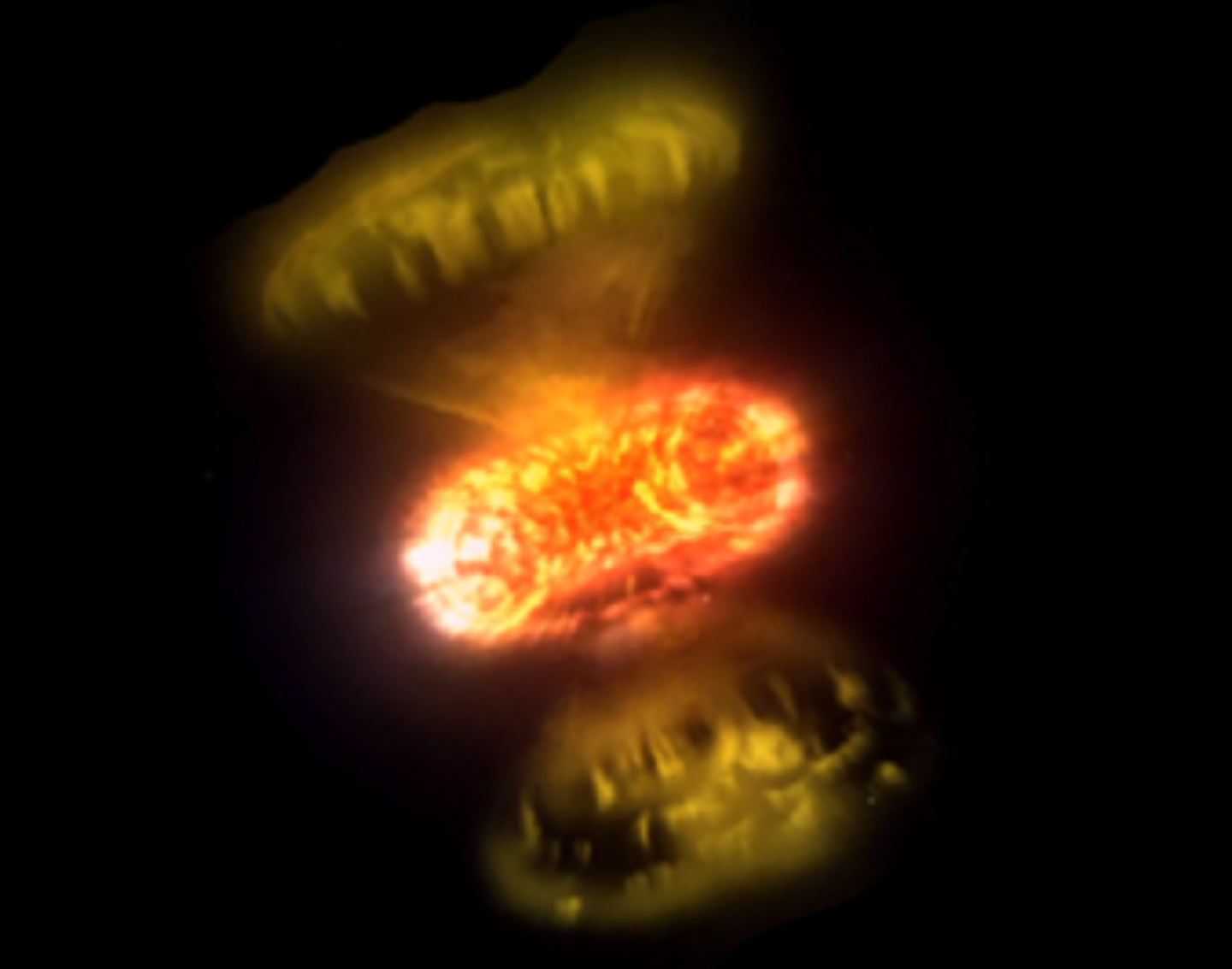

New research shows cycads heat their cones and beetles sense infrared, revealing one of Earth’s oldest pollination systems. (CREDIT: Science)

Flowers are often described as visual advertisements, using bright colors and strong scents to draw in insects. Yet long before petals and pigments dominated the landscape, some plants relied on a different signal altogether: heat. New research shows that cycads, among the oldest living seed plants, warm their reproductive cones to attract beetle pollinators that can sense infrared radiation. This form of communication likely shaped one of the earliest pollination systems on Earth.

Cycads are gymnosperms, meaning they produce seeds without flowers. Instead, they grow cones, with male and female cones appearing on separate plants. These structures are not passive. During specific times of day, they heat up dramatically, reaching temperatures more than 35 degrees Celsius above the surrounding air. That level of metabolic activity rivals that of a hummingbird in flight.

For decades, scientists believed this heat mainly helped spread scent or protect tissues from cold. The new study shows something more direct. Heat itself acts as a signal. Beetle pollinators detect infrared radiation coming from cones and use it to decide where to land and when to move between male and female plants.

The work, led by Wendy Valencia-Montoya of Harvard University and published in Science, identifies infrared radiation as a pollination cue for the first time. It also suggests that thermal signaling predates colorful flowers by hundreds of millions of years.

“This is basically adding a new dimension of information that plants and animals are using to communicate that we didn't know about before,” Valencia-Montoya said. “We knew of scent and we knew of color, but we didn't know that infrared could act as a pollination signal.”

How Cycad Cones Generate Heat

The researchers focused on Zamia furfuracea, a cycad native to Mexico often called the cardboard palm. Thermal imaging showed that heat production is concentrated in the cone scales, known as sporophylls. These tissues are packed with mitochondria and starch granules, the raw materials needed for intense respiration.

At the genetic level, the cones activate an alternative metabolic route. They increase expression of a gene called AOX1, which allows mitochondria to release energy directly as heat instead of storing it as ATP. Genes involved in moving and breaking down starch also increase their activity. After heating events, starch reserves are depleted.

Heat production follows a strict daily rhythm. Circadian clock genes switch on in the afternoon, and cones produce a single burst of heat that peaks in the early evening. This pattern holds across 17 Zamia species and the closely related Microcycas calocoma. Thermogenesis is costly, precise, and limited to reproductive organs.

Male and female cones do not heat at the same time. In Z. furfuracea, male cones warm first and then cool. Female cones reach peak temperatures roughly three hours later. That staggered timing hinted that heat might guide pollinators between the sexes.

Following the Heat in the Field

To test that idea, the team tracked the behavior of Rhopalotria furfuracea, the beetle that pollinates Z. furfuracea. In open-field experiments, male and female plants were placed 50 meters apart. Beetles dusted with ultraviolet fluorescent dye moved from male to female cones, carrying pollen with them.

The beetles consistently gathered on the warmest parts of cones. In controlled cage experiments, beetle numbers rose and fell in step with cone temperatures. As male cones cooled and female cones warmed, beetles shifted accordingly. Heat appeared to function as a timed signal that first attracts and then redirects pollinators.

To separate heat from scent or humidity, researchers used three-dimensional printed cone models. Some were heated to match real cone temperatures, while others remained cool. The models were coated with odorless sticky material so beetles could not sense temperature by touch.

In both field and cage trials, beetles strongly preferred the warm models. More than 1,500 beetles across dozens of experiments chose heated cones, with results far beyond chance. When heated models were placed under polyethylene film that blocks air flow but allows infrared radiation to pass, beetles still favored them. This showed that infrared radiation alone can guide pollinators at short to moderate distances.

Beetles Equipped to Sense Infrared

If plants broadcast heat, pollinators need the tools to receive it. The key lies in the beetles’ antennae. Using scanning electron microscopy, the team examined the antenna tips of R. furfuracea and another cycad pollinator, Pharaxonotha floridana. The tips were crowded with tiny sensory structures called coeloconic sensilla, known in other insects to detect temperature.

Electrophysiology experiments confirmed their function. Some sensilla contained neurons that fired rapidly when warmed. Others housed paired neurons, one activated by heat and the other suppressed. When researchers removed the antenna tips, beetles no longer responded to infrared radiation but still reacted to cone scent.

Gene expression analyses pointed to a molecular sensor behind this ability. A specific form of the ion channel TRPA1, called TRPA1(B), was abundant in the antennae. This protein also helps snakes and mosquitoes sense warmth. When expressed in the lab, beetle TRPA1(B) opened at temperatures only slightly above ambient. A related form, TRPA1(A), was much less sensitive.

The researchers identified a chemical blocker, AM-0902, that inhibits TRPA1(B). When applied to beetle antennae, it eliminated responses to infrared radiation without affecting reactions to odor. This confirmed that TRPA1(B) is essential for thermal sensing.

A System Older Than Flowers

Each beetle species showed sensitivity tuned to its host plant’s temperature range. P. floridana responds to lower cone temperatures than R. furfuracea, matching the plants they pollinate. These beetles belong to families that diverged more than 140 million years ago, suggesting that infrared-guided pollination may be widespread among thermogenic plants.

Cycad pollinators have limited color vision. They are dichromatic, sensitive mainly to ultraviolet and green light. Measurements of cone reflectance showed little contrast in this visual space. In contrast, flowering plants display strong color contrast under bee and butterfly vision, which is more complex.

When researchers mapped heat production and color diversity across seed plant evolution, a clear pattern emerged. Ancient lineages, including cycads, relied heavily on thermogenesis. Younger groups invested in color instead. Statistical models showed a strong negative relationship between heat signaling and color diversity.

Fossil evidence suggests that thermogenesis arose near the origin of cycads about 275 million years ago, well before dinosaurs. Beetles likely served as some of the first animal pollinators. Only later did bees and butterflies rise alongside colorful flowers.

“The fact that the infrared signal had remained unrecognized for so long probably reflects our own sensory bias,” Valencia-Montoya said. “All the sensory cues that have been recognized very fast are the ones that we can perceive.”

"Over hundreds of millions of years, this early “language” of heat likely shaped the first biotic pollination mutualisms, especially in nocturnal, beetle-dominated ecosystems. As new pollinator groups with more complex color vision rose to prominence, plants that could produce a wider palette of pigments gained an advantage," Valencia-Montoya shared with The Brighter Side of News.

"The result is the modern landscape, where most people notice flowers for their dazzling colors, rarely suspecting that one of the oldest pollination signals is invisible to human eyes and carried not by light we can see, but by warmth", she concluded.

Practical Implications of the Research

Understanding thermal signaling reshapes how scientists think about plant–pollinator communication. It reveals a sensory channel that has gone unnoticed because humans cannot see or feel it easily. This insight could guide conservation of endangered cycads by clarifying how their specialized pollinators locate them.

The findings may also inspire new research into insect sensory biology and the evolution of communication systems. Beyond ecology, infrared-based signaling could inform designs in robotics or agriculture, where subtle thermal cues may guide behavior more efficiently than visual ones.

Research findings are available online in the journal Science.

Related Stories

- Plants will take millions of years to recover from global warming, study finds

- Breakthrough sunlight-powered system captures carbon just like plants

- Ice age plants reveal clues about climate change and mass extinctions

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News' newsletter.

Mac Oliveau

Science & Technology Writer

Mac Oliveau is a Los Angeles–based science and technology journalist for The Brighter Side of News, an online publication focused on uplifting, transformative stories from around the globe. Passionate about spotlighting groundbreaking discoveries and innovations, Mac covers a broad spectrum of topics—from medical breakthroughs and artificial intelligence to green tech and archeology. With a talent for making complex science clear and compelling, they connect readers to the advancements shaping a brighter, more hopeful future.